A SpaceX Falcon rocket lifts off from Kennedy Space Center to deliver cargo to the International Space Station in 2017. (NASA)

This cat is ready to roar

UC CubeCats will launch its first satellite, LEOPARD, into space to help NASA study harmful radiation.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Lisa Britton/UC Creative Services

March 2, 2018

NASA intends to launch a satellite designed and built by University of Cincinnati students to study harmful radiation.

NASA informed the student club UC CubeCats on Friday that its cube-satellite proposal was selected for a future space mission with a launch as early as next year.

“I laughed and cried at the same time. Pure joy,” club founder and engineering student Adam Herrmann said of his reading the email from NASA.

Herrmann founded the UC CubeCats as a sophomore in 2015 when he learned that NASA was launching small, university-made satellites called cubesats into orbit around the Earth.

Cubesats are about the size of a Rubik’s cube. They share a mix of common and specialty components designed to accomplish specific missions. Most fly in low Earth orbit for a few months before burning up in the atmosphere like the world’s first satellite, Sputnik, did in 1958.

NASA picked 11 projects in its ninth round of the CubeSat Launch Initiative, which to date has launched 59 of the small satellites into orbit.

After celebrating the news with his CubeCats team, Herrmann called his mom.

“We’re going to build something that could help astronauts get to Mars or deep space,” Herrmann said. “For the first time in my life it feels like I’m contributing to something greater than myself.”

This week’s email from NASA was an announcement Herrmann has been anticipating since he first daydreamed about his own space missions three years ago.

“I was talking to a friend in our rocket club and threw out a crazy idea. Wouldn’t it be cool to launch a rocket into orbit? And wouldn’t it be cooler to launch one with a payload on board like a satellite?” Herrmann said. “My friend replied, ‘Yeah – like a cubesat.’”

Herrmann decided to start a club and began recruiting classmates in UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science.

“It was very easy to get people interested in joining us. Space is cool right now,” he said.

Today, the club has 35 members. While most students are studying engineering or computer science, CubeCats is open to all UC students and is looking to grow.

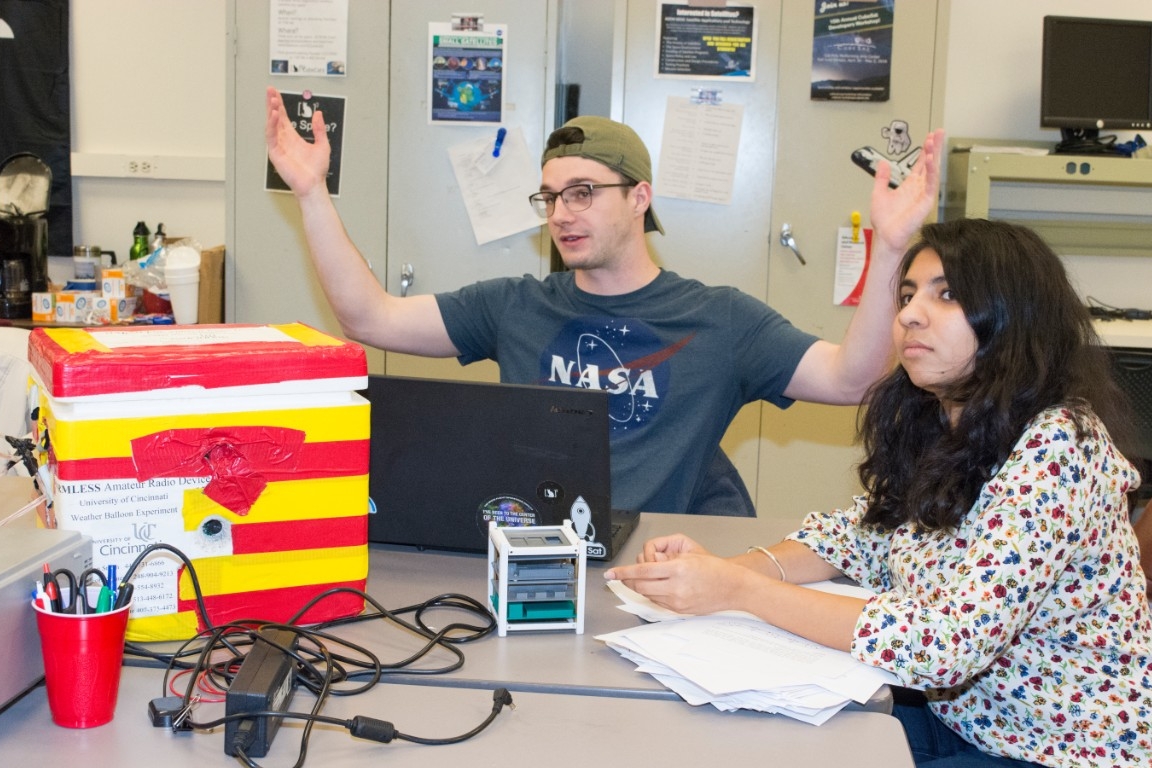

UC CubeCats founder Adam Herrmann, left, and President Himadri Pandey talk about the many space projects they considered before choosing to study radiation in space.

CubeCats President Himadri Pandey first dreamed about space as a third-grader when her grandparents shared the exploits of India’s first female astronaut aboard the space shuttle.

“For the next year, when anyone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said I wanted to be an astronaut like Kalpana Chawla,” she said.

Pandey followed her interest in computer science to UC, where she enrolled to take advantage of the university’s esteemed cooperative education program. But her early space dreams weren’t finished with her.

“I always thought space was cool. When I had a chance to join the club, I thought sure!” she said. “My interest grew the more I learned about it. I started going to conferences. There is so much to learn, but the community is so amazing.”

Himadri said she was delighted by NASA's announcement.

“It seems surreal. We have been looking forward to this day for more than two years now,” she said.

The UC club won grants totalling nearly $200,000 to design and build its first two cubesats. All nominated projects must address real problems related to NASA’s strategic goals.

The space shuttle Columbia lifts off from Kennedy Space Center in this 1993 NASA file photo. The crew of Columbia, including Indian astronaut Kalpana Chawla, were killed when the space shuttle broke up on re-entry during a 2003 mission. It was Columbia's 28th mission. (NASA)

“For the next year, when anyone asked me what I wanted to be when I grew up, I said I wanted to be an astronaut like Kalpana Chawla.”

‒ UC student Himadri Pandey, president of the UC CubeCats

Kalpana Chawla. (NASA)

The club brainstormed 33 ideas for its first cubesat mission before picking one, LEOPARD Sat-1 (CubeCats projects have cat names, naturally).

LEOPARD, an acronym for Low-Earth Orbit Platform for Aerospace Research and Development, will use sensors to test whether carbon composite can shield deadly radiation in space. It’s a serious concern for NASA, which has devoted an entire working group at the Johnson Space Center to studying space radiation.

A major challenge of proposed interplanetary missions is protecting astronauts from long-term exposure to harmful radiation in deep space, Pandey said. Particle radiation can pass through matter such as human skin and damage cells or even DNA, potentially making astronauts sick or more likely to develop cancer.

“This radiation is very harmful to our bodies. How we tackle that will be very important for a long journey to Mars,” Pandey said. “With our cubesat, we are testing radiation mitigation.”

The UC Cubecats captured photos from 96,000 feet during a successful high-altitude balloon mission in 2017.

“It’s like trying to take a photo from a bullet.”

‒ UC CubeCats faculty advisor Richard Beck on using cubesats to take pictures from space.

Sophomore aerospace engineering student Nathan Chiles is overseeing the club's first cubesat as the project’s chief engineer.

“I’m excited, nervous,” he said in the days leading up to NASA's announcement. “We poured hundreds of hours into the proposal last fall. It was a real crucible for us.”

Chiles said he hopes to develop the CubeCats into a national leader for cubesat research. He is encouraging students from colleges across campus to join.

“We recognize we can’t do everything. People bring different skill sets: advertising, promotions, legal,” he said.

The club’s organization and training program ensures that younger students will be prepared to take over when current officers graduate, he said.

“We want to make sure all the knowledge and experience gets transferred to the club. So (graduating) officers tutor the newly elected members for several months in their new positions to pass along that knowledge,” he said.

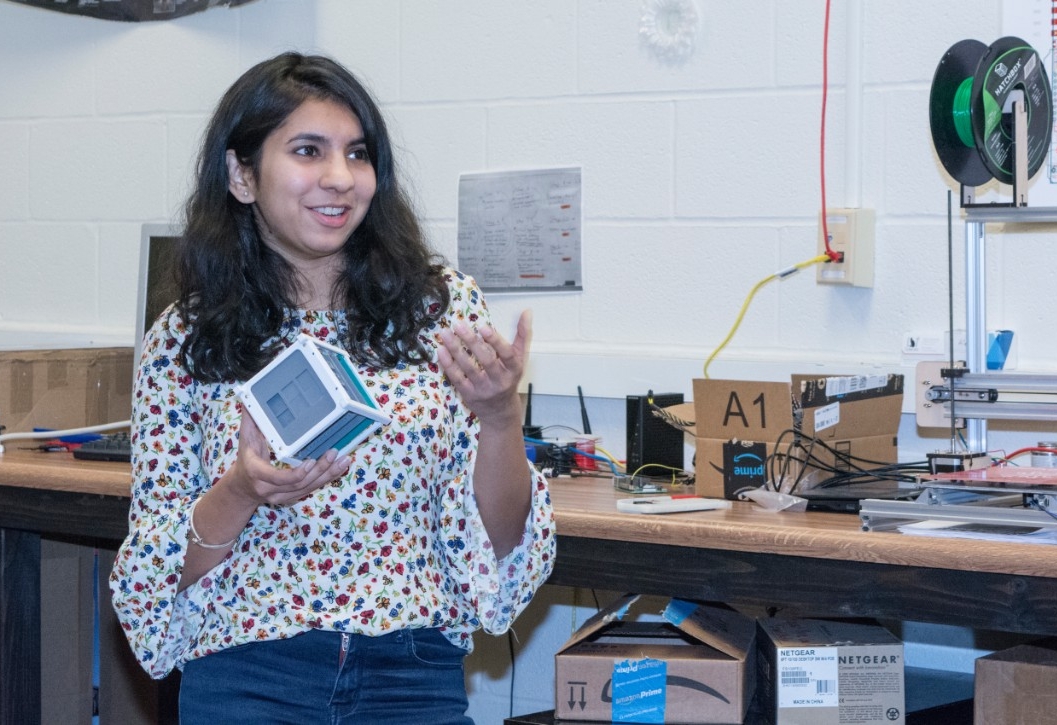

UC CubeCats President Himadri Pandey holds a model of a cubesat in the club's lab.

LEOPARD is supported by $60,000 in grants from MOOG Space and Defense Group, UC’s University Funding Board and the Ohio Space Grant Consortium.

Once constructed, UC's cubesat will be sent to a lab in California for shock, vibration and pressure testing to ensure it can withstand the rigors of space flight and deployment. After successful testing, it will be launched and deployed into low Earth orbit along with other cubesat projects NASA selects.

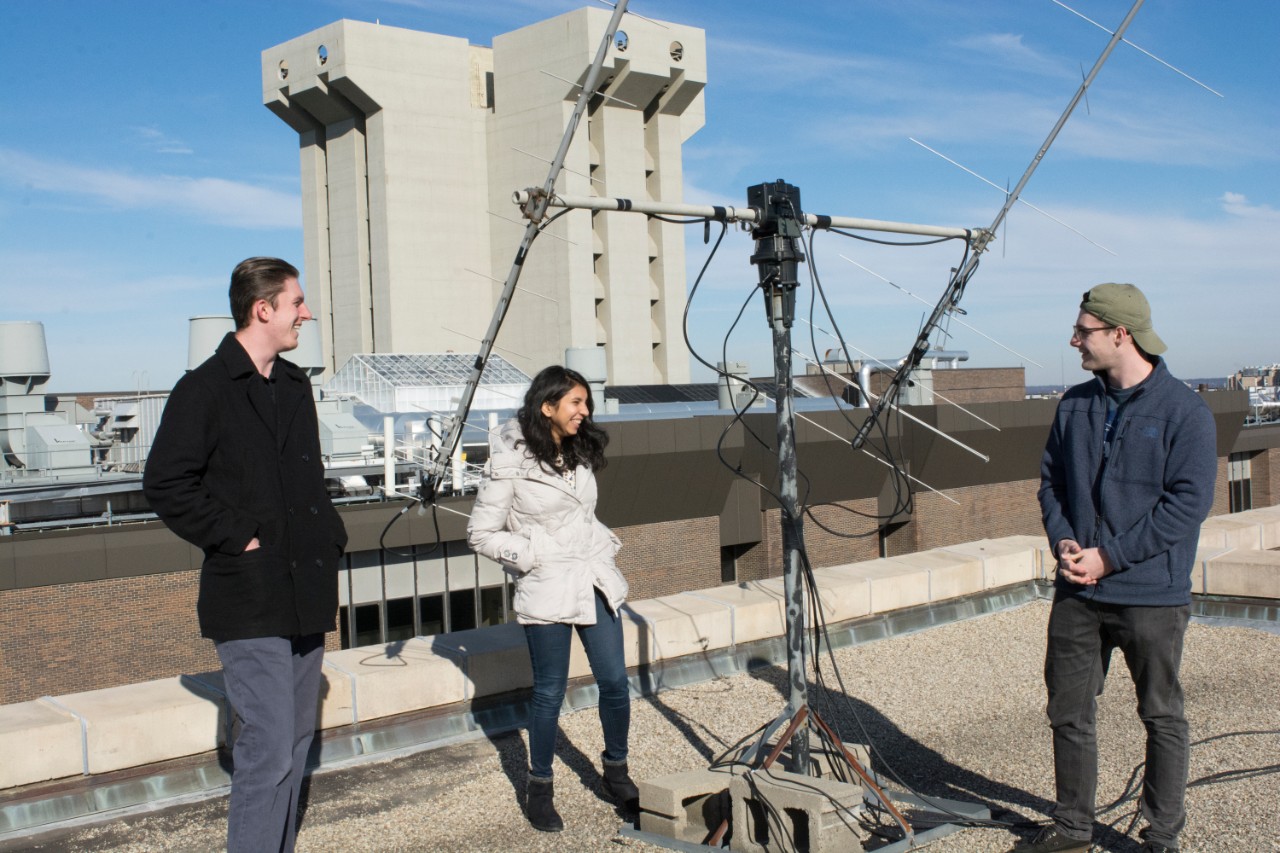

Once the cubesat is in orbit, the students will link to it by way of a UHF-VHF antenna the club is borrowing from the UC Amateur Radio Club atop the university’s Old Chemistry Building. Herrmann said they plan to add an S-band antenna, the same microwave band the International Space Station uses to transmit data. They also plan to install a motor drive so the antenna can track the satellite’s path across the sky.

UC CubeCats members Alex McGlasson, left, Himadri Pandey and Adam Herrmann talk about sharing the UC Amateur Radio Club's antenna atop the Old Chemistry Building to download data from orbiting cubesats.

UC CubeCats members Alex McGlasson, left, Adam Herrmann and Himadri Pandey pose atop the Old Chemistry Building.

UC’s second as-yet-unnamed satellite project, supported by a $130,000 grant from the Ohio Department of Higher Education, is designed to take detailed photos of Lake Erie from space.

UC will propose launching multiple cubesats into orbit to help the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) track toxic algae blooms in the Great Lakes. Algae releases toxins that can poison supplies of drinking water. In 2014, the city of Toledo, Ohio, warned residents not to drink water from their taps because of an algae bloom. Water treatment plants are not equipped to filter toxins generated by algae.

Algae forms soupy green layers that are so vast they can be seen from space. They are fed by an abundance of nutrients in the water, often from man-made sources like industrial and agricultural runoff that gets washed into the Great Lakes from creeks and rivers.

UC’s cubesats will take photos of Lake Erie to help scientists track algae blooms. But first the students will have to engineer the tiny satellites to orient themselves properly to capture images while traveling at 17,000 mph.

“It’s like trying to take a photo from a bullet,” said Richard Beck, associate professor of geography at UC and a faculty advisor on the project.

UC aerospace engineering student Jessica Kropveld is overseeing this project as its chief engineer.

“The big problem is cloud cover is too frequent to monitor the Great Lakes with just one cubesat,” Beck said. “We might get one clear pass out of every four. So we’re thinking it might take as many as eight to 16 cubesats to improve our chances.”

UC’s project was endorsed with letters of support from NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, both of which are studying the toxic algae, Beck said.

“The problem is only getting worse as the climate gets warmer and we have more nutrient runoff into waterways,” he said.

Beck said he is impressed with the drive and resiliency the student club has shown so far, particularly in their peer-leadership program that trains the next crop of officers.

“The CubeCats are very resourceful. They’ve done an amazing job. Large organizations in the government would be lucky to have the same effectiveness,” he said.

Cincinnati native and Walnut Hills High School graduate Grace Gamstetter is studying computer science but joined the club nearly three years ago to learn more about aerospace engineering. She is preparing flight software for the club's first cubesat.

“Space has always interested me, but I never thought I’d be able to do anything with it,” she said.

“I’m the first engineer in my family. In CubeCats, I’m learning teamwork. Team-based projects are huge,” she said. “I also learned about grant-writing, writing proposals and designing projects.”

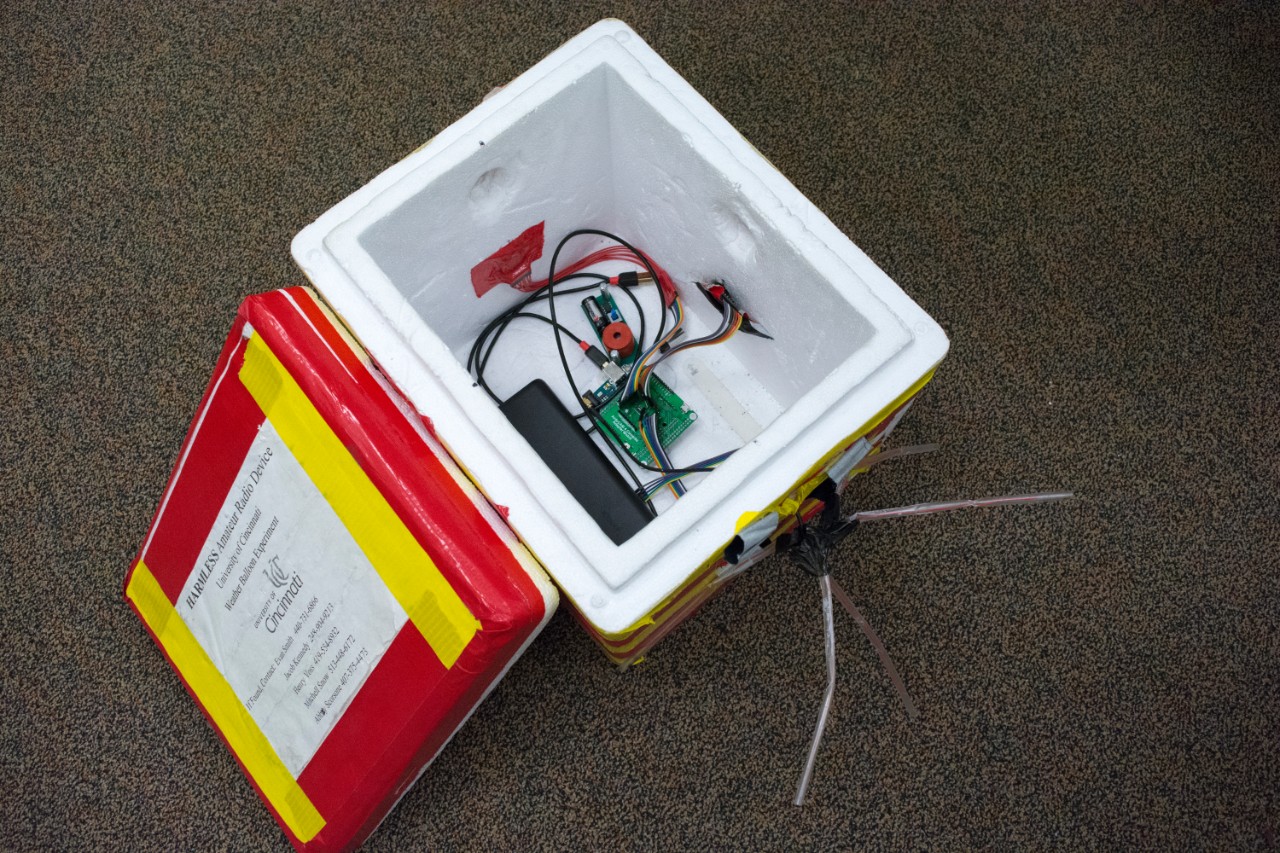

The UC CubeCats launched a repurposed drink cooler more than 90,000 feet above the Earth during a successful 2017 balloon mission.

The UC CubeCats presented their projects last year at the Small Sat Conference in Logan, Utah. (Provided by CubeCats)

Cubesats can be prohibitively expensive and require a partner agency for every launch. So UC’s club decided to mimic a satellite launch by building a payload for a high-altitude weather balloon. This scaled-down version of a cubesat gives novice club members an introduction to planning, designing and executing a complicated cubesat project as a team combined with the practical experience of a real launch.

UC engineering student Alex McGlasson supervises the club’s balloon projects.

“It’s the same design process you’d use for a cubesat, but at a lower cost, a lower risk and with significantly less time,” McGlasson said. “It takes one year and $1,000 to build one of these compared to three or four years to build a cubesat for $50,000.”

Club members repurpose a Styrofoam cooler to hold cameras, batteries, sensors and communications equipment. They launch the payload with a helium-filled weather balloon designed to pop at a certain altitude. The payload is designed to fall gently back to earth under a parachute.

The club launched Project Maine Coon (another cat name) in 2016 and tracked the balloon until losing radio communications somewhere over Virginia. They lost the payload in the mountains.

Last year the club regrouped and launched a second weather balloon, Project Toyger (another cat), which was outfitted with sensors to record atmospheric radiation and photonic measurements. Club members covered the cooler in reflective red and yellow tape and added a noise beacon that would sound for up to 36 hours. In bold print, they marked the outside of their repurposed drink cooler “HARMLESS Amateur Radio Device,” lest a box of shrieking electronics falling from the sky stirs public alarm.

This time the club recovered the payload from a farmer who found it in a field. The balloon’s four panoramic cameras captured stunning images of the curvature of the Earth at 96,000 feet.

“Our freshmen really love working on it. It’s hard work but they love it and have a lot of fun,” McGlasson said.

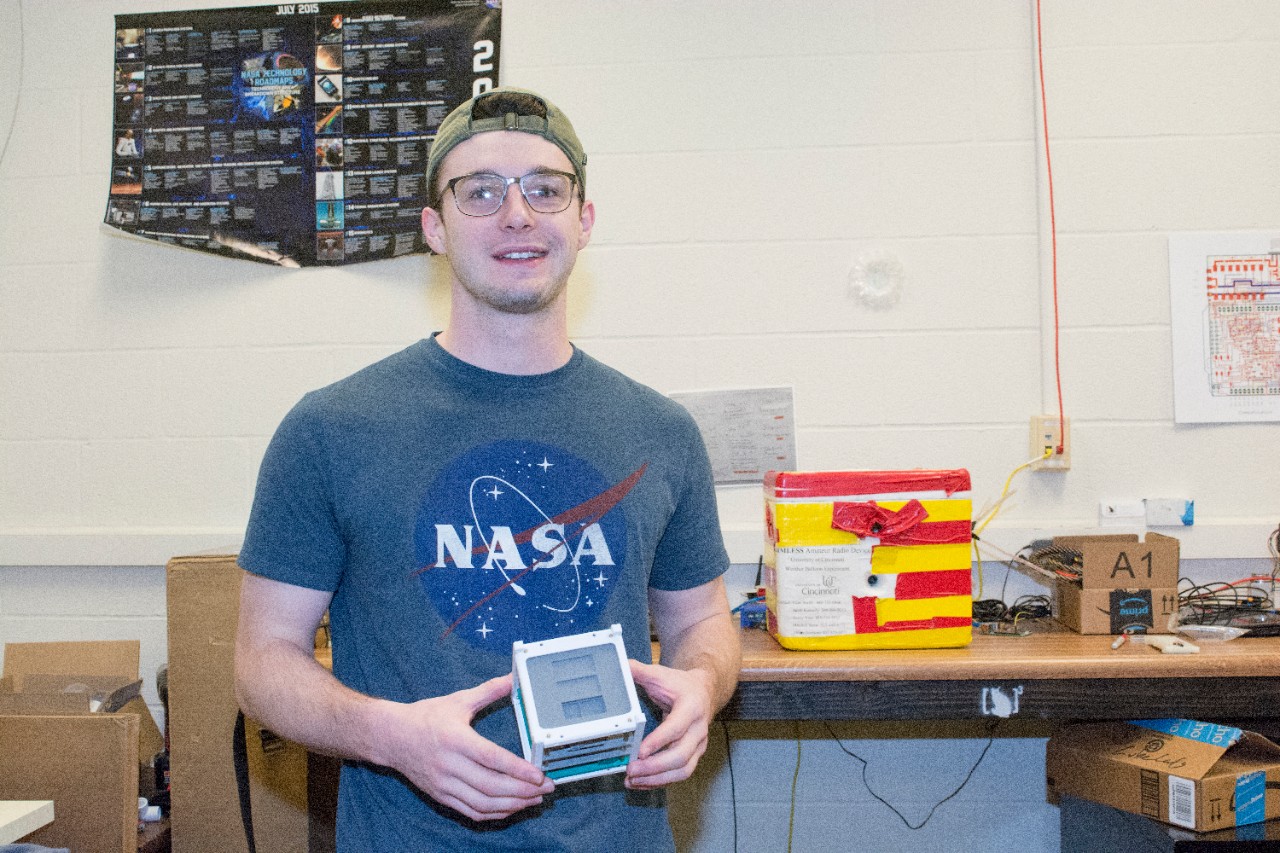

UC CubeCats founder Adam Herrmann holds a model of a cubesat in the club's lab. On the bench behind him sits the payload from the club's successful 2017 balloon launch.

Club advisor Catharine McGhan, an assistant professor of aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics, said the balloon launch is a cost-effective, scaled-down version of a real NASA space mission.

“You have to deal with a lot of the same constraints: the weight distribution and mass of the payload, the cold of the environment, even radiation. Virtually everything that you might put on a cubesat,” she said. “It takes a lot of good engineering to have all of that work.”

The club’s projects provide quintessential experience-based learning. UC recognizes the club as a student-based research lab, McGhan said.

“You have to practice it to understand it. The students I’m working with are applying the techniques they’ve learned in the classroom by going through a full design, build, test and launch,” she said.

Pandey has co-ops lined up at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and CERN, home to the Large Hadron Collider. She took her burgeoning interest in space to Silicon Valley last year for her first UC co-op at Pumpkin, which specializes in making nanosatellites for low Earth orbit.

“Apart from working with the software, I was able to learn about the different subsystems and how they work together,” she said. “I contributed to work that was presented at the Cal Poly CubeSat Developers’ Workshop in the spring. It was one of the most amazing experiences I ever had.”

Herrmann expects to graduate before the launch of LEOPARD. He is most proud that the club he founded has attracted the interest of new UC students who promise to keep the CubeCats going for years to come.

“This year’s high-altitude balloon teams have done a phenomenal job,” Herrmann said. “I’m super excited to see where things go with the club and to see how the younger members pick up the torch and carry it forward.”

Members of the UC CubeCats pose on the steps of Baldwin Hall. (Photo by Reeve Lambert)

Launching big ideas

Do you have research ambitions? At UC, students work on interdisciplinary projects with peers and professors from other colleges to turn their ideas into real-world projects. Check out the College of Engineering and Applied Science or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.