Behind the mask this Halloween

By Melanie Schefft

513-556-5213

Photos by Adobestock

October 27, 2016

University of Cincinnati pop culture experts predict plenty of creepy clown masks this Halloween along with a deluge of costumes depicting both Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton.

But what is behind the thrill of the mask –– the mysterious identity switch –– if even for just a night?

According to University of Cincinnati researchers, it’s a way to escape.

Halloween, and the desire to wear the illusive mask is a way to escape from the norm, according to Eric Jenkins, UC associate professor of communications. People want to turn things upside down or, to do things differently than what they do in their everyday lives.

“It's a time of freedom from social norms, a way to purge or satiate some of our dark desires,” said Jenkins. “Masks allow us to do this temporarily without actually doing it ourselves — we do it as someone else.”

Clowning around

While clowns have always held a certain phobia for some, this year’s costumes present an extra creepy factor for many who have tuned into the worldwide media coverage of real or perceived threats and crimes by those dressed as clowns.

“Coulrophobia,” the irrational fear of clowns occurs when something seems familiar but unnatural, says Gary Vaughn, UC associate professor of English, who studies the societal impact of the horror genre in television, literature and film. Some are uncomfortable with clowns, he says, because they have a familiar humanness, but at the same time their faces are covered with paint, so there is a deception.

It’s the mystique of knowing logically that there is a real person behind the painted face, red nose and giant floppy shoes, but the familiar is hidden, Vaughn says –– and things that are hidden aren’t always predictable.

Erynn Masi de Casanova, UC associate professor of sociology and author of books on the body and clothing, credits the popularity of clowns to literature and films in U.S. pop culture, citing Stephen King’s 1986 novel “It,” featuring the character Pennywise, a serial killer clown. “The successful miniseries ‘It’ left a lot of people with nightmares,” says Casanova.

Vaughn and Casanova point to anthropologist Mary Douglas who argued that changing times create an individual and cultural anxiety about the unknown. These anxieties, they say, perpetuate a fascination for creatures that exist in interstitial places –– in two realms.

Clowns can be seen in two ways, adds Vaughn. “They look human in a recognizable way and can make us laugh, yet wildly differ from ‘normal’ human appearance.

“So when we spot one in an out-of-place setting it can stop us cold in our tracks. which is why criminals take advantage of this fear.”

Mysterious clowns in film and literature were often spawned by real-life experiences such as the popular hobo clowns during the Great Depression, says Vaughn. In the 1970s, criminal John Wayne Gacy dressed as a clown for charity events and kids’ parties, but was later found to be a serial killer, murdering almost three dozen people, Vaughn adds.

In a successful attempt to twist life into art, contemporary TV character Twisty the clown from “American Horror Story: Freak Show” eventually gets revenge for bullying he had suffered at the hands of fellow circus performers, Vaughn says. This clown portrayal, he says, forces viewers to confront their own intellectual fears about difference, about diversity and about the fear of change.

While clowns have found their way into genres of drama, comedy and history, the researchers also predict a jump in the portrayal of Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton in clown-like humor this Halloween due to the widespread media lampooning of both candidates, Casanova adds.

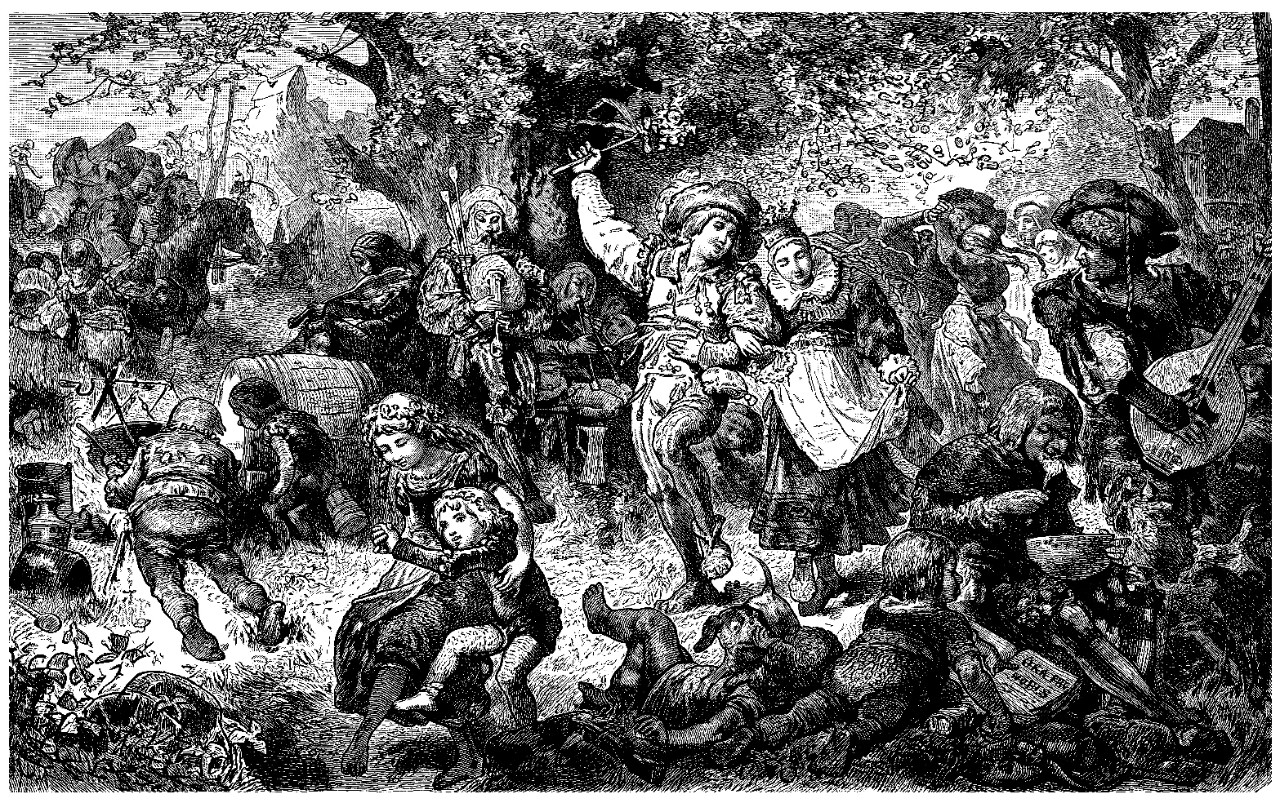

During ancient Celtic Samhain festivals people would play tricks on each other and light fires to ward off ghosts.

Halloween history

“Halloween and the resurrection of dead souls dates back to Celtic times,” says Vaughn. “ To reassure ancient farmers that their dying crops and the death seen in nature in the fall would turn around again in the spring, they developed a lot of different superstitions. This led to performing rituals like Samhain in an appeal to the spirits.

“These festivals often involved bonfires and some kind of bribery to either scare away ghosts or to placate them with offerings, eventually leading to the celebration of trick-or-treating.”

By the 19th century, Vaughn says Halloween became more of a family-friendly fun event, including traditional parties with gift giving for kids to take the “scary” out of the observance. But around the time of the Great Depression, he says economic fears brought cultural anxiety back into the picture. As an outgrowth of that, economic fears were replaced by gruesome, otherworldly fears in connection with Halloween.

Symbolic escape

Halloween characters –– ghosts, witches, monsters and the like –– Vaughn argues, rose out of hard economic times fraught with rampant disease and political turmoil. These figures representing death and feelings of helplessness are subsequently turned into a playful and cathartic release when acted out in scenarios of safe fantasy, he says.

“The thrill is both a mental and physiological phenomenon like a roller coaster ride,” he says. “The hormonal release we experience in our brains from the fear of falling or being thrown off a ride becomes exciting when at the same time we feel safe knowing we won’t be harmed –– much like those bone-chilling, yet harmless Halloween haunted houses.”

Masks and face paint in the likeness of vampires have historically risen in popularity during times of economic struggle like the Great Depression.

In the last decade zombies have gained a large cult-following and are likely to be some of the mangled faces folks see at their doors this Halloween. But beneath the surface, Vaughn says these decaying masses –– strongly represented in film and TV programs like “The Walking Dead” –– are symbols woven into the fabric of pop culture often representing economic and social factors beyond our control that eat away at our lifestyle and values.

Wanted dead and alive

“The growing popularity of zombies, monsters and ‘evil’ clowns in popular film, TV and fiction can be seen as our cultural reaction to what many people see as alarming threats, both legitimate ones like the Great Recession and perceived ones like ‘threats’ to traditional marriage and the traditional concept of ‘family,’” says Vaughn.

“Because we live in a transformative modern society that can cause a collective social angst, we often look at horror films –– and our masked dress up at Halloween –– as a way to play out the disruption of the ‘natural’ order by ‘monsters’ who create a personal and group anxiety, but is expected to eventually be relieved when the ‘monster’ is defeated and ‘normal’ order is restored.”

Faculty contributors:

- Gary Vaughn

“All the Broken and Shunned Creatures: Penny Dreadful and the Functionally Dysfunctional Family,” related research study presented in October at the 2016 Midwest Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association

A look into why the horrifying is so very intriguing