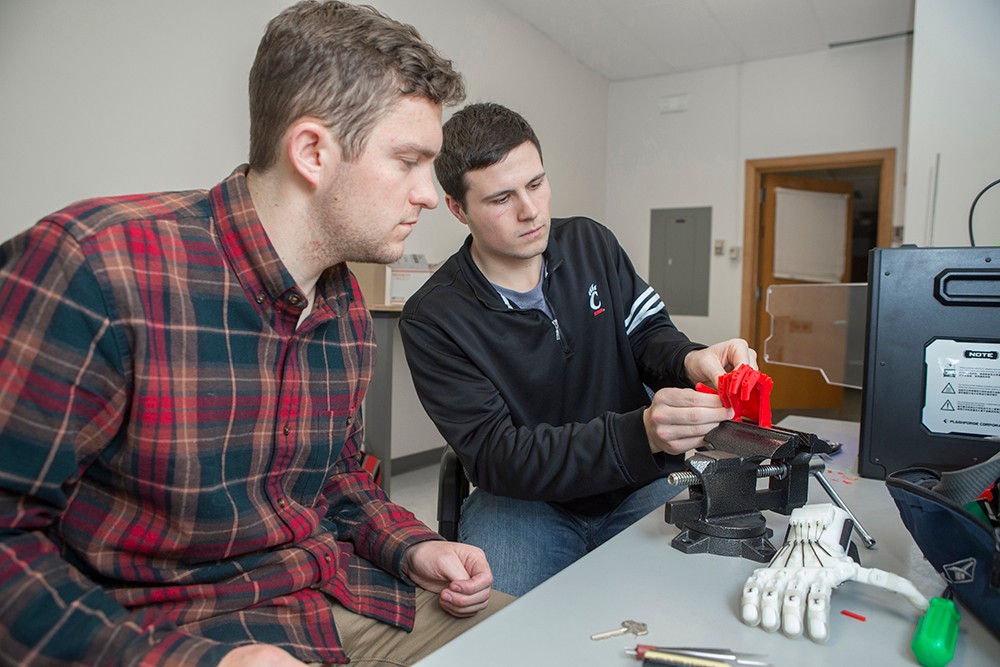

EnableUC president Jacob Knorr and co-vice president Nick Bailey work on a 3-D printed prosthetic hand. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

A hand up

Student organization enables patients with disabilities, future engineers with 3-D printing

by Jac Kern

513-556-1823

photos by Joseph Fuqua II,

UC Creative Services

Jan. 18, 2017

T.J. McGinnis had never been to the University of Cincinnati before last October. The 15-year-old toured the campus, stopping at Nippert Stadium — a place of interest for the high school varsity football player. But that wasn’t his only “first” that day. Born with just a partial right hand that barely extends beyond his wrist, he’d never experienced using two hands before. That was about to change.

T.J. McGinnis plays varsity football for Rock Hill High School. Photo/provided

Thanks to a student organization, EnableUC, McGinnis received a 3-D printed prosthetic hand, allowing him to grasp and release objects, shake hands and utilize five fingers he did not otherwise have with a device created by students, on campus, for less than $20.

Founded by Jacob Knorr, a 22-year-old biomedical engineering student in the College of Engineering and Applied Science who serves as the organization’s president, EnableUC provides affordable 3-D printed prosthetic devices to those in need locally, regionally and beyond. The group also works to find new ways to apply 3-D printing to various medical problems.

Before starting EnableUC, Knorr worked as a co-op student at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in the Division of Plastic Surgery, conducting research to address craniofacial abnormalities like cleft lip and palate bone defects. Still working there today, Knorr utilizes 3-D printing to create tissue-engineered “scaffolds” used to promote bone regeneration.

“I worked through my co-op jobs and school, and I found this interesting parallel between my research and my interests,” Knorr says.

As he became more fascinated by the possibilities of 3-D printing, he read an article about a civil engineer who created a cost-effective 3-D printed prosthesis for a veteran who had lost his fingers in an accident.

“I thought it would be really cool to bring something like that to UC,” he says.

With the help of other biomedical engineering students and faculty and with grant funding, EnableUC secured a 3-D printer and became a recognized organization in October 2015. Today the group is comprised of around 30 members, 12 of which are on the executive board, and organization advisor Dr. Chia-Ying Lin from the CEAS Department of Biomedical Engineering.

Knorr says 3-D printers provide ample opportunities for students in particular.

“You don’t need to be any kind of expert to make something with complex architecture, whereas you would [otherwise] need a machinist, very expensive tools and other materials.”

EnableUC created a device to help recipient T.J. McGinnis carry out everyday tasks. Photos/provided

Knorr and the other students in EnableUC can make a prosthetic hand that’s not only affordable, but also patient-specific. After identifying a patient who has some wrist movement and either a palm without functioning fingers or a partial palm, the team downloads a design file of a mechanical hand device from e-Nable — a global network of volunteers and open source organization that provides cost-effective prosthetic hand designs — and scales it to the size of the hand. The patient doesn’t even need to be present; all EnableUC needs is a photo.

That file is put through a “slicer” program that allows the 3-D printer to read it and then print each part of the device, extruding plastic layer by layer. Nearly every individual part of the devices are 3-D printed, even the pins.

The team then assembles the hand, adding strings to help with movement, and within just hours the device can be completed for a cost of around $20 — no batteries or robotic components necessary. The prosthesis works mechanically off of wrist movement, which controls the fingers. For a patient without wrist movement, there are larger devices that work off of elbow movement. Alternative prostheses require a physical therapist and a lengthy fitting process, and can range anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000, depending on the complexity.

A completed device (above) lays next to a work in progress. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

“The idea is not to make something that’s state of the art,” Knorr says, “it’s to make something accessible that can help people. The reality is many people are not going to be able to afford that or they’re not in the position to use those.”

Children are a key demographic.

“Pediatric prosthetics is an area of need where 3-D printing can address that cost. Children are going to grow out of hands quicker than you could ever pay to supply them with a conventional prosthetic hand or arm.”

Kids with a device from EnableUC don’t have to worry about a growth spurt or playing too rough — if the hand breaks or no longer fits, another can be printed and built again. And getting children accustomed to using an assistive device early can be very beneficial long term.

“If you ask any physician or hand therapist, they’ll tell you that if a child has never used a prosthetic before, as an adult they’re very unlikely to use one because they’re just not used to it,” Knorr says. “If you can give them a prosthetic early and keep up with their care throughout their growth and development, they’ll be much more suited to using something that’s maybe state of the art when they become an adult. We're not only thinking about care right now, but care in the future for disabilities.”

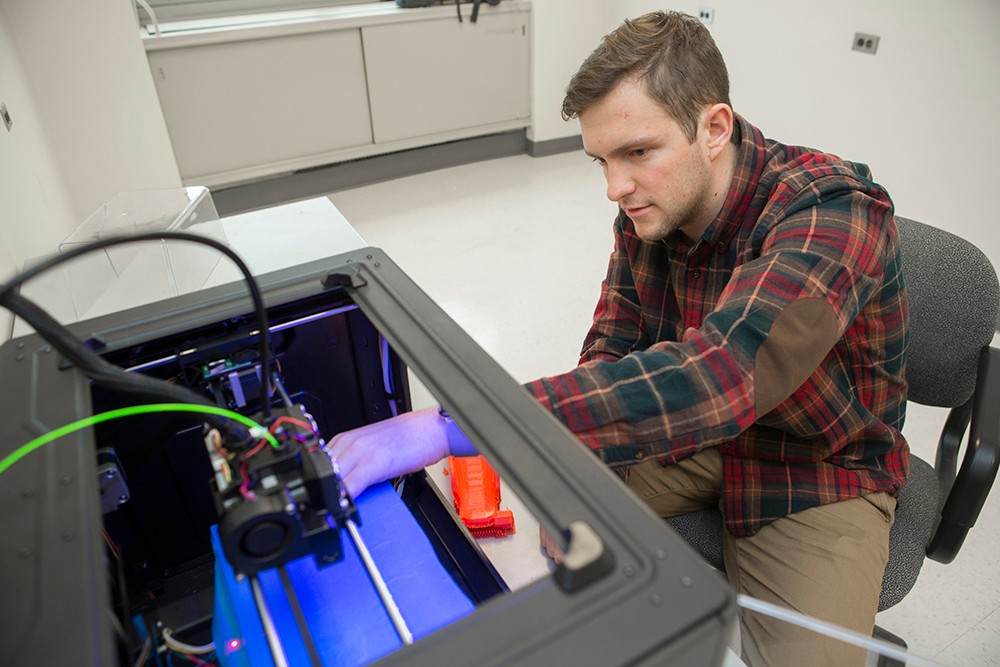

Jacob Knorr uses EnableUC's 3-D printer. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

EnableUC created its first hand for 13-year-old Cincinnati resident Brody Langdon in December 2015 and, more recently, built a small device for a 4-year-old who’d lost his hand in a farming accident. He received it as a Christmas present. The group has since provided an additional 40 patients with hands, arms and other assistive devices.

“We’re also working on assistive devices for physical therapy and occupational therapy,” Knorr explains. “Think of someone who has had a traumatic brain injury that can’t use their hand very well because they have nerve damage. We’ve designed devices for them to drink independently at the dinner table, hold a cell phone or a variety of other applications.”

For these devices, EnableUC has partnered with Touro University, an occupational therapy school in New York. The school sends prototypes and patient specs; EnableUC models the devices and sends them out. Again, the student organization can create devices for patients in any location, without ever having seen them in person. They’re also working with Cincinnati Children’s Hospital’s brachial plexus clinic to develop a prosthesis that will address nerve injury in the arm.

Photo/Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

Amid these projects, EnableUC looks to diversify and create new devices.

“It’s really great to take open-source designs from online and print them out and then give them to patients, but also we’re a university,” Knorr says. “We have a lot of engineers, people that like designing and building things. So we want to develop some of our own solutions.”

One idea is a myoelectric arm. Unlike the 3-D printed hands, this would be a battery-powered device that can sense muscle contractions — but still a cost-effective alternative to some of the more expensive prostheses on the market. It uses electrodes to detect muscle contraction in the arm, sending signals to motors to open and close the hand. The group is currently raising funds online for this project.

“This is really a robotic hand,” Knorr says. “You could think of it as a Luke Skywalker hand.”

Looking ahead, Knorr sees the potential for global applications, especially when it comes to 3-D printing. The low cost and quick turnaround time could offer health care options for people in need in war-torn or developing countries.

“We really want to expand to that next level to not only have an impact in the Cincinnati area, but an impact on a global scale.”

Members of EnableUC gather with prosthetic recipient T.J. McGinnis. EnableUC executive board members include Jacob Knorr, Nick Bailey, Yosef Kirschner, Brandon Christman, Eden Barcus, Gabrielle Notorgiacomo, Erik Angus, Ian Rawdon, Darryn Scott, Ishan Anand, Mike Fitzgerald and Allison Shaw. Photo/provided

EnableUC offers opportunities not only for patients, but for UC students and future engineers. Knorr describes the valuable experience his organization offers students, from learning computer modeling and the 3-D printing process to getting meaningful clinical exposure. The organization has recently started a mentoring initiative to get motivated underclassmen involved so they can understand the process. When the time comes for some of the board members to graduate, there will be knowledgeable members to fill their place.

“We’re not just about the people with disabilities; we’re about enabling the students here at UC as well,” he says.

That includes future UC students. The 3-D printing aspect is a great incentive to engage high school students who might be interested in engineering and medicine.

“We’re working on high school outreach to get that next generation of students interested so they can go to school for engineering,” Knorr says. “A lot of high school students don’t even understand what engineering is, so it’s definitely an area that can be promoted.”

That goal leads back to T.J. McGinnis, the high school football player who recently received a hand. McGinnis hopes to become a biomedical engineer, Knorr says, and is really interested in 3-D printing.

“When we finally presented him with a hand,” Knorr says, “we also gave him parts and everything necessary to build his own. So we’re promoting science and engineering while also helping him with his disability.”

“That’s definitely one of my favorite experiences so far.”

LINKS:

Learn more about EnableUC at enableuc.org and UC Campus Link.

GoFundMe

Twitter

Facebook