Photo/"End of an era" (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Unhindered by Talent

Evolution of Film Scoring

University of Cincinnati researcher chronicles the art form’s shift from theatrical orchestras to movie mixtapes

by Jac Kern

513-556-1823

March 29, 2017

Music can make or break a movie. Scores and soundtracks are an important formal component of film, something James Knippling has explored for the College English Association (CEA) National Conference in Hilton Head Island, S.C. The University of Cincinnati associate professor educator will present “Popular Music and the Hollywood Soundtrack of the New Hollywood Period (1967-1975)” on March 30.

Music has been a key part of film since the time of silent pictures and before that, in theatrical shows on stage. But in Knippling’s study of films from the mid-20th century, he noticed a stark change in how the music was employed, and his talk offers a historical comparison of music in what he calls the “classic Hollywood period” and that in the “new Hollywood period."

In the classic Hollywood period, the 1930s to '50s, nearly all films were accompanied by orchestral music. “The movie studios would keep full orchestras in constant employment, because they had to score every film they made, and they churned them out much quicker than today,” Knippling says. “That was a time before TV, when people would go to movies an average of three times a week.” He notes that a full orchestral score was used, regardless of the film setting. “Even if the film might be set out in the country with bullfrogs, you’d still have the orchestral score — you wouldn’t have harmonicas and banjos. It was universal.” The music should be a subliminal emotional cue — something the audience isn’t necessarily aware of.

“The idea of ‘unheard’ music goes hand in hand with the way in which the visual style of the classic period is usually described — the invisible style,” Knippling explains. “The camera’s not drawing attention to itself. It’s gliding around seamlessly, showing you what it hopes you will take as the unmediated ‘real.’”

Photo/"Milo Theater 1948" (CC BY 2.0) by Joe+Jeanette Archie

Film scores of the classic Hollywood period often used musical techniques that aided in the storytelling. A “stinger” (or a musical exclamation point, as Knippling describes it) is a sudden loud chord that signifies drama (think of that recognizable “Dun, dun, dun!” you might hear after a shocking revelation in a drama). A musical theme associated with a particular character, or a leitmotif, gives the audience more insight into that person, like when ominous music plays whenever a villain is on screen. Sometimes music can imitate the action happening in a scene. This is called “mickey mousing” because it’s similar to the way music is used in cartoons.

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho” (1960) features a lot of mickey mousing. Tense music syncs up with Marion’s windshield wipers as she drives in the rain and approaches the Bates Motel; later, in the fateful shower scene, that iconic screeching music mimics the stabbing — something Hitchcock almost didn’t use.

“Actually, Hitchcock didn’t want any music on the shower scene in ‘Psycho’ and [composer] Bernard Herrmann had to talk him into the stabbing sound,” Knippling says.

But musical techniques like mickey mousing and stingers often feel over-the-top today. “These old classics come to seem didactic and predictable at a certain point,” Knippling says. Filmmakers “move on to other modes of film scoring.”

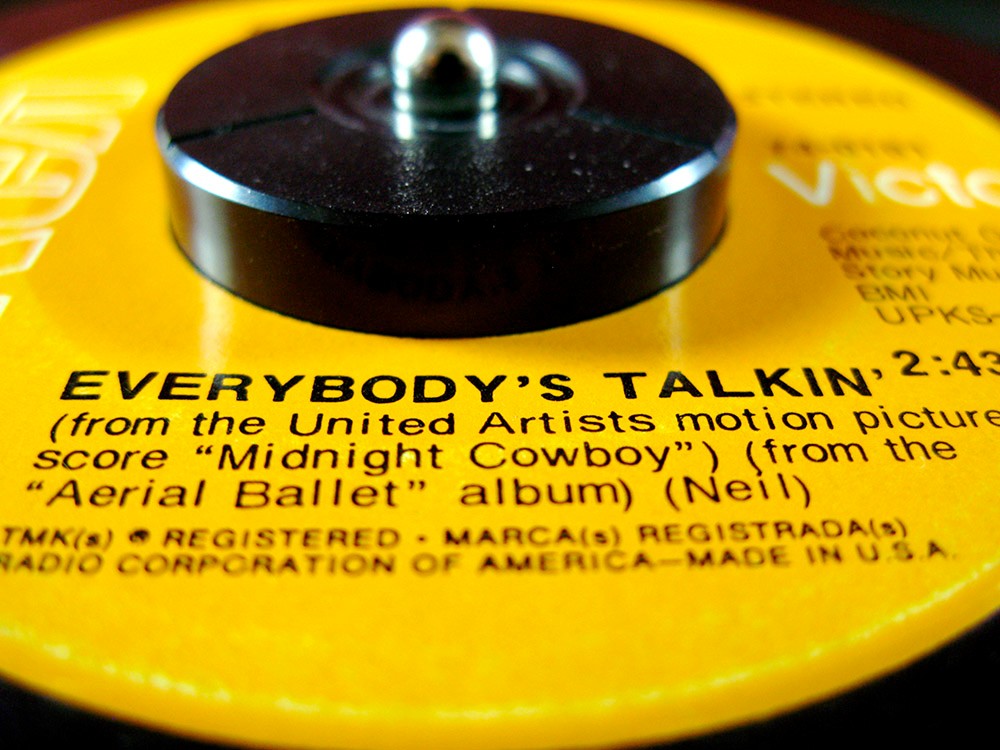

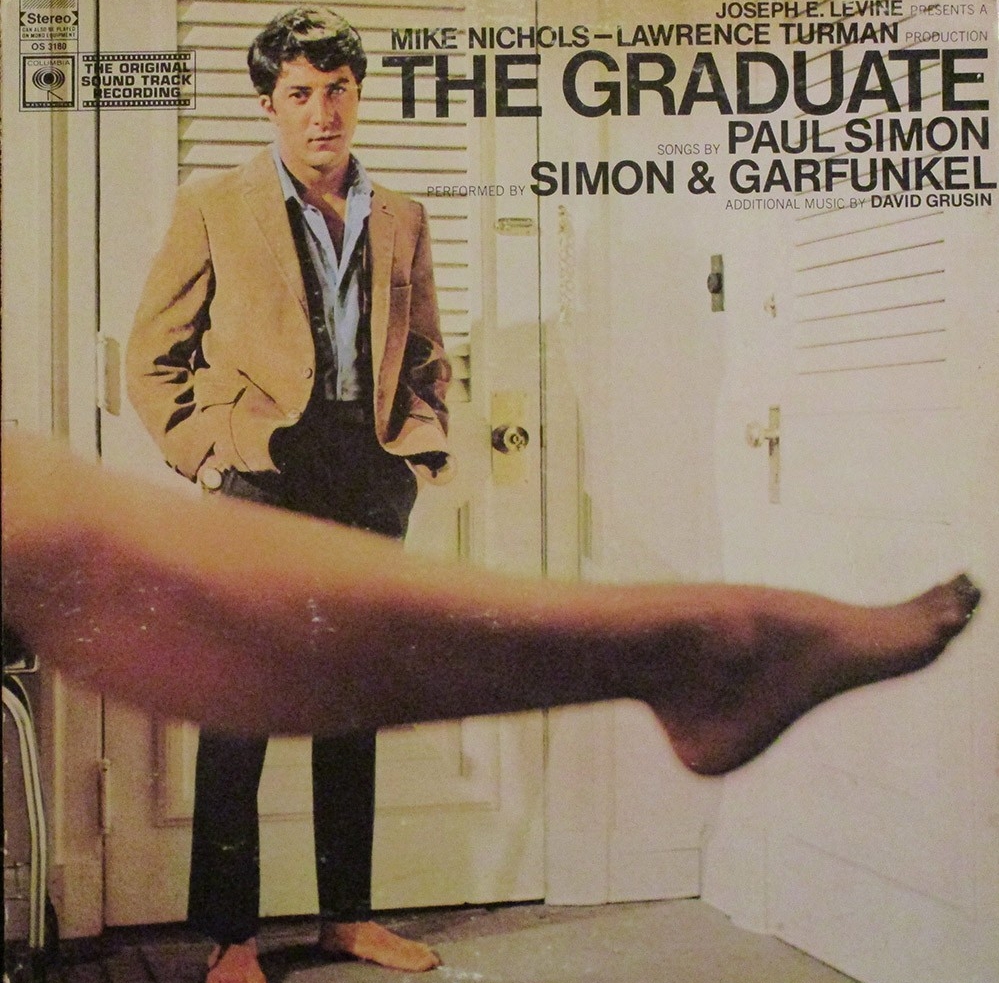

Beginning in the late 1960s, many movie studios did away with the full orchestras, with directors opting for pop music over original orchestral scores. Knippling notes two films that best represent this change: Mike Nichols’ “The Graduate” (1967) and John Schlesinger’s “Midnight Cowboy” (1969). “The Graduate” film score included several folk-rock songs by Simon and Garfunkel, while “Midnight Cowboy” used Henry Nilsson’s “Everybody’s Talkin’” prominently. In both cases, the songs (besides “Mrs. Robinson” in “The Graduate”) were already in release before the movies came out, which was unusual for the time.

“That’s an interesting transitional moment that hasn’t received a lot of scholarly attention,” Knippling says. “It’s what takes us from that orchestral period, during which the music would always be composed specifically for the film, to this modern moment, when every movie creates its own mixtape.”

Photo/"Everybody’s Talkin (Harry Nilsson)" (CC BY 2.0) by kevin dooley

Another film that ushered in this new wave of cinema was Arthur Penn’s “Bonnie and Clyde” (1967). The story of this infamous bank-robbing duo was set to banjo music, including "Foggy Mountain Breakdown" by Flatt and Scruggs — happy, playful tunes played during car chase scenes instead of darker, more serious music.

“The old code was always that you mark illegal activity by sinister music,” Knippling says. “So they’re actually having fun with this getaway? That was scandalous.”

While known today as one of the greats, “Bonnie and Clyde” was initially panned by many critics. Even the movie studio, Warner Bros., failed to get behind the film, doing minimal promotion and relegating it to drive-ins. It featured very graphic violence and sex scenes for the time, but Knippling feels the unique choice of music played a role.

“I think it upset people,” he says of the score. “[Journalists] didn’t write in their reviews, ‘I was offended by the banjo music,’ but you could kind of tell that this was part of the problem for them.”

This didn’t keep fans, particularly young people, from turning out at theaters to watch “Bonnie and Clyde.” Film critic Joe Morgenstern initially gave the film a poor review in Newsweek, but once he saw it again and noticed the enthusiastic audience, he retracted the review and gave a more favorable one. Time magazine also replaced its negative review with a more positive take. Longtime New York Times critic Bosley Crowther essentially lost his gig as the paper’s main critic for refusing to reassess his panning of the film. “Bonnie and Clyde” went on to garner 10 Oscar nominations.

“A movie that was kind of despised and then gradually takes on esteem is quite interesting,” Knippling says.

Of course, these trends represent more than just film score changes. They’re a sign of the times and the splitting of musical taste along generational lines.

“During the ’40s, if somebody put out a pop song, their target audience was really everyone from grandchildren to grandparents and everyone in-between,” Knippling says. “Musical taste begins to split in the ’50s with Elvis and even more intensively in the ’60s, when suddenly for young people music is a crucial part of their identity and not just entertainment. They just reject the old orchestral style.”

Around this time, audiences began to have a new investment in the authenticity of music.

“In the late ’50s, for example, if you look at the Billboard top hits, most of the songs are written by someone other than the person singing,” Knippling says. “What happens over the next decade is a coalescence of the singer-songwriter figure: Joni Mitchell, John Lennon, Bob Dylan, Paul Simon. What you’re hearing is the personal expression of the performer. So it’s almost inevitable that the authentic pop song is going to come into the soundtrack.”

As music and film trends constantly change over time, pop music in film continues to reign supreme today. “It seems like the best directors are people who have exquisite taste in finding that perfect pop song for that perfect moment,” Knippling says. He lists Wes Anderson, Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson as some directors known for their “movie mixtapes.”

After teaching more traditional English courses in the College of Arts and Sciences for years, Knippling now leads classes such as “Generation X Directors” and “Digital Composing.” This combination of English, film and multimedia studies will all be integrated into his CEA presentation on March 30.

Next up for Knippling is the International Association for Media and History conference in Paris, France this July. He will be giving a multimedia talk on the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan by John Hinckley.

LINKS:

College English Association National Conference

UC's Department of English and Comparative Literature in the College of Arts and Sciences

Apply to UC