Jacqueline Lawson enjoys the sun and fountains at Washington Park. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Creative Services

[Homeless] kids will be kids

UC professor takes on childhood homelessness one child at a time

by Jessica Noll

513-556-5224

Photos by Joseph Fuqua II

July 6, 2017

Jacqueline Lawson, a fifth-grader from Newport, Kentucky, laughs and squeals as her water-soaked cousin hugs her and picks her up, drenching her too. With the sun beating down, it’s a scorcher, so she kicks off her wedged shoes, hikes up her summer turquoise dress and splashes in the Washington Park fountain with several others. Kids being kids.

It's Lawson’s first summer camp ever, and she’s loving every minute.

“[I like] all the places we go, and everyone’s so nice,” says the blonde with a summer-kissed tan, reminiscing about their trip to a waterpark where she floated down the lazy river.

Lawson, 10, is one of 65 homeless kids enjoying a muggy July day with an ice cream social in Over-the-Rhine with UpSpring, a nonprofit in Cincinnati that caters solely to homeless children. While we caught up with these kids in the summer of 2016, this summer represents UpSpring's 10th summer camp.

Joli Martin enjoys her ice cream at Washington Park. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Creative Services

Nearby, 8-year-old Joli Martin, of the Cincinnati neighborhood Linwood, is slurping a cup full of Neapolitan ice cream, trying desperately not to get brain freeze. While blue-moo cookie dough is her preference, she eagerly admits today’s choice is, “really good!”

The third-grader loves summertime. “I can be free, go outside and jump rope or do cartwheels.”

But her favorite thing is cooking.

“I want to be a chef,” she says, boasting that she prepares dinner for her family, including her six brothers and sisters. Her best meal to cook is potatoes, chicken breasts and Brussels sprouts.

UpSpring summer camper enjoys the sun and fun at Washington Park.

The two kids were asked to join in a special project for James Canfield, an assistant professor in the University of Cincinnati’s School of Social Work who is UpSpring’s lead researcher.

As part of his partnership with UpSpring, and using funds from a small community health grant from the Center for Clinical & Translational Science & Training, they implemented Photovoice as a camp project.

The summer campers were asked two question: “What happens when you get sick?” and “Where do you go when you are sick?”

He gave them cameras, and they took photos that showcased their answers.

Martin took a photo of herself wrapped up in a cover on the couch, not smiling to show what happens to her when she’s not feeling well. And while she had a photo of the hospital that she accidentally deleted, she took a photo of the medicine she would take.

Lawson (who admittedly took a ton of selfies after she was done with her photo project) photographed herself laying in bed with her eyes closed and a photo of her drawing that showed her house. She also captured a photo of herself drinking a can of chicken noodle soup because that’s what makes her feel better when she’s sick.

Dr. James Canfield/Provided

From there, campers discussed the pictures and their meaning — in turn, giving the kids’ perspective about health disparities and giving them a voice to their process for pursuing health care.

“It allows them, in their own voice, to describe their existence. Much of the literature is void of their voices,” says Canfield about the Photovoice project and why it’s so imperative to include it in his next book.

Canfield’s research with UpSpring has allowed him to not only contribute to national statistics, but also produce local numbers for publication and UpSpring.

“James’ research enables organizations like ours to keep track of our progress and identify areas for improvement,” says Mike Moroski, UpSpring’s director. “Without James’ dedication to improving educational outcomes for children experiencing homelessness, organizations like UpSpring would do things ‘just because.’”

Instead, he says, they are able to do things intentionally, knowing why they are doing what they are doing. And, Canfield helps them to craft the “why.”

Jacqueline Lawson enjoys the sun and fountains at Washington Park. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Creative Services

Fighting the good fight

Since opening its doors in 1998, UpSpring has worked with more than 40,000 children experiencing homelessness, says Moroski. Each year the organization empowers the lives of nearly 3,000 children experiencing homelessness in the Tristate, he says.

“I don’t know how to do anything other than fight for those who are too often overlooked. It’s literally in my DNA. These kids need some love, and I was afforded numerous blessings that enable me to serve as a bridge to the love they need,” Moroski adds.

He believes that the homeless kids whom he works with need a system that promotes good behavior to be successful.

“We reward greed in our country as if it were a virtue. We do not reward struggle and perseverance. We do not reward those who work hard for a little piece of the pie,” says Moroski. “No, we let them have their little piece and take the crust away before they can finish.”

The U.S. is not one of “opportunity for all,” and that’s why the work he and Canfield do is so important, he says. But most importantly, he wants kids, homeless or not, to just be allowed to be kids.

When you do, he continues, it impacts their social and emotional intelligence positively. Simply put, kids cannot learn and be successful if they are not allowed to be kids.

UpSpring summer campers, Kenton M., Joli Martin and Jaslene R., enjoy the sun and fun at Washington Park. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Creative Services

A life’s work

Canfield is a 32-year-old, no-bull social work professor who Tweets, Snapchats and is on Instagram as the “Millennial Professor.”

After his 2003 graduation from Cincinnati’s Lakota East High School, the whiz kid went on to earn his bachelor’s, master’s and doctorate in social work within eight years at Florida State University. And after two years at Northern Kentucky University for postdoctoral work, he landed at UC in 2014.

His self-proclaimed, yet aptly deserved, “young arrogance” is plated with a side of humble pie.

Modest despite his many accolades and accomplishments, he doesn’t think he’s changing the world — especially when there are still children starving on the streets every single day, he says.

But, Canfield also doesn’t like to take himself too seriously.

“I work with homeless kids. If you take yourself too seriously, you’re either going to become this terrible human being who sees nothing but just misery all around you, or you curl up in a ball and cry. So you have to have a certain level of both humor and self-deprecation.”

But kids, he says, can see who you are, and they know when you’re lying to them.

“You don’t have to be cool around kids. You just have to be yourself. Kids have always seen me as honest.” Even if that means they see him as a “dork.”

Being himself, dork or not, has instead given him the upper hand.

“I like to speak up a lot. I like to talk about things that make people uncomfortable.” It’s those characteristics about himself that, once upon a time, he wished he could’ve changed about himself. Now, however, it’s those attributes that make him a successful academic in sociology, he says. He’s learned to embrace his shortcomings to excel in what he does.

It was nearly a decade ago, while he was working at an internship with a transitional housing facility, that he had his “aha” moment.

One Thursday in 2007, Canfield was put on “babysitting duty” while kids’ parents were getting the information that they needed for referrals at the shelter.

That day, just one family came inside. “Finding Nemo” was on TV, which seemed to easily occupy the family’s 8-year-old twin girls. But then the movie ended. And he couldn’t find the remote. Pressing play over and over and over wasn’t cutting it.

Panic set in for the then 23-year-old Canfield.

Finally, after listening to the incessant Dory character repeating, “Press play!” on a loop during the movie’s intro screen for what seemed like forever, he shut off the TV and handed the girls coloring books. But all the pages had been colored. The twins got a mischievous grin on their faces and started looking at the copy machine — the sacred item of the shelter that he was sworn to protect with his life. So, he opted to offer them a game. He suggested Scrambles, where he would mix up letters and they would try to guess what the word is.

They rocked the game.

They were easily getting words like, ball and boat. As he started ramping up the difficulty, they were guessing the words before he was done writing all of the letters. They asked him for a really hard word.

“You want a hard word?”

“Yea!” they said, in what he calls that creepy unison that only twins can pull off.

So, he gave them “zygomorphic” thinking that would give them something to mull over for a while.

Dr. James Canfield/Provided

Ten minutes later, they unscrambled the word he was sure would stump them.

They explained.

“Morph is a real word. ‘I-C’ usually comes at the end of words, and we’ve never seen ‘Z’ and ‘G’ next to each other.”

From that they narrowed the choices down to four and went with: zygomorphic.

“What’s it mean?” they asked him.

He had no idea, having only read it in a “Calvin and Hobbes” cartoon once. Together, the three looked it up online and discovered that it meant something that has bilateral symmetry. From that point on, he stopped looking at them as an annoyance, but instead started talking to them — asking them, what he presumed was an innocuous question.

“What do you want to be when you grow up?”

“We want to be a worker.”

He figured that they meant social worker, since he knows that they’ve been around them a lot and that they make a difference. But one chimed in, “No, a worker at Winn Dixie.” The other said, “No, Home Depot. It pays more.”

While he notes that there’s nothing wrong with those jobs, Canfield says, “These were 8-year-old girls who unscrambled the word ‘zygomorphic’ — and their big dream, their big life goal, that thing that drove them was to work at Home Depot or Lowes because it paid more than Winn Dixie. And that always bothered me. You have kids who don’t even know how brilliant they are walking around on this Earth.”

After picking his jaw up off the floor, he told them that the world was theirs, and they could be anything they wanted. Reflecting on that moment years later, he says, they couldn’t be whatever they want because of their situation.

“They’re more concerned with hunger than homework, standing in a shelter line than studying shapes, and just surviving until tomorrow. And that never sat well with me.”

UpSpring summer camper enjoys the sun and fun at Washington Park. Photo/Joe Fuqua/UC Creative Services

Uncloaking the invisible

His first book, he jokes, is the “greatest book ever written on children experiencing homelessness … because it’s one of the few that’s ever been written.”

The Oxford University Press published “School-based Practice with Children and Youth Experiencing Homelessness” in 2015, which is based on Canfield’s own experiences working with homeless children and includes academic literature in his dissertation.

“The place where homeless kids, compared to homeless adults, really intersect with any sort of interventions are often within the school,” he says. The book addresses how schools can work with children who are homeless — and it was based on Canfield’s own experiences.

His next book, which is currently underway, will explore the invisible struggle of homeless kids making it day to day — growing up while in the process of being homeless.

In the book, he questions what someone typically thinks when they think of homelessness.

“You think of that dude with the cardboard sign off the highway exit, and you don’t want to make eye contact, so you start fumbling with your radio… or it’s that person with that half-empty bottle of malt liquor in a cardboard box, passed out midday. Or it’s the bag lady stuck like a homeless Sisyphus, forever pushing a cart.”

Maybe those are the stereotypes you envision, but he says, 40 percent of the homeless are children and families.

“And it’s an invisible struggle they have — this sort of unseen existence.”

Canfield says everyone should remember two things:

1. We’re all in it together.

2. Treat people like people.

“You’re a person, first and foremost, and we’re going to treat you like you’re human. If you treat kids like kids, they’ll be successful. People always act how you think they’re going to act. If you expect a kid to be a thug, you’re going to get a thug.”

He says when he looks at his own success, it’s a struggle.

“By a lot of measures, I’ve had a lot of success and by a lot of people’s metrics I’m a very successful professor.”

He’s done TV, radio, TED talks and had countless stories done on him for print news. He’s an accomplished researcher, professor and author.

“But at the end of the day, that was all yesterday. I always feel that reminiscing is very dangerous. There are still kids sleeping on the street. There will be a kid that will die tonight because of it.

“Somewhere in America, there is a kid who’s going to starve to death. Somewhere in America, there is a kid who’s terrified about what’s going to happen next. So, you know what? There’s still work to do.”

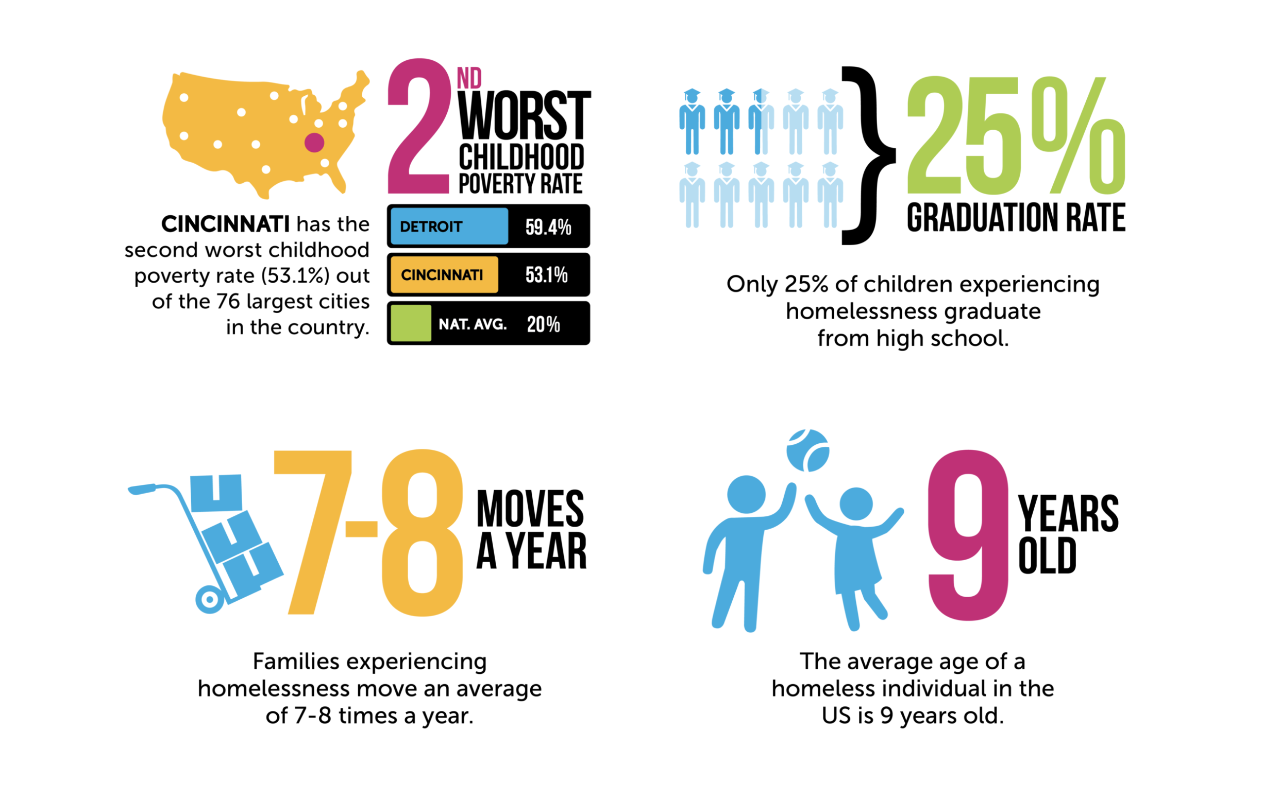

Homelessness by the numbers

- The average age of any homeless person in the U.S. is 9 years old.

- Cincinnati has the second worst childhood poverty rate, at 53 percent, out of the 76 largest cities in the country, only second to Detroit at 59 percent. The national average is 20 percent.

- Only 25 percent of homeless children will graduate from high school.

- Homeless families will move more than a half a dozen times every year.

- On average, there are 7,000 children who experience homelessness in Greater Cincinnati each year.

- Kentucky has the worst childhood homelessness rate in the country.

- The average type of family experiencing homelessness locally: single mother age 30 with two kids under 6.

- Children experiencing homelessness are typically two to three years behind in school.

— Source: UpSpring

— Jessica Noll is a former public information officer with UC. This story was largely written and photographed in the summer of 2016.