Merry Christmas, Oregon! Happy Holidays, Maine!

America divides over holiday greetings

UC political science researcher Andrew Lewis crunches newly

released data to find which regions of America prefer

“Happy Holidays” or “Merry Christmas” — and how that

corresponds to their support of President-elect Donald Trump.

by Rachel Richardson

513-556-5219

Dec. 22, 2016

President-elect Donald Trump lobbed the opening salvo in what has become an annual yuletide skirmish, the alleged “war on Christmas.”

Speaking to crowds across the nation, the Republican presidential candidate promised an end to the dreaded political correctness of the season: "If I become president, we're gonna’ be saying Merry Christmas at every store… You can leave happy holidays at the corner."

But as a political science researcher from the University of Cincinnati has found, whether a person says “Merry Christmas” or the much maligned “Happy Holidays” sometimes depends more on what part of the country one hails from than their religious leanings.

And as new data released this week indicates, the growing political divide among Americans in the wake of a contentious presidential election further polarizes the holiday debate.

Andrew Lewis, a UC assistant professor, and Paul A. Djupe, an associate professor of political science at Denison University, examined public opinion on preferences for “Merry Christmas” versus “Happy Holidays” based on data from the Public Religion Research Institute.

The PRRI surveys, conducted in 2013 and again in 2016, asked a nationally representative sample of Americans whether retailers should greet customers with “Happy Holidays” or “Season’s Greetings” rather than “Merry Christmas” out of respect for people of other faiths.

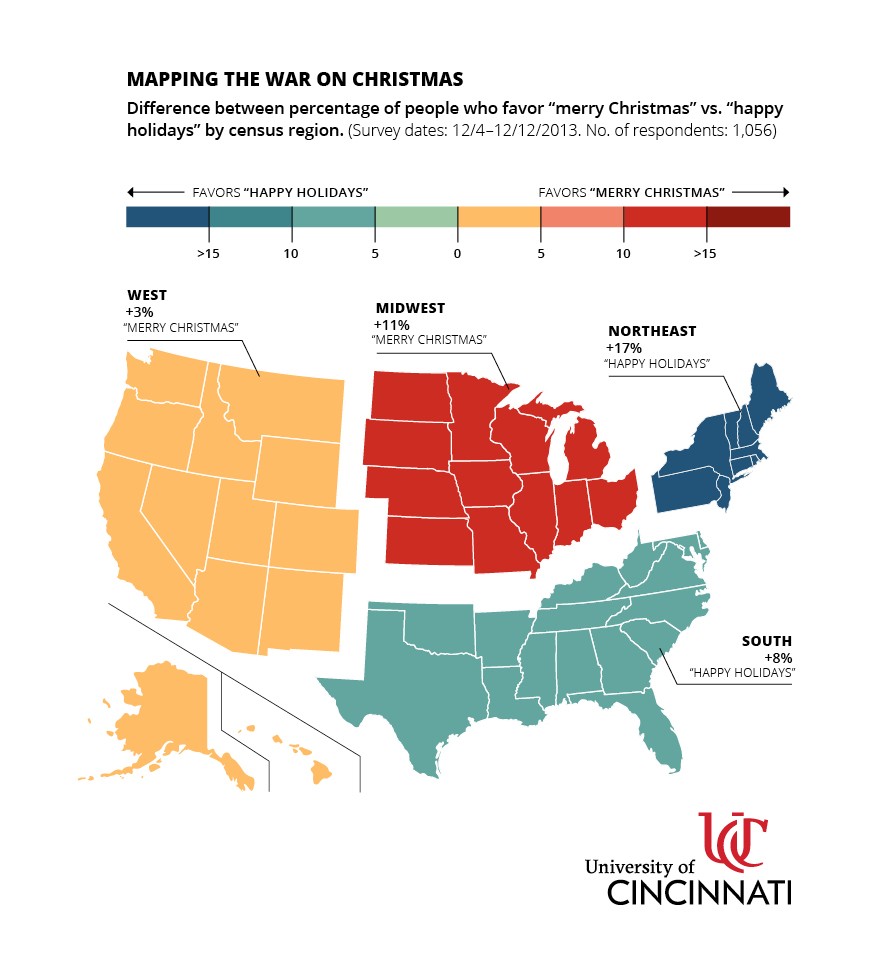

Lewis and Djupe combined data from the 2013 PRRI survey with the 2010 Religious Census to analyze how cultural tensions might affect the rhetorical ritual, and published their results last year on the website FiveThirtyEight.

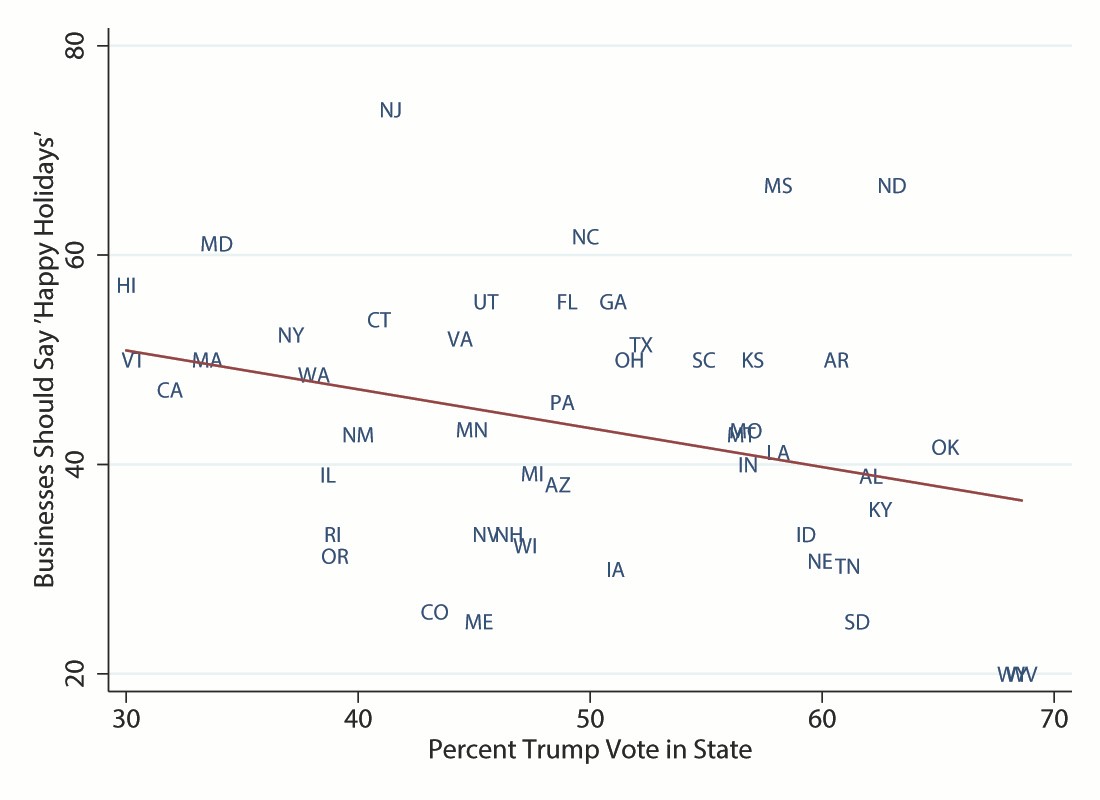

Now, the researchers have updated their findings with the 2016 survey data while adding an examination on how regional preferences for “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Holidays” corresponded to Trump’s presidential victory.

“It’s a bit of a backlash against political correctness, and this is something that Donald Trump and his campaign affiliates knew quite well,” said Lewis of the ruckus over the preferred holiday greetings.

“There were people who didn’t like a lot of this political-correctness culture and the ‘Merry Christmas’ component is one small example of this bigger narrative that has played out in this election cycle,” he said.

In analyzing the data, Lewis and Djupe found that, not surprisingly, evangelicals tend to strongly favor “Merry Christmas” while people who identify as secular prefer “Happy Holidays” or “Season’s Greetings.”

But, as the researchers also found, the ye olde “war on Christmas” isn’t simply a religious divide. Although the Bible Belt South registers as the most religious region, 54 percent of Southerners in 2013 preferred “Happy Holidays” over “Merry Christmas.”

The important distinction here, Lewis notes, is that 20 percent of the survey sample in those southern states included African-American residents, who strongly prefer “Happy Holidays” – a whopping 72 percent in 2016 – despite their high levels of religiosity.

“African-Americans are more supportive of a more inclusive ‘Happy Holidays’ greeting,” Lewis said. “We attribute that to being in the minority and extending those minority views to others who may also be in the minority.”

On average, non-Christians and the nonreligious in states with large white Christian populations are the most likely groups to urge stores to adopt a “Happy Holidays” regimen, said Lewis.

But the researchers discovered that support for “Happy Holidays” tends to drop dramatically for secular residents in largely nonreligious states, like Oregon. In 2013, western states favored “Merry Christmas” three percent higher than “Happy Holidays.”

When Christmas is more of a cultural than religious tradition, the greeting “Merry Christmas” isn’t as much of a socially and politically laden term, explains Lewis. Instead, it becomes more about presents, ugly sweaters and secular symbols like Santa.

“In low religious states, we see larger support for ‘Merry Christmas,’ but it’s not a religious support,” said Lewis. “When Christmas is more cultural than religious in one’s state, they prefer ‘Merry Christmas.’”

A preference for “Merry Christmas” is also a political statement, the researchers found. Republicans oppose “Happy Holidays” at the strongest rates and most consistently across the nation, they found. Indeed, in 2013, Republicans as a whole (70 percent) outpaced even evangelical Republicans (62 percent) in their support for saying “Merry Christmas.”

However, opposition to “Happy Holidays” amongst evangelicals is growing. In 2016, only 22 percent of evangelical Republicans preferred “Happy Holidays,” compared to 35 percent of non-evangelical Republicans.

The region with the strongest support for “Merry Christmas?” The Midwest, with 58 percent of residents in 2016 expressing a preference for the more religious greeting.

It’s here, where people are more staunchly opposed to “Happy Holidays,” that party preference proves the sharpest dividing line, said Lewis, noting that the Midwest is where Trump outperformed his polling numbers.

“Electorally, Trump outperformed in the Midwest, the exact region where support for ‘Merry Christmas’ is the highest,” Lewis explains. “While likely not causal, the ‘war on Christmas’ is instructive of the cultural divide that was key to the 2016 election.”

Trump’s emphasis on cultural threats in his appeals to white working class voters and white evangelicals resonated strongly in these largely white Midwestern states, said Lewis. This, he explained, may have contributed to a backlash among Democrats and secular people – who are more concentrated in Western states – resulting in this region increasing its support for “Happy Holidays” from 49 percent in 2013 to 55 percent in 2016.

While the data indicates there is no orchestrated or national war against saying “Merry Christmas,” Lewis said that it’s important to recognize that many people view Christmas and its associated greetings as a broader symbol reflecting intergroup tensions and changing cultural values.

“It’s not a real ‘war on Christmas,’ but there are competing ways in which people discuss it,” he said. “There is certainly a divide in American culture on how we’re going to balance our changing demographics, religious faiths and political values.”

And despite national calls for boycotts on companies accused of “censoring Christmas” or not promoting Jesus enough on holiday cups, Lewis notes that the uproar is mostly the blustering of a small segment of the population.

“Most people aren’t generally outraged by these things,” he said. “They may prefer one way or another, but it doesn’t get them that worked up.”