Eric Abercrumbie at the AACRC's annual Tyehimba event. Photo/AACRC

This week, 25 years ago, the AACRC opened its doors

For a quarter century, the African American Cultural and Resource Center has broken barriers, empowered students and sought to end the ‘polite silence on race.’

by Jessica Noll

513-556-1823

Sept. 29, 2016

What is it like to be a black college student?

It’s a tough question that encompasses so much that it’s nearly impossible to answer in one sitting. But Ewaniki Moore-Hawkins, University of Cincinnati’s African American Cultural and Resource Center (AACRC) director, makes the attempt.

“The beauty and the difficulty of being black in America and abroad is something that people dedicate their entire lives to unpacking and explaining. It is a lived experience. What I can say is that being black in America, knowing the accomplishments and hardships that underline our history, has given me much appreciation for my culture, my freedom and my education. However, it also embodies a wealth of challenges,” she says.

While navigating through the various obstacles as a black woman, Moore-Hawkins says she has been challenged in ways that her peers and colleagues have not, but she’s also grown in terms of perseverance, fortitude and determination.

Engendering just those kinds of qualities is why the AACRC was formed on UC’s campus 25 years ago. And this week, the center is celebrating more than two decades of service as a home away from home for black students, as well as its role as a space of inclusion to all on campus and in the community.

Given the name, it’s assumed that the center is only for African American students, but Moore-Hawkins says the space is all-inclusive. In fact, she says a lot of groups come to learn about the black experience and what it’s like to be black in America, specifically on UC’s campus.

The AACRC was, indeed, initially established to assist students of color, specifically black students, with matriculation through the university toward graduation. In addition, the center provides an environment that helps black students thrive, embrace the university and have a sense of place, says Moore-Hawkins. She began serving as director in 2013, after filling roles as program coordinator and the assistant director to then-director Eric Abercrumbie.

Being a black student on campus herself, beginning in 1997, was a social and environmental adjustment for Moore-Hawkins, and she understands the need to have a home base.

Ewaniki Moore-Hawkins, AACRC director

“I witnessed various injustices in and out of the classroom, which influenced me to get involved in various organizations and service groups,” she says. “I, like many other black students, then and now, did not see myself represented or even valued in various aspects of UC's community.” With the support of the AACRC, she was better able to face the challenges of being a black student at a predominately white institution. Moore-Hawkins served as a resident advisor, the center’s first “Miss Kuamka” and as “Executive of the Year” in Advance, an African American professional development student organization.

Some of those challenges, she says, included having her needs or concerns overlooked, having assumptions made about her abilities or her background, or having to work twice as hard to prove herself in order to get the same opportunities as others.

“I utilized these challenges to grow and groom my path to becoming a positive black woman role model to today’s black students.”

Once a first-generation college student, Nicole Ausmer, director of Student Activities and Leadership Development, agrees.

“The AACRC supported me on my identity journey and taught me that ‘black is beautiful,’” she says of the staff who became her family and of the center that became her home. “They valued my ideas and encouraged my activism.”

While neither Ausmer's mother, grandmother nor great-grandmother completed high school, Ausmer has herself achieved three UC degrees — earning her bachelor’s degree in 2005, her master’s in 2006 and her doctorate in 2009.

Nearly 50 years in the making: How the center came to be an invaluable resource

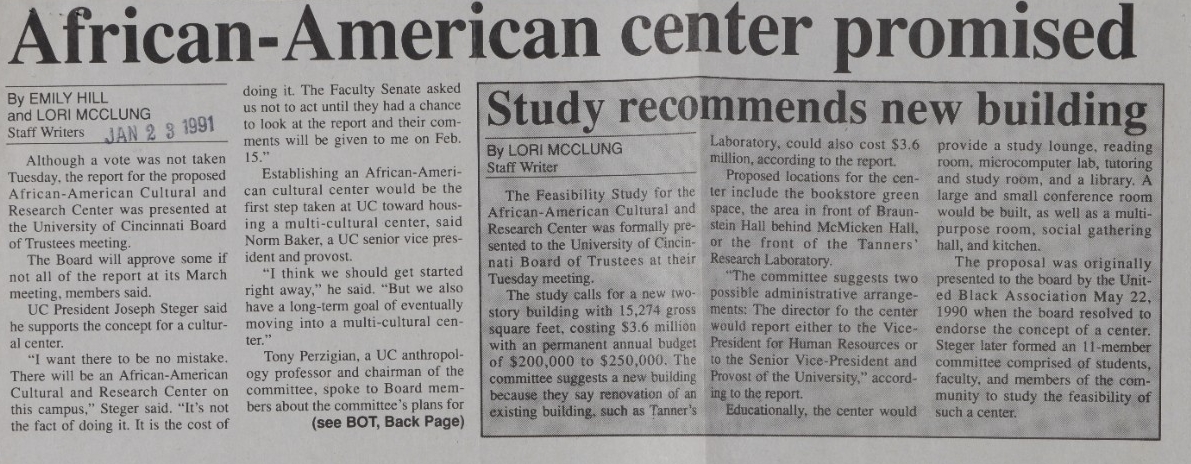

According to the AACRC’s historical timeline, in 1968, the United Black Association (now called the United Black Student Association) led a student protest that issued a list of 30 demands to then President Walter Langsam regarding racial discrimination and inequalities on campus.

Those concerns included a lack of black faculty and staff, as well as little to no support for African American student organizations on campus.

Several demands were met including the establishment of the African American Studies Department, the recognition and funding of the United Black Association as well as the promise of a black cultural center.

It would be nearly 25 years before some of those efforts would come to fruition.

Beginning his journey at UC in 1972, Abercrumbie dubs himself as the 'original diversity liaison.'

“Our offices were trying to get people to understand cultural and racial differences when nobody was doing it here. I’m the one who started doing black programming on this campus — having culturally conscious conversations,” he states.

The former AACRC director (1991-2003) said his involvement to bring a black cultural center to campus occurred when he took students on an annual spring break tour (now a staple outing for the AACRC). One stop on that tour changed everything.

Abercrumbie recalls, “We stopped at Vanderbilt University in [1988] — and they were like, ‘OK, we want this at UC.’”

Student Harlan Jackson and the United Black Student Association really took the initiative after visiting the Joseph Bishop Black Cultural Center at Vanderbilt University.

When they returned from the spring break trip, the group of students approached Student Government, the university Board of Trustees, Faculty Senate and administrators asking, 'Will you be supportive of a black culture group?'

The students also went to Dr. O’dell Owens, then on the UC Board of Trustees, and said they’d like to have a black cultural center. Eventually, Owens and his wife donated approximately $10,000 to further the center, recalls Abercrumbie, who is now the executive director of diversity and community relations in the university’s Division of Student Affairs.

But it was still a long road. The center had to go through several phases of research and review as part of UC’s governing process.

Former UC President Joseph Steger supported the idea, as did the Faculty Senate and the UC Board of Trustees. During the board vote of spring 1991, student Jackson presented a collage of racist incidents experienced by black students over the previous 20 years.

“I’ll never forget one of the Faculty Senate members, when they took the vote, saying, ‘Obviously, in all this time, we haven’t been able to do the things that need to be done. We’ve got to try something,’” Abercrumbie vividly remembers. That vote was instrumental. Without the Faculty Senate vote, there would be no black cultural center.

“When that vote happened, it was a glorious time,” he says.

After board approval, a committee formed to research cultural centers and travel the country to visit similar facilities. With research in hand, they submitted a proposal to the administration detailing a freestanding black cultural center at UC.

“[Steger] said that the center was a promise or a gift for all the oppression and racial injustice that had happened to black students throughout UC’s time,” says Moore-Hawkins who, at that time, was in sixth grade. "He promised that he would help create something that would alleviate that.”

After all of the hard work, determination and perseverance, the day of the center’s opening finally came on Sept. 24, 1991.

The African American Cultural and Research Center was born. The name was later changed to the African American Cultural and Resource Center, as it was a better description for their goals, says Abercrumbie.

“The day we went into the cultural center was historic,” he recalls. And he believed that the first people to step through the door for the dedication should be some of the university’s trailblazers, like Georgia Beasley, who graduated in 1925.

“I think those black students who came here and faced the systematic oppression that they faced and still were able to achieve in spite of it… would be proud [of the center],” claims Abercrumbie, who added that at her Commencement, Beasley was told to stand in the back. At which point, she replied, “I refuse to walk by myself.”

Abercrumbie explains that the opening of the center reflects how diversity and inclusion really work: "...here were black students saying they still don't feel a part. This center would help us feel like more of a part of the campus.”

At the time, there were some who believed the cultural center would promote segregation on campus. This, however, has not been the case, according to Abercrumbie, who points out the entire campus community – representing all races – uses the center.

“That was one thing we made clear. The center is a black center in focus…but it’s not just for black people. And that’s what I really love about the center. I feel that we’ve carried that mandate out as far as who uses the center,” he says. “It’s places like the cultural center that cause people to come together. It’s just the opposite [of segregation].”

“The center means that the university community had the awareness and sensitivity to understand the historical oppression that black students and people from the community have experienced at the University of Cincinnati and had decided to do something to correct those injustices and insensitivities.”

The history of UC, like that of other institutions in society, includes well-documented segregation, where many black students were routinely excluded from full participation in campus life, whether academically or socially.

“The reality of the historical injustices and the historical racism that has happened on this campus has caused generations of people to hate this place,” says Abercrumbie. “So something like the cultural center comes along, is a testimony, in many ways, to say, ‘We’re sorry. We understand why you feel the way you do, and we don’t want you to experience what your grandparents and great-grandparents experienced.’”

And to anyone who thinks the university doesn’t care about black students or helping them to be successful, Abercrumbie says, the cultural center is that statement that UC does.

“The AACRC is an invaluable resource for students of color,” says UC grad Antwone Cameron, assistant dean of student affairs at Thomas More College. “It gave me a sense of belonging and a comfortable place that I could call home. It was a restorative place that gave [me] knowledge and strength to leave my mark…in positive ways and encourage other black students along the way,” continues the 2015 graduate, who earned both his master’s and bachelor’s degrees at UC.

Mario Jovan Shaw, CEO of Profound Gentlemen and a 2012 UC graduate, agrees.

“The center is and forever will be known to me as an incubator space for those who seek to find their purpose and desire to create change.”

UC celebrates not only black students, but also black educators and achievers.

For example, the Edwards Center on UC’s campus is unique because it was named after Vera Edwards, a black woman and an educator, who was still living at the time of its dedication. She was the third black woman to ever earn a master's degree at UC.

“You don’t get a building named after you unless you give big money, or you’re dead. This was a black woman who was an educator [honored at UC],” says Abercrumbie, who also points out the statue near Fifth Third Arena of basketball player Oscar Robertson. “Maybe the best basketball player to live.”

Turner Hall is named for an African American. It's named after the youngest baccalaureate graduate ever from UC, Darwin Turner, who graduated in 1947 at 16 years old.

There aren’t many schools that can landmark one thing for black history on campus, he says, yet UC has these four “statements,” including the center itself: “I think those black students who came here and faced the systematic oppression that they faced and still were able to achieve in spite of it…would be proud.”

“The black cultural center allows black history at the University of Cincinnati not to be lost anymore…not to be hidden. It allows us to be able to navigate into the future when we look down the road. There’ll be black students who come here who won’t have to say, like their great-grandparents and students before them, ‘I don’t feel welcomed today at that place,’” according to Abercrumbie.

These days, UC students can frequent the AACRC and not only meet with staff but also connect with other students, as well as the larger community. The AACRC is a space that can be reserved for student organizations, as well as groups throughout the community. Most days the center is full, hosting campus gatherings or events. Last school year, the AACRC welcomed more than 400 events and 19,000 people.

“It’s a great hub of activity and [has] a great energy around [it],” says Moore-Hawkins, who started at UC just after graduating from Walnut Hills High School.

“As soon as I came, I instantly was looking for something to connect with and found the cultural center, and it literally became my home away from home — especially since I was a commuter student,” recalls Moore-Hawkins, who would go on to join the AACRC Choir and choir president.

“It was great to be a student because that gives me a unique perspective to know what it’s like to be a student at the center.”

And now, she’s making her mark on the center.

She started looking at programming that would attract the black graduate student population and transfer students. She also created a new leadership role called the “Habari Gani Ambassadors,” in which about 15 students serve as an extension of center staff and represent it across campus, as well as help develop programs. They learn to lead, speak, work with social media and photography — whatever their interest is — and use it to represent the center and its mission.

Abercrumbie, she says, laid the foundation, and under his leadership, the AACRC developed its choir and its signature programs. Many are models for universities across the United States.

One such program is Tyehimba, a celebration designed to acknowledge the achievements of UC graduates. “The [Tyehimba] is the best in the country. Other universities have come here to study it,” says Moore-Hawkins.

AACRC's annual Tyehimba event is a cultural celebration expressing thanks to family, friends and the community. The word "Tyehimba" means "we stand as a nation." Photo/AACRC

Signature programs

Akwaaba — The fall-term black student welcome is designed to be informative and serve as an introduction to campus services and student organizations in an effort to keep students connected throughout the school year.

AACRC Choir — Choir cultivates the talents of young, gifted and black students who come together for one common purpose: to inspire the lives of others through song. Students who are selected to participate in the choir are exposed to various types of African and other culturally based music.

BASE — Brothers and Sisters Excelling is a peer-mentoring and role-modeling program designed to aid in the personal, cultural and educational development and retention of black students during their matriculation through UC.

Brother 2 Brother — This program focuses on issues that affect the matriculation, graduation and overall success of black men. As part of the program, students, faculty and staff come together to discuss critical issues and provide each other with necessary support and guidance.

Habari Gani Ambassadors — The role of a Habari Gani Ambassador is extremely important and vital to the success of the AACRC. Each ambassador serves as a driving force to advertise and assist with many events and initiatives of the center.

Kuamka — Swahili term for "in the beginning"- is a weeklong celebration which includes the rites of passage ceremony for Transitions students, the coronation of “Mr. and Miss Kuamka” and the recognition of students who have excelled academically (or Kujifunza). Mr. and Miss Kuamka represent the AACRC for the subsequent year.

Kuamka is a weeklong celebration which includes the coronation of “Mr. and Miss Kuamka," who then represent the AACRC for the year. Photo/AACRC

Martin Luther King Jr. Tribute — The MLK Tribute highlights the contributions of Martin Luther King, Jr., made to change the course of history for African-Americans and mainstream society. This program is designed to be creative, informative and inspiring for students and the UC community.

Sisters Impacting Sisters — This is a program in which black college women can honestly engage in dialogue and work through issues concerning their roles in the university community and society. SIS focuses on relationship building, personal development and community service.

Spring Break Tour —This tour has two travel routes and gives students the opportunity to explore various cities, engage with alumni and network with college students throughout the South. It’s also the trip that started the journey to obtaining the AACRC for UC’s campus.

Transitions — Transitions is a first-year experience program connecting students to faculty, staff, alumni and peer mentors. The ultimate goal is to increase the retention and graduation rates for African-American students at UC.

Tyehimba — This cultural celebration is an expression of thanks to family, friends and the community for their assistance and support to graduating students. The word "Tyehimba" means "we stand as a nation."

Ushindi — Ushindi, which is Swahili for "victory," takes place toward the end of the academic school year. Ushindi celebrates the achievements of the students from the Transitions program, the AACRC Choir and also recognizes other students who have demonstrated leadership on and off campus.

UC's annual Tyehimba graduation celebration serves to mark the success of students while also serving as an expression of thanks to family, friends and the community for their support of graduates in the achievement of their degrees. The word 'Tyehimba' means 'We stand as a nation.' Photo/AACRC

The annual tour that jump started the engine for the AACRC is now a tradition. It takes 40 students on a trip throughout the South. Similar to a social justice tour, students visit historical sites and other universities and can talk to peers to understand what their experience might be like on those campuses, says Moore-Hawkins.

They travel to both predominantly white campuses as well as Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU).

While they were once inspired by other universities’ cultural centers, UC’s AACRC is now known as one of the most active centers nationwide for the work they do, including breaking the silence.

“The cultural center helps break the polite silence on race that exists on many campuses,” says Abercrumbie.

If you want to go someplace safe, where you can hear what students really think about things like the Sam DuBose shooting, he says, the cultural center should be one of those places. If for no other reason, the center allows everyone to come together, sit at the same table and not feel apprehensive about asking anything — and being comfortable giving those answers truthfully, he adds.

“Most of the students and staff who come to the University of Cincinnati really miss out if they don’t take advantage of our diversity. That is why diversity is something we can always hang our hat on as being important and as being something that we’re striving to improve,” according to Abercrumbie.

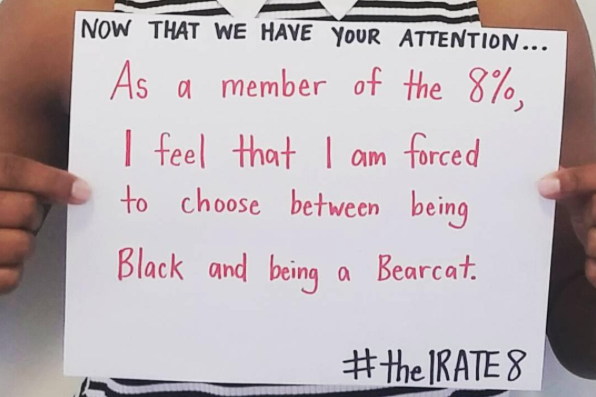

Creating leaders, making a difference, demanding change: #theIrate8

Encouraging student leadership is integral to the AACRC’s mission.

In fact, UC has had eight black student body presidents, and many of them were cultural center students, starting in 1973 when Tyrone Yates, class of 1978, was elected as the first black student body president.

In the center, students have a voice, Abercrumbie contends. It’s a place to have a conversation. He knew that the center would connect the students more with the university, and in turn, connect the university more with them.

When tragedy struck the UC community in 2015, the center’s students raised their voices.

“Once the Sam DuBose shooting happened, those students got together and said, ‘OK, what are we going to do about this?’” remembers Moore-Hawkins.

Students within the center, she says, are conditioned to react to adverse situations on a different level than those black students not involved with AACRC.

“They understand how to use their status as students to move the needle or make an impact,” she says. “These aren’t the kind of students who just sit and complain about it. They go to action and figure out what they can do to make things better.

“And that’s mainly because, with the center, they are embraced here and throughout our programming. They learn how to be active and how to make things better. We teach them it's about what legacy are you going to leave? It’s not good enough for you to just come here as a student, get your degree and go. How are you going to make sure that this institution is better when you leave? And we tell them that coming in the door.”

Because of that, when systematic oppression arises, those students, she says, are trained to instantly say, “OK, what are we going to do about it?”

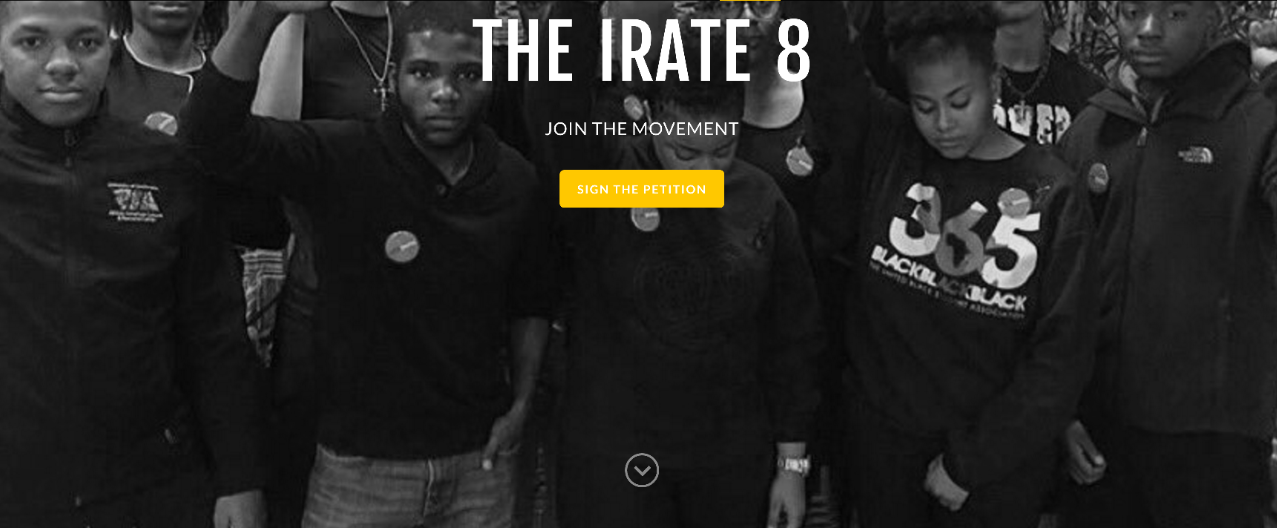

That’s how the group the Irate 8 was born, organizers say, carrying on the traditions that helped found the AACRC— to create leaders, make a difference — and leave it better than how you found it.

“The cultural center [is] a place that allows students…who might be angry, to be able to assemble and come together and work through volatile issues,” says Abercrumbie.

Ashley Nkadi is one of the co-founders of the Irate 8. A 2016 UC graduate with a bachelor’s degree in neuroscience, the 21-year-old is now pursuing her master’s degree. But it wasn’t long ago that she was leading the cause that reached millions via social media.

“Our initial goal was to respond as a black community to the July 19 [2015] incident and express our frustration with the inadequate response as well as identify what this incident was a larger indicator of at the university…a movement that pressed the university to ramp up inclusion and equality in all facets of campus life,” says Nkadi.

#theIRATE8

Ashley Nkadi, co-founder of the Irate 8

Shortly after DuBose was shot and killed by a former UC police officer, some of the older members of the Lambda Society, a black women's honorary, began asking the active members what they would do and how they would respond. Irate 8 co-founder Brittany Bibb, now a UC academic adviser, called a meeting where representatives from all of the black student organizations came to listen, speak and pitch ideas. In that meeting they came up with the group's name, mission, purpose and the preliminary demands of the group.

The Irate 8 was a student movement fueled by social media.

With social media, they mobilized students and the community, looking at the situation as one issue that sparked an examination of other inequities for black students that required change, says Moore-Hawkins.

They compiled a list of 10 demands for the university. With the list, the group also created programming to address the issues. The programs included workshops and panels on policing in an effort to educate the university community, while also challenging the university and community on the need for institutional change.

The group held several meetings with then President Santa Ono and other leaders to discuss their demands. From that, UC leaders deployed committees to examine these concerns.

The results of these cooperative efforts include an expansion of the AACRC, based on committee recommendations. Renovations began this summer to add a kitchenette and two more rooms, one a quiet study space and one for a student lounge, as well as increased storage and updates to the restrooms.

States Abercrumbie, “Every time we improve [the center], we improve the campus atmosphere.”

“There [has] been movement and progress on many of the demands,” says Moore-Hawkins.

And Nkadi points to many changes besides the expansion of the AACRC. These include a program that will admit more more students from the Cincinnati Public Schools through an ambassador program, improved transparency and student input into university police and public safety, student roles in the hiring of more diverse faculty, and a mandatory comprehensive racial justice course for students and student organizations.

Student, Faculty and Staff Partnerships with the President and Provost

https://uc.edu/inclusion/latest/presidentprovostpartnerships.html

Partnerships with UC’s Vice President for Equity and Inclusion

https://uc.edu/inclusion/latest/CDOpartnerships.html

UCPD Safety and Reform

https://uc.edu/inclusion/latest/UCPDupdate.html

The Irate 8 actions became a blueprint for other student-run, campus movements including the University of Missouri, where students used a copy of the Irate 8’s demands to challenge their own school.

“We are here. We will always hold the university accountable,” says Nkadi. “It is never too late, too uncomfortable or too disruptive to make lemonade out of lemons.”

The movement was transformational for all phases of campus life, she says. The university began to look at diversity more closely as a whole and not just for the sake of appearances but in order to make actual lasting change.

“Our movement was studied and analyzed in a ton of classes at UC. We collaborated with other activist movements. Organizations at UC began to support us by posting our demands and letters of support, and there was [a] petition of support that hundreds of faculty signed. It was amazing,” adds Nkadi.

If it wasn’t for being a part of the AACRC, Nkadi might never have helped form the Irate 8. Through the center, she says, she learned how to lead an organization, how to use social media and how to mentor other students to develop them in playing a role in the movement.

The AACRC also allowed her to get in touch with her roots and embrace her community.

“It taught me you must lift as you climb. It taught me how to embrace my blackness,” says Nkadi. “It taught me how to love myself and be myself. It showed me to not only nurture and develop our own community, but to take my talents outside of its walls to be a representative of black excellence and black success.”

Photo/AACRC

More black graduates than ever

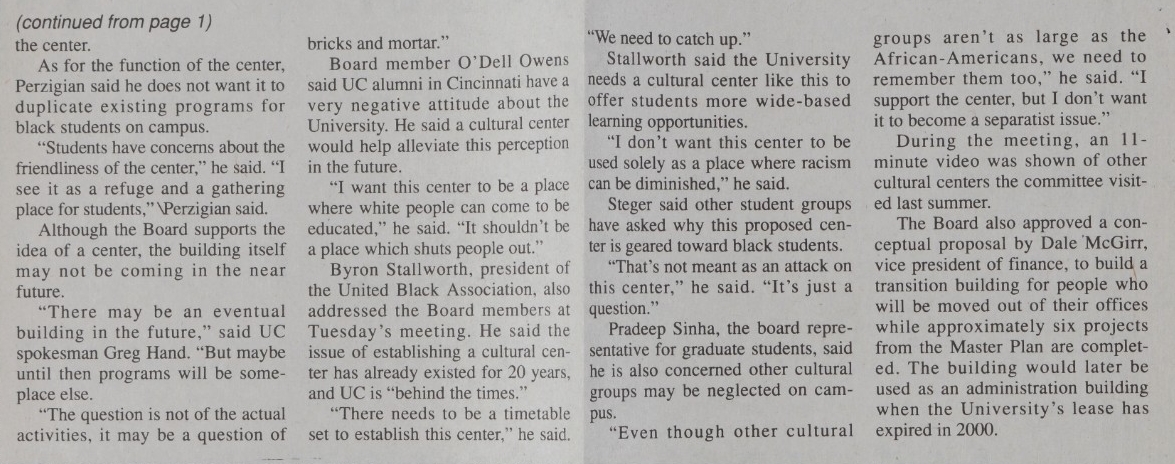

The “8” in the name Irate 8 is the percentage of UC’s student population that is African American, a drop since Moore-Hawkins was a student, which is one of their concerns, she says.

However, retention and graduation rates for African-American students have improved markedly over the past decade. Ten years ago, the first-year, full-time baccalaureate retention rate for African American students stood at 70.5 percent. Today, it stands at 87.1 percent.

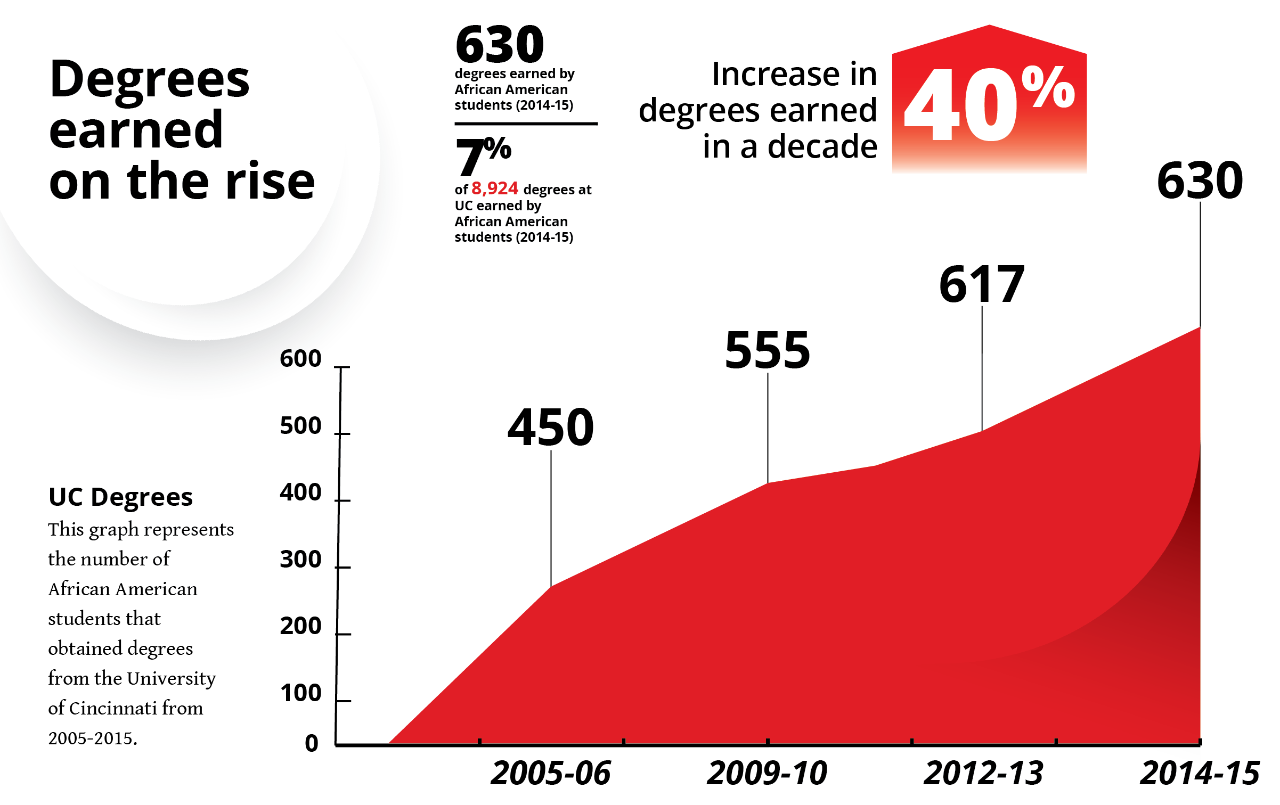

And the number of graduate and undergraduate degrees combined, earned by African American students in the past decade, has jumped by 40 percent, according to UC’s Office of Institutional Research.

The AACRC has had its role to play in these rising numbers. States Abercrumbie, “The cultural center has been a staple of implementing Bearcat pride in students who have historically not had pride in being where they are.” He continues that the center increases the university’s appeal. There are people who opt to send their child to a university when they see there is a black cultural center, he says.