40 years of excellence

Darwin T. Turner made his mark by becoming the University of Cincinnati's youngest degree earner. His legacy lives on through the Turner Scholars Program.

When Darwin T. Turner was a student at the University of Cincinnati in the 1940s, diversity and inclusion were decidedly not priorities for the institution. That’s what makes his story even more remarkable: During a time when water fountains and bathrooms were still segregated by race, it was a black man who claimed the distinction of becoming the youngest person to ever earn a degree at UC, a record that remains unbroken to this day.

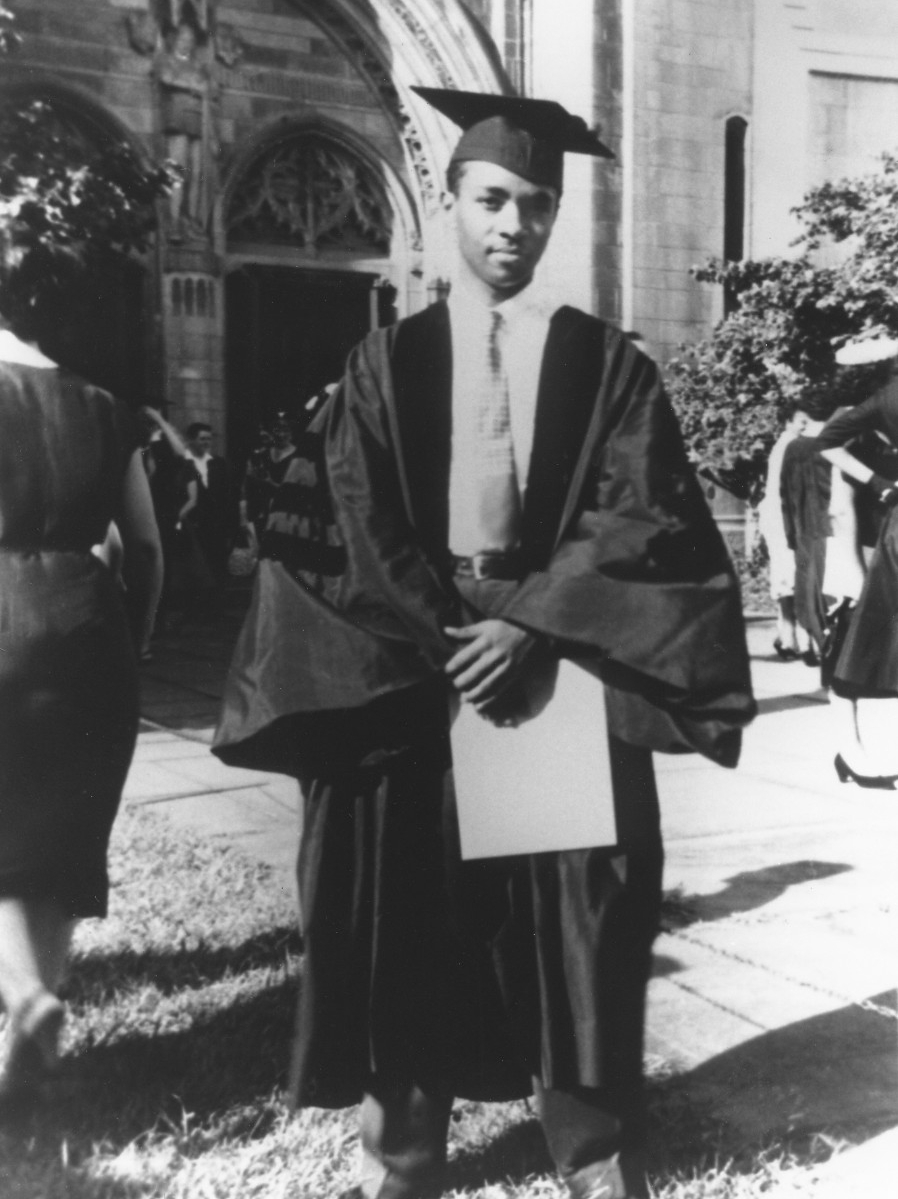

Turner was 16 when he earned his bachelor’s degree in English, a feat that only took him three years to accomplish. It took just two more for him to earn his master’s degree at UC when he was 18. After earning his doctorate at the University of Chicago, Turner went on to become one of the country’s most prolific critics of and foremost experts on African-American literature. He wrote or edited more than 20 books and countless articles. And though his life was cut short by a sudden illness at the age of 59 in 1991, Turner’s legacy carries on today in the scholarship program that bears his name.

The Darwin T. Turner Scholars Program celebrates its 40th anniversary this year. Since its founding, what was known until 1991 as the Minority Scholars Program has awarded opportunities to thousands of students of color that might not have otherwise been able to attend college. Being a Turner Scholar means more than just a tuition scholarship through college. It means being a part of something much, much bigger than one’s self.

Maya Angelou, right, applauds Jean Turner at a dinner honoring her late husband, Darwin T. Turner, on Oct. 12, 1991. The Minority Scholars Program's name was officially changed to the Darwin T. Turner Scholars Program that evening. Angelou was the keynote speaker at the event.

To Brandi Elliott, it meant discovering a part of herself that she had never had the chance to explore before. Elliott attended the now-defunct Landmark Baptist in a Cincinnati suburb for high school, where she jokes that she was the diversity in her class. She calls the day that her father handed her an application for the Turner Scholars Program the day her life changed.

Before the beginning of her freshman year in 1997, Elliott attended UC’s Black Student Welcome. She can recall being overwhelmed by all of the different organizations offering information and all of the different offices that were represented. But what she remembers most was a fiery call to action bellowed by P. Eric Abercrumbie, then director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services and the African American Cultural and Resource Center. Two decades haven’t eroded the memory’s vividness.

“‘You have a debt to pay!’” Elliott can recall him shouting. “He said, basically, that we’re here based on the blood and sweat of our ancestors. He said, ‘Don’t come to this predominantly white institution and not take any classes to understand your identity, to understand who you are.’ And he yelled it.”

Elliott and her fellow Turner Scholars were indebted to their parents, as well as figures like Abercrumbie, LaShanta Jones Tinner and Bleuzette Marshall, all of whom held leadership positions in the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services at one time. But there were others that came before them.

There were people like Odessa Walker Hooker, who attended UC in the 1960s when there was no Minority Scholars Program nor anything else in place to ensure that she and people who looked like her would feel welcome and accepted. It’s hard not to blame Walker Hooker for the half-century grudge she carried in her heart against her alma mater; the ugly ignorance of the day, even two decades after Turner achieved his unparalleled feat, made her pursuit of a master’s degree in education one of the most painful experiences of her life.

A married mother of four young children, Walker Hooker and her husband owned just one car. He took it to work, which meant she had to use the bus to get around, including to a Saturday class she learned to dread because of a cruel professor. “I had two options: I could get the bus and get there 30 minutes early, or I could get the bus and get there 5 minutes late,” she recalls. “I chose the latter because I had to do what I could for the children before I left home.

“He made comments that were very overt, racist comments to the whole class. He was not the only one, but he’s the one that I remember most vividly. He would say, ‘Some people just don’t know what it means to come to class on time.’ He would say that he didn’t believe that African-Americans — he didn’t call us African-Americans — but he didn’t believe that we could get a grade higher than a C. And he commented every time I came in late, because I came in late on Saturdays.”

Brandi Elliott, a former Turner Scholar, now runs the program in her role as the director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services.

UC Vice President for Equity and Inclusion Bleuzette Marshall is a past director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services.

“I grew with Turner. I think, by my second year, I already felt like a senior. In one year, I felt like I had already done so much with Turner.”

- Laura Mendez Ortiz, Turner Scholar and Mentor

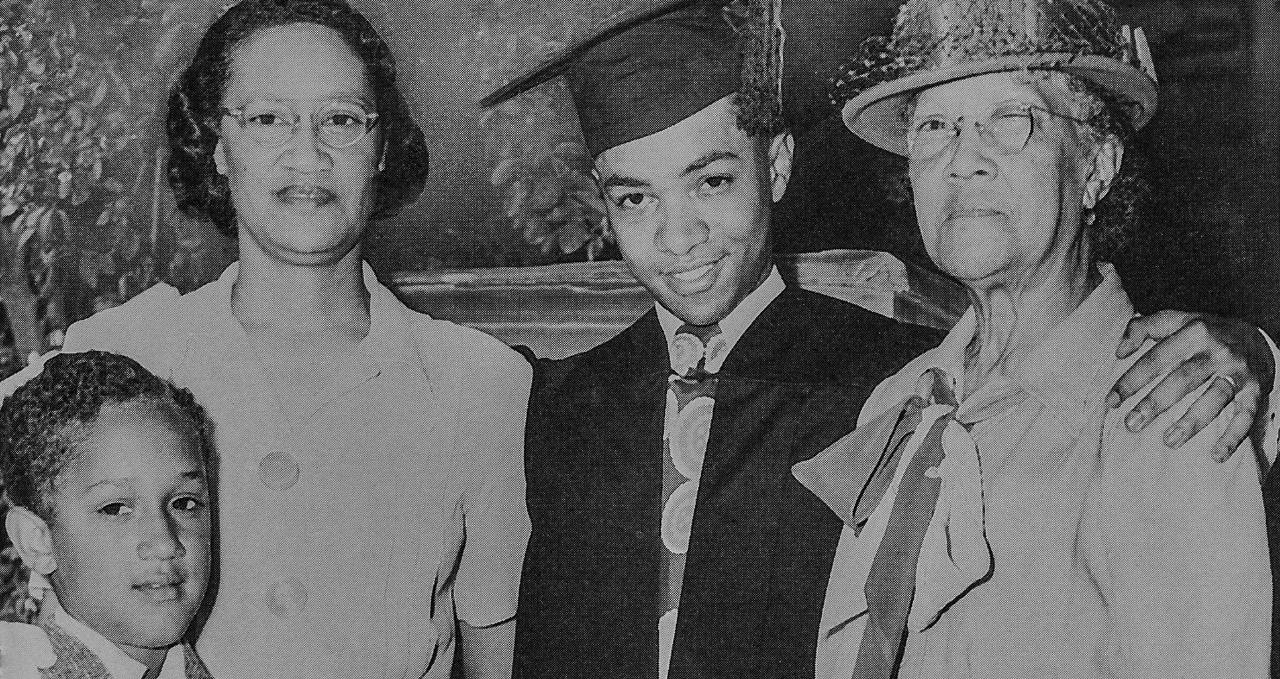

Darwin T. Turner graduated from the University of Cincinnati in 1947 with a bachelor's degree in English when he was 16 years old, and earned his master's degree from UC when he was 18. He remains the youngest person to ever earn a degree at UC.

As promised, Walker Hooker was given a C grade, the only one she received during her time as a UC student. But despite enduring abuse from that professor and two others, along with neglect from an unhelpful guidance counselor, Walker Hooker graduated with her master’s degree in 1967. She donated $25 per year to the alumni association — never a penny more or less — until the Turner Scholars Program became an option. Then she instructed her donation go toward the scholarship. “It was the only one I could feel good about,” she says.

Donations to the Turner Scholars Program created opportunities for more minority students to come to UC and still do to this day. Once a race-based scholarship, Turner is now open to students of all races, with preference given to students who demonstrate a commitment to diversity, students from underrepresented races and cultures and first-generation students.

They’re students like Laura Mendez Ortiz, a native of Bógota, Colombia, who immigrated to the United States with her family when she was 4 years old. Searching for a college as a senior at a Cincinnati high school, Mendez Ortiz wasn’t sure if there was a place for her anywhere. She would be a first-generation college student, so her search had her looking far and wide. She was nervous and rudderless, not certain where she would fit in. “I remember there was this one night at like two in the morning, looking up scholarship after scholarship,” she recalls. “Finally, I found Turner. It was like, in a hot moment, ‘That’s where I want to be.’”

Now a junior majoring in international affairs and environmental studies, Mendez Ortiz credits the Turner Scholars Program not only with helping her make it to college, but helping find a place where she belongs. “I grew with Turner,” she says. “I think, by my second year, I already felt like a senior. In one year, I felt like I had already done so much with Turner.”

They’re students like Madeline Mason, a Middle Eastern-American from the Appalachian town of Zanesville, Ohio. With a cousin who was already in the Turner Scholars Program, Mason knew exactly where she belonged, where the culture of diversity she craved could be found. When she visited campus for the first time, she fell in love with UC’s beautiful architecture and expansive green spaces. But when she arrived for her freshman year, she found that Turner isn’t just a scholarship program. It’s a family.

That’s something that Mason needed early in her collegiate career. She quickly found herself overwhelmed as she struggled with her classwork, which led to a struggle with depression. Her fall semester grades were below the standards required to keep her scholarship. But through the support of her parents, her Turner student mentor and the staff of Ethnic Programs and Services, she was able to find her academic footing. “Whenever I’m sad, whenever I need help, anything like that, I go to Turner first,” says Mason. “It just gets really overwhelming sometimes. Even when you’re trying to make decisions for yourself and you’re trying to be an adult, sometimes you need other people.”

Turner Scholar Madeline Mason

Turner Scholar Laura Mendez Ortiz

Mason spent the next four years paying it forward. She served as a Turner Ambassador, the program’s student leadership branch. She was a Turner Mentor to several students; to some, she was assigned, while she adopted others. She established Scholars for Ashley, a fundraising program that supports the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society and named for a childhood friend Mason lost to cancer when she was 14. Now about to graduate from the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning with a degree in fashion design, Mason hopes to someday be able to support the Turner Scholars Program as much as it supported her. “I don’t know if any of the things I have done would be possible without Turner,” Mason says.

They’re graduates like Elliott, who went on to earn her bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees at UC. Elliott can remember when Ethnic Programs and Services was located in Tangeman University Center before its renovation in the early 2000s. She recalls meeting up with fellow students there at lunchtime every day to watch “The Young and the Restless.” She can remember sitting on the floor of Jones Tinner’s office, venting her frustrations and sharing her fears when things got tough. She remembers the tough-minded encouragement she received during those meetings. “I loved it, because it was in-your-face direct,” says Elliott. “You didn’t have time to sit on the floor and cry.”

Now Elliott is the director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services and leads the Turner Scholars Program. She’s the one doling out tough love to students who sit on the floor of her office and share their frustrations. She gives them the same message that Jones Tinner, Abercrumbie and Marshall gave her when she needed to hear it: “I’m gonna give you this minute. But get up. Here’s a tissue. Let’s get to work. You got this.”

Director of Diversity Eric Abercrumbie, left, formerly served as the Director of the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services, as well as the African American Cultural and Resource Center. Abercrumbie was at the helm of Ethnic Programs and Services when the Minority Scholars Program was renamed to honor Darwin T. Turner.

Between her days as a student and now as a member of UC’s staff, this is Elliott’s 20th year of involvement with the Turner Scholars Program. She knows what today’s students must feel when they learn they’ve been accepted to Turner. She’s been there, and she has a better idea than anyone what the future might hold for them. She knows how important it is for students to have the support system and network Turner provides. It’s her responsibility to make sure today’s Turner Scholars get the same support she got all those years ago — a responsibility she never takes for granted.

“It’s humbling,” says Elliott. “I thank God every day for this opportunity to be at this institution, to be in this office and run a program as dynamic as the Darwin T. Turner Scholars program. I’m happy to celebrate 40 years of excellence — 40 years of scholarship, service and success.”

Under Elliott’s leadership, Turner continues to evolve. Just this year, the Turner Scholarship became available to students from outside of Ohio for the first time. Elliott envisions the program continuing to grow. She sees the Office of Ethnic Programs and Services soon outgrowing its current location at the Steger Student Life Center. She believes that the program will continue to receive more funding, and predicts that more students will have the chance to earn full scholarships. Continuing the push for diversity and support for students from underrepresented backgrounds are as important now as ever, she said.

“We can’t forget that there are other students out there who need support,” Elliott says. “There are students out there that don’t know what’s going to happen to them or their families tomorrow. There are students that get profiled just based on what their name is. We pay attention to that.”

A gala celebrating the 40th anniversary of the Darwin T. Turner Scholars Program will be held Saturday, April 22, from 6 to 9 p.m. in the Great Hall at Tangeman University Center. Tickets can be purchased on the University of Cincinnati Foundation website.