NFL concussions get attention from UC alumni experts who consult with the Cincinnati Bengals following a head injury

by Melanie Titanic-Schefft

Media contact: John Bach, 513-556-5224

Published October 2014

September 2018

September 2018

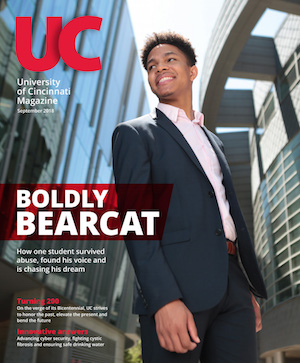

Boldly Bearcat

Finding his voice

Danger in the tap

Virtual defense

Global game changer

Celebrating UC's Bicentennial

Past Issues

Past IssuesBrowse our archive of UC Magazine past issues.

Media contact: John Bach, 513-556-5224

Published October 2014

A perfect spiral sails downfield as a wide receiver cuts across the middle, plucks the pass out of the air and plants his feet to prepare for impact.

The first-down catch draws a deafening roar from the home-team crowd that is quickly followed by an eerie silence as he is leveled by a helmet-to-helmet blindside hit courtesy of a 245-pound linebacker.

The sounds of Sunday reverberate in NFL stadiums around the country this time of year, but in a climate where concussion lawsuits are common and concern over sports-related brain injuries has never been higher, no sound may be more vital than that of the team’s Monday-morning phone call to their concussion experts.

For the Cincinnati Bengals, those calls are answered by two of UC’s distinguished alumni. Neuropsychologists Tom Sullivan, M (A&S) ’91, D (A&S) ’94, and Wes Houston, M (A&S) ’95, D (A&S) ’01, are brain-function experts who evaluate a player for a possible concussion and advise how best to treat or how long to rest before his brain has healed and he can suit up again.

A UC researcher is helping the Bearcats take the concussion conundrum head-on, and the results are turning heads.

While fans and the media are far more concerned with a team’s on-the-field talent, management, coaches and even players understand it’s often the talent that they retain behind the scenes that really sets them apart.

“We value Drs. Sullivan and Houston tremendously,” says Paul Sparling, head certified athletic trainer for the Bengals. “We trust them and listen to their advice closely when it concerns questions of head injuries. We won’t let a concussed player back into play until they have been cleared by Sullivan and Houston.”

In addition, the Bengals seek the OK of a league-mandated independent neurologist, a role also filled by UC graduates in Brett Kissela, M (Med) ’09, director of neurology at UC College of Medicine, and William Knight, D (Med) '03, assistant professor of emergency medicine and neurosurgery. Both are also part of the UC Neuroscience Institute.

Long before the recent $870 million concussion lawsuit was brought against the NFL by thousands of former players, the Bengals had already stepped up their program to assure the health of their players through a concussion-management program that Sullivan helped implement in 1998.

New rules in the NFL have also dramatically increased requirements for training and medical staff to closely monitor players during games and weekly practices. Sullivan and Houston, as well as the team’s neurologists, evaluate all Bengals players who have suffered head injuries.

“There have been great strides made in the last few years in the NFL for traumatic brain injury prevention and treatment, and we have been using many of those methods with the Bengals,” says Sullivan. “While we are not mandated to be at every home game, we always evaluate players a few days after a concussion and perform serial evaluations until the player recovers and returns to play.”

Even before the Bengals donned their practice pads and geared up for training camp this season, all new players met with either Sullivan or Houston who performed neuropsychological baseline testing. Plus, they re-tested returning players who had suffered concussions last season.

“We do an individual, 30-minute battery of tests with each new player when they come onto the team,” says Sullivan. “Dr. Houston and I do baseline evaluations for orientation, somatic complaints, visual memory, verbal memory, mental processing speed and attention skills.”

The baseline scores for each of these tell the neuropsychologists and concussion management staff how the player functions on a normal basis. Retesting after a head injury then gives the staff valuable information about where, if any, the intracranial damage has occurred. All this helps to gauge what kind of treatment or how much rest is needed before the players are ready to get back on the field.

Neuropsychologists such as Sullivan and Houston know the intricacies involved with trauma to the sensitive brain regions and the tissue inflammation and bruising that can result. With their knowledge of the different functions of each cerebral area, and through intensive evaluation and testing, they can best appraise the damage and prescribe treatment for the most efficient healing.

When it comes to treating concussions effectively, rest is usually the key, Houston says, and sometimes avoiding bright lights and loud music. Most important is avoiding any further injury to the head during the healing process. While this can mean a player watches the next two or three games from the sidelines, the necessary time-out can make the difference between a temporary injury or long-lasting damage that can subsequently impact the length of a player’s career.

Working closely with the medical staff and training team and knowing the individual players intimately has been critical to Sullivan and Houston’s success.

“The secret to the Bengals’ superior concussion management program is that the players know and trust the doctors who provide them care,” says Sullivan. “It all comes down to a personal relationship and trust.

“We provide a clinical service to the players, and our work with the team is highly confidential. Our bottom line is making sure that the players are healthy and safe.”

In recent years, several professional sports teams have begun using computerized concussion testing systems. This may be a less labor-intensive and more cost-effective way of evaluating large groups of athletes, but Houston and Sullivan maintain it isn’t as effective.

“We always do an individual assessment of our players instead of computerized testing,” says Houston. “The behavioral observations you get from working with players in a face-to-face interaction are invaluable for knowing when and why a person is losing focus during testing, whether it be from post-concussion symptoms or because of distractions or loud noises in the training room. If they are not brought back into focus, this can skew their test scores."

Full-time careersTom Sullivan and Wes Houston learned the intricacies of neuropsychology –– the study of brain behavior relationships –– as graduate students in UC’s department of psychology. Sullivan studied neuropsychology at UC, learning neuroanatomy and neuropathology, then interned at the Yale University School of Medicine. Houston became one of the first graduates of UC’s formal neuropsychology graduate program. Both Sullivan and Houston continue to stay busy with full-time careers in addition to consulting with the Bengals. Houston is the director of the Cincinnati VA Medical Center neuropsychology department, which is part of the mental health program that staffs more than 50 psychologists, many of whom specialize in post traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and treatment. He consults with the PTSD and traumatic brain injury residential treatment program at the VA and also sees patients as a neuropsychological consultant at the Riverhills Neuroscience Institute on a part-time basis. Sullivan maintains an active private practice specializing in adult and pediatric neuropsychological evaluation, as well as forensics and legal consultation. He has served as an expert witness in criminal and civil cases in about 20 states. The U.S. Supreme Court has recently ruled that cognitively impaired people should not be executed, so Sullivan has also recently begun to evaluate prisoners on death row. Both Sullivan and Houston maintain their connection to UC by supervising students from the university’s clinical psychology doctoral program. |

One of the first concussion management programs was developed in 1995 by neuropsychologist Mark Lovell for the Pittsburgh Steelers. In 1997, Lovell became the first NFL director of neuropsychological testing and concussion management, and in 1998 the Bengals became the third team in the league to adopt the system.

“I learned how to evaluate football and hockey players with the battery of tests from Dr. Lovell,” said Sullivan. “I was already in consultation with the Bengals’ medical staff so they brought me in as an independent consultant for their concussion management program in 1998. I performed all their neuropsychological testing until 2010.”

Following the backlash of lawsuits against the NFL by former players with head injuries, Sullivan was hired by the NFL in 2010 to join a handful of other neuropsychologists to help formulate the battery of tests for the retired players involved in the lawsuit.

After two years, however, he returned to the Bengals and now co-directs the team’s concussion management with Houston.

Both doctors recognize how much concussion management in football and other sports has improved since the 1970s, explaining that head injuries are recognized quicker, and the treatment is much more effective. In addition, the technology has improved to not only better facilitate rehab, but also to train the players more effectively to minimize or avoid injuries altogether.

Sullivan even testified before the Ohio Legislature about concussion management legislation that was passed in 2012. According to the doctor, that bill mandates that youth coaches must now receive efficient training in concussion recognition and are made aware of the danger of leaving concussed athletes in a game.

Related article:

Bearcats train the eyes to save the brain

- Melanie Titanic-Schefft is a senior journalism student and writing intern with UC Magazine