By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

April 28, 2017

Carlton Brett, a geology professor at the University of Cincinnati, recalls the first fossil he ever found while growing up outside Buffalo, New York.

“I remember flipping up a big slab of sandstone in the backyard,” he said.

On its underside was the imprint of an ancient clamshell. The surprising find made his 10-year-old imagination reel over the shallow ocean that once covered what is now North America.

“It wasn’t a great fossil, but I was so impressed. I knew it must be old. You could clearly see the ribs of the clam,” Brett said. “After seeing that fossil imprinted on the rock that day, I knew paleontology was what I was going to study.”

The thrill of discovery has intrigued Brett and generations of other paleontologists in a fossil-hunting club called the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers.

"The Dry Dredgers have had a profound impact on my graduate studies here at UC."

‒ UC graduate student Timothy Paton

The group, which has deep ties to UC, celebrates its diamond jubilee this month, marking 75 years of fossil collection, analysis and research that has helped shape how scientists view Cincinnati’s strange underwater world 450 million years ago.

The club has had a transformative influence on generations of UC geology students, according to their professors.

“Virtually every student doing paleontology work at UC has benefited from the Dry Dredgers,” said David Meyer, a paleobiologist and professor emeritus of geology in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

UC geology professor emeritus David Meyer holds a trilobite fossil in a UC geology lab full of specimens, some donated by the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers.

The club leads monthly field trips to creeks, quarries and other places that harbor recently exposed fossils. Many of these excursions are open to the public. And they have regular meetings where they share scientific discoveries and debate the findings. Some of the Dry Dredgers’ amateur members even submit research articles to geology journals and attend conferences.

But for UC the club’s influence is felt most among geology students, Meyer said. Members often give students newly discovered fossil specimens or help students find their own to study.

“The Dry Dredgers have had a profound impact on my graduate studies here at UC,” geology graduate student Timothy Paton said.

He goes to club meetings and accompanied members on fossil-hunting expeditions to New York and Ontario.

“They have shared their numerous discoveries,” he said. “They have even taken the time out of their schedules to guide us to field sites around Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.”

Paton was the beneficiary of the club’s annual paleontological research award, which he used to complete his master’s research. The Dry Dredgers donated thousands of dollars in grants for UC research. More importantly for Paton, Dry Dredgers foster a spirit of camaraderie, rooting for the success of students, he said.

“The greatest impact they've had on me is being so friendly and encouraging,” Paton said.

The late UC geology professor Kenneth Caster confers with other members of the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers over a find during a 1977 outing. (Cincinnati Dry Dredgers photo.)

The Cincinnati Dry Dredgers was founded by the late Kenneth Caster, a UC geology professor who helped develop the first theories of plate tectonics and continental drift.

“Ken was a great paleontologist and an internationally renowned scholar. He was a wonderful professor,” Meyer said.

Caster, a Cornell University graduate, was an avid fossil collector who found a bonanza awaiting him when he came to teach at UC. The club owes its existence, at least in part, to Cincinnati’s well-deserved reputation as a hotbed of Ordovician fossils such as ancient sea lilies called crinoids and trilobites, a species of which is the Ohio state fossil.

“People came here to study them. We have the rocks and fossils right under our feet,” Meyer said.

Greater Cincinnati was built atop a geological feature named the Cincinnati Arch in which the ground around the Tristate heaved up while surrounding areas subsided. This exposed a rare bounty of Ordovician fossils, drawing interest from experts around the world.

Caster and other paleontologists spent afternoons together collecting these fossils by the bucketful in road cuts formed by Works Progress Administration highway projects. He formally established the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers as a club in 1942.

To find fossils, you need a practiced eye and determination, Meyer said.

“It takes a lot of time to find good fossils,” Meyer said. “Members of the club are the primary finders of good fossils in this area. They’re mostly amateurs but they dedicate a lot of time in the field.”

"You can't go out for two hours a month and think you're going to find anything unusual. You have to be persistent."

‒ Jack Kallmeyer, president of the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers

Club president Jack Kallmeyer often can be found scouring likely fossil troves, digging his rock hammer into an exposed hillside to keep from slipping as he searches for telltale shapes or colors that betray a fossil among the scree.

“You can’t go out for two hours a month and think you’re going to find anything unusual. You have to be persistent,” he said.

Kallmeyer donated 12,000 fossils from his personal collection to UC and Ohio University. He spent his career as an engineer but his heart was always in paleontology, he said.

“If I had known more about UC's geology department, I would have switched my major,” he said.

While many club members are technically hobbyists, some are experts in their own right.

Members William White and Stephen Felton received the Paleontological Society’s highest honor granted to amateurs, the Harrell L. Strimple Award, for their contributions to science.

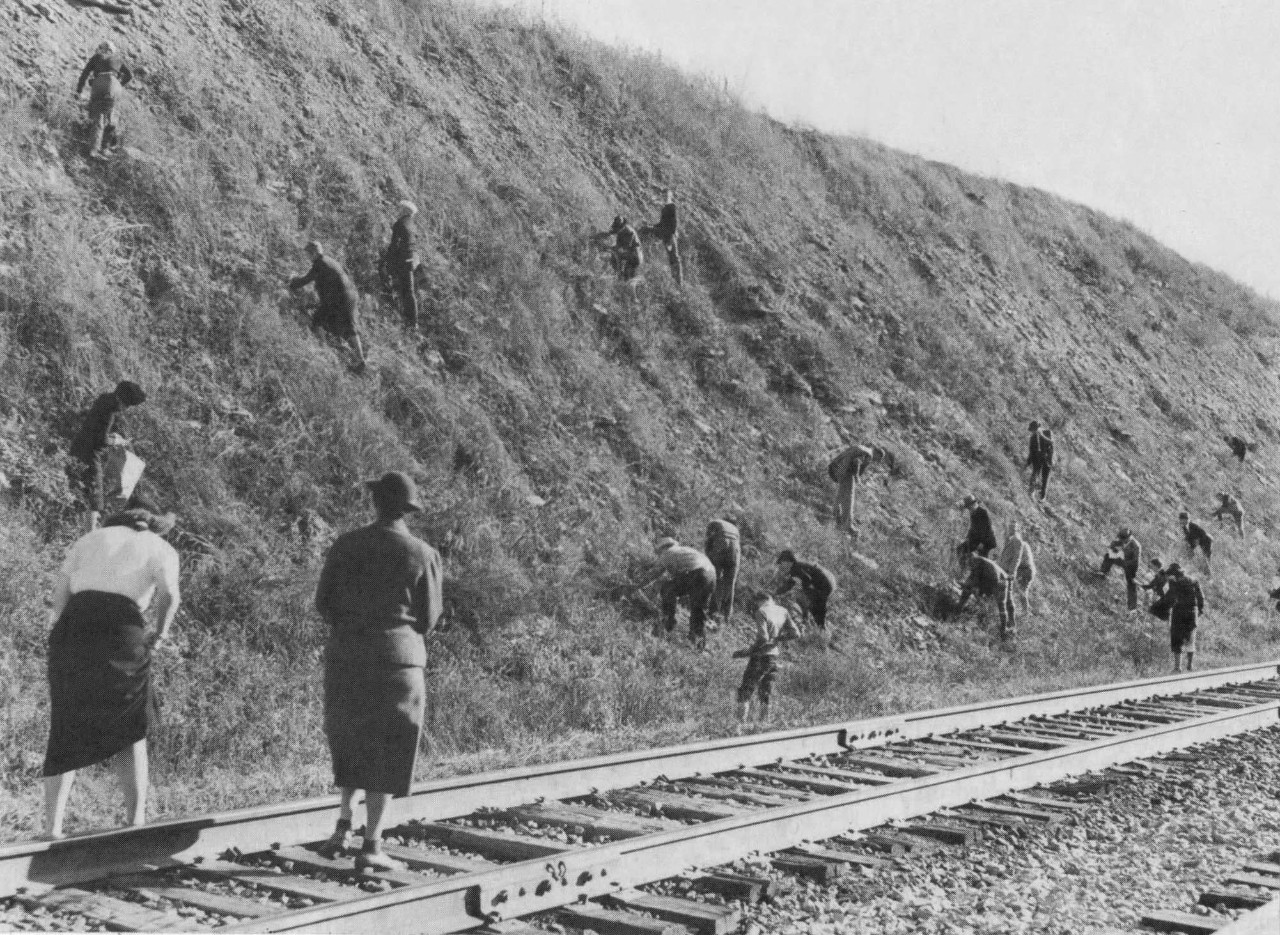

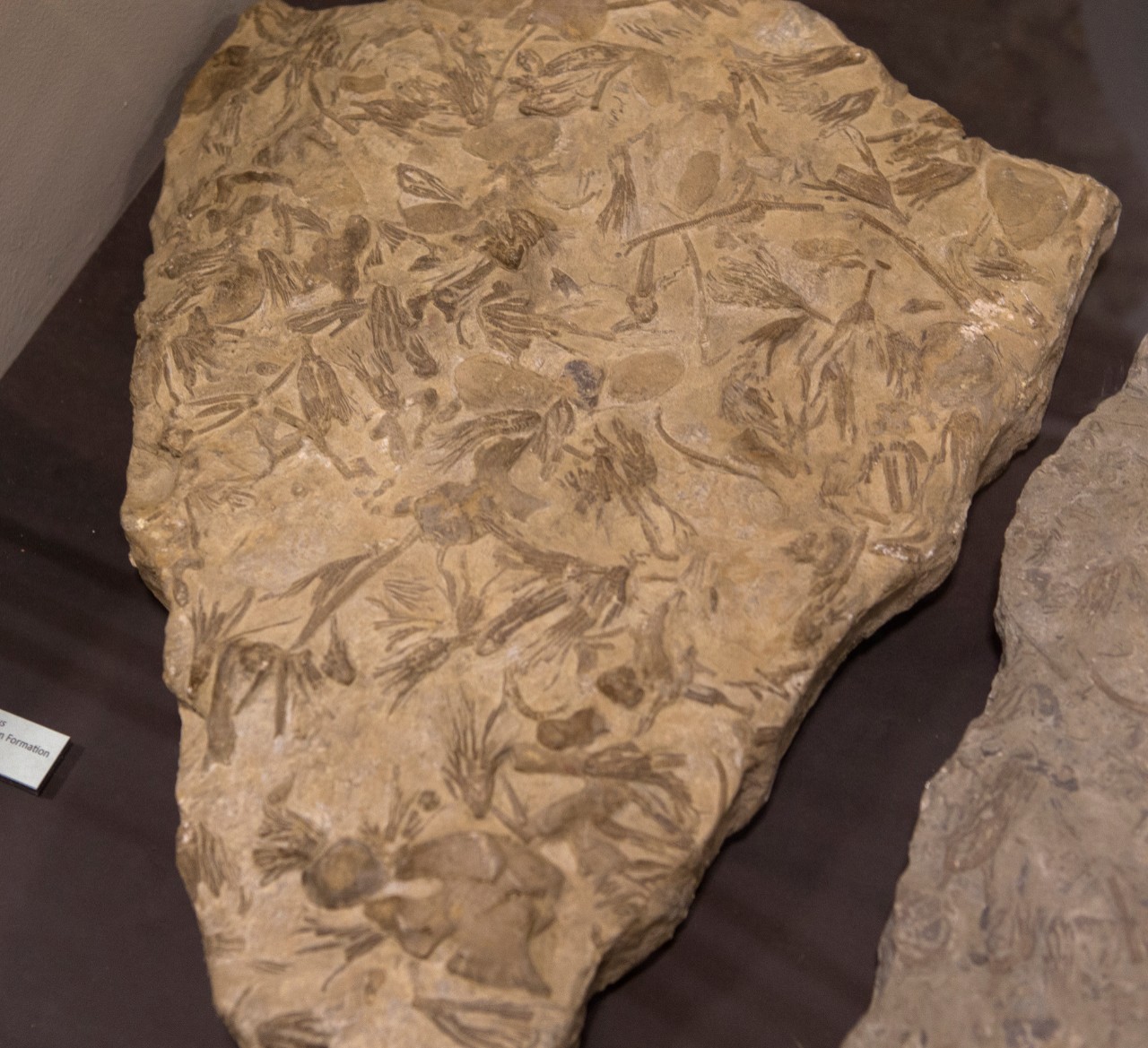

UC geology professors and students, above, collect specimens at a railroad site in Berea, Kentucky, in this 1938 photo. Organizers of these outings would create their own club, the Cincinnati Dry Dredgers, in 1942. Today, the club collects many of the fossils on display at UC, left, and Cincinnati's Museum of Natural History and Science. (Cincinnati Dry Dredgers photo.)

One day in his UC office, Meyer showed off some fossils from his own collection, including trilobites and teeth from a prehistoric shark called megalodon. Despite working at a landlocked university in Ohio, Meyer dove off reefs all over the world to study the living descendants of ancient animals. He has dived every year for the past 50 years, including a trip last year to Cuba.

Meyer wrote a book on fossils with Richard Arnold Davis of Mount St. Joseph University titled, “A Sea without Fish.” The book contains photos of Cincinnati-area fossils collected by the Dry Dredgers. Now he is cataloguing 50 years’ worth of underwater photography that documented marine life from his reef expeditions while at UC.

“For me at UC, it didn’t matter that I lived hundreds of miles away from the ocean. I could still pursue my interests,” he said.

Fossil collectors have no hope of uncovering a tyrannosaurus or triceratops in Cincinnati. The Ordovician Period predates dinosaurs by hundreds of millions of years. Many of these younger fossils were pulverized by Ohio’s glaciers and wiped away by erosion.

But the region does have evidence of the megafauna that once roamed its plains and forests. Northern Kentucky’s Big Bone Lick State Park is home to ice age fossils of mammoths, dire wolves and sabre-toothed tigers.

Professor Brett said the fossils have aesthetic appeal beyond their scientific value. When he picks up a trilobite fossil and sees how the ancient shale preserved its delicate, alien eyes, he is transported.

“You’re looking at eye lenses that captured their last image about a half-billion years ago,” he said.

Brett followed his passion to UC, where he teaches paleontology and conducts research on ancient environments and sea levels to learn more about the forces behind evolution and extinction. The prospect of discovery still fills him with the thrill of anticipation.

“You see these fossil remains as they were on they day they were buried. Every time you split the local Cincinnatian rocks you are opening sediment layers that haven’t seen the light of day for more than 440 million years. That’s profound."

Fossilized sea lilies called crinoids

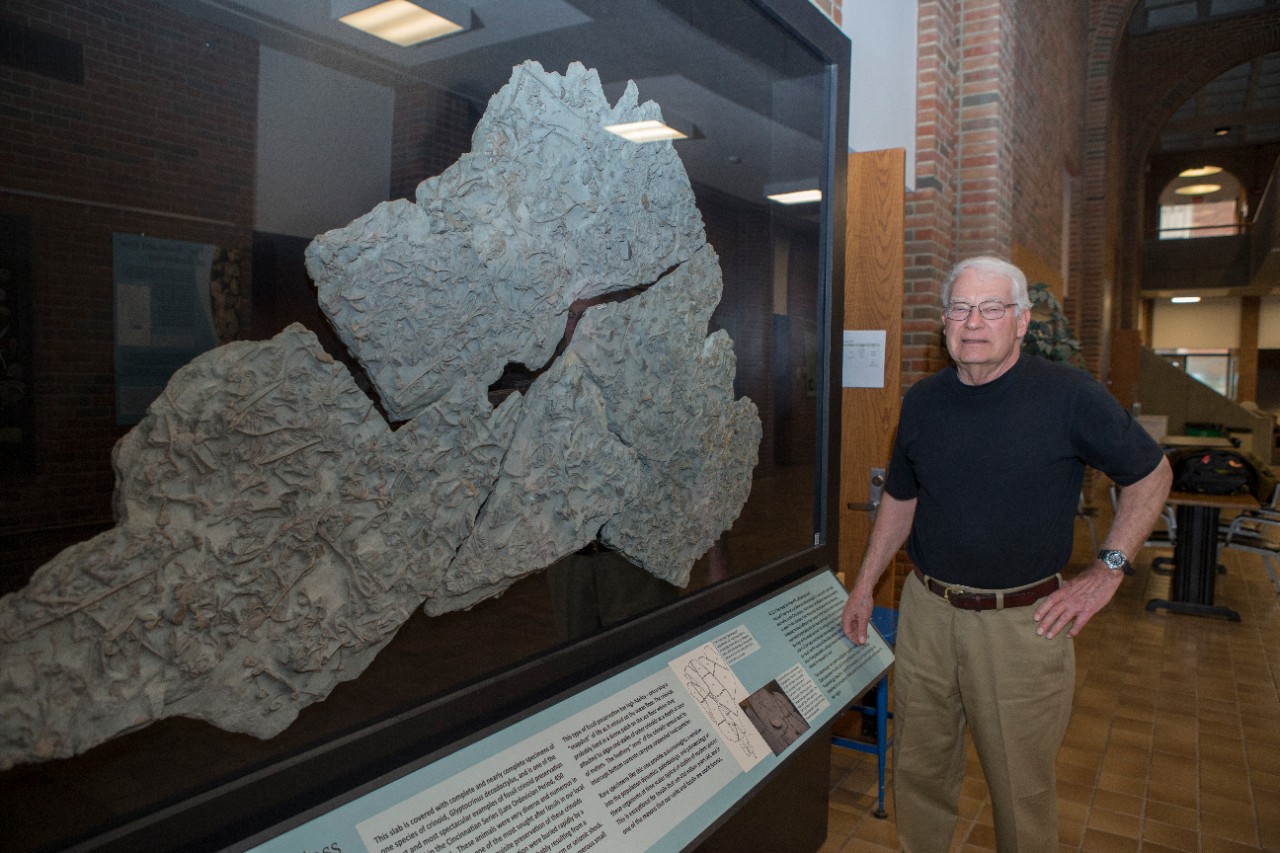

UC geology professor emeritus David Meyer stands in front of a slab of crinoid fossils on display at UC.

A trilobite fossil on display at UC.

Do you have an adventurous spirit? At UC, paleontology students have a chance to conduct hands-on research. Apply to the Department of Geology or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.