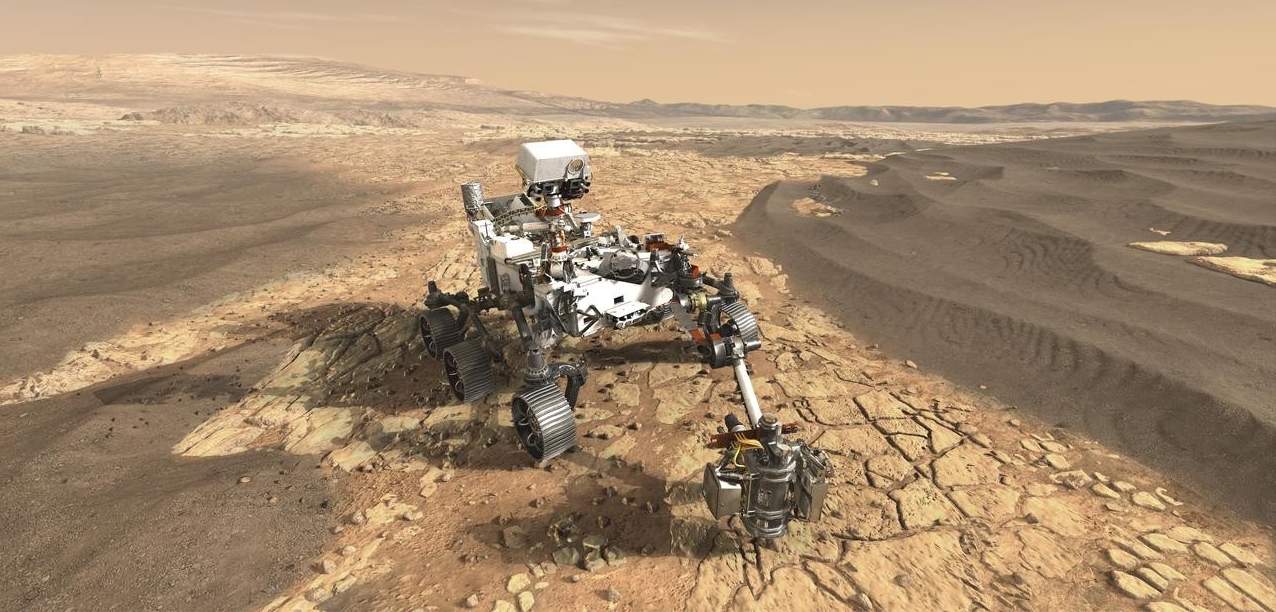

An artist's rendering of NASA's next Mars rover which is scheduled to launch in 2020. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Mars or bust

UC's Andrew Czaja teams with NASA to decide where to send the next rover to look for ancient life on Mars.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

June 22, 2017

A University of Cincinnati geology professor is helping NASA answer one of science’s biggest questions: Is there life on other planets?

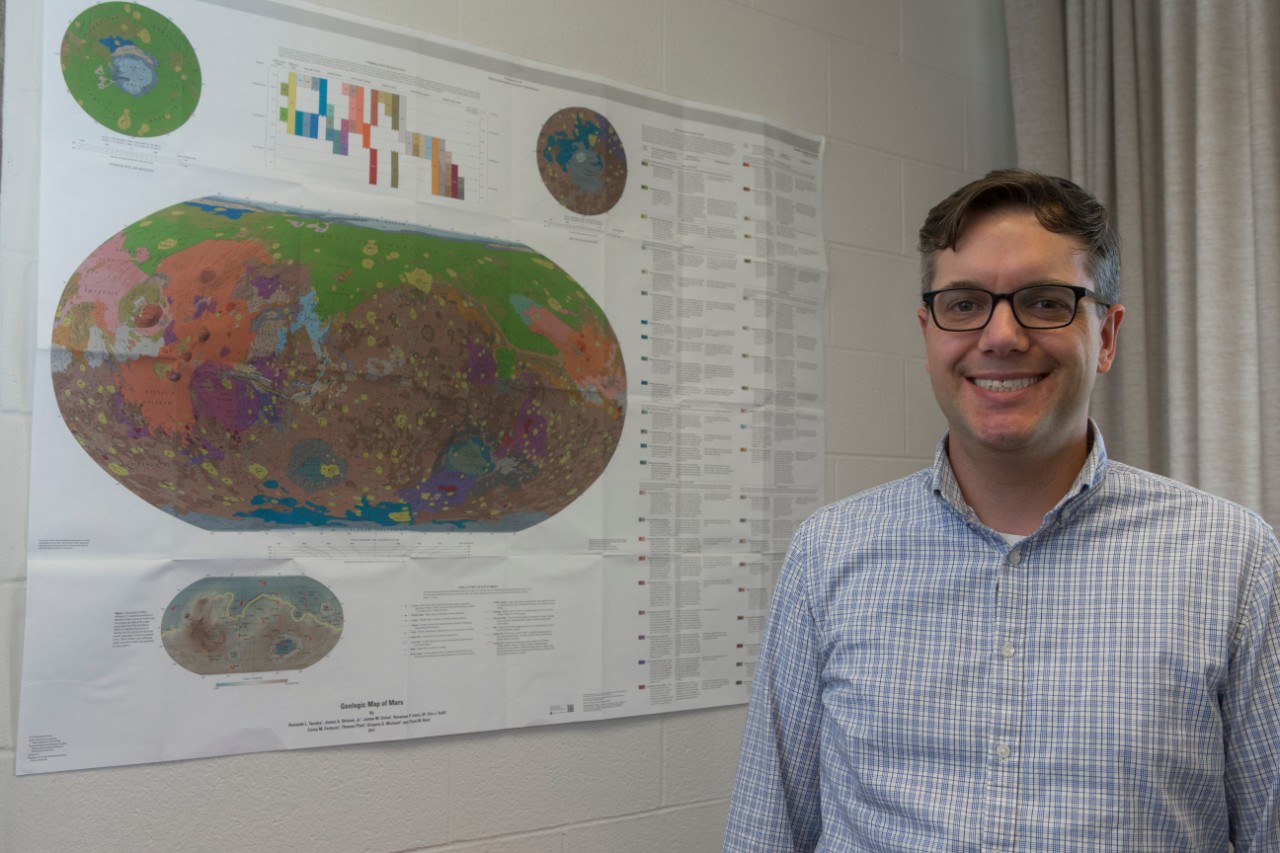

Andrew Czaja, a Precambrian paleobiologist and astrobiologist, will help decide where on Mars to land NASA’s most sophisticated rover to date. Czaja is a member of the Returned Sample Science Board, which NASA created to help plan the Mars 2020 mission. NASA wants to collect rock samples that prove once and for all that a planet other than Earth sustained life. The board has helped narrow the potential landing sites from 30 to eight to just three.

“I’m of the opinion that if life ever existed on Mars, it’s still there,” said Czaja, an assistant professor in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

“Killing all the bacteria on a planet is very difficult. If any of them survive, they could reproduce and evolve very quickly, adapting to new conditions," he said.

Czaja has always been interested in space. As a graduate student, he was a member of the NASA Astrobiology Institute. When he was invited to join the Mars 2020 science board in 2015, he jumped at the chance.

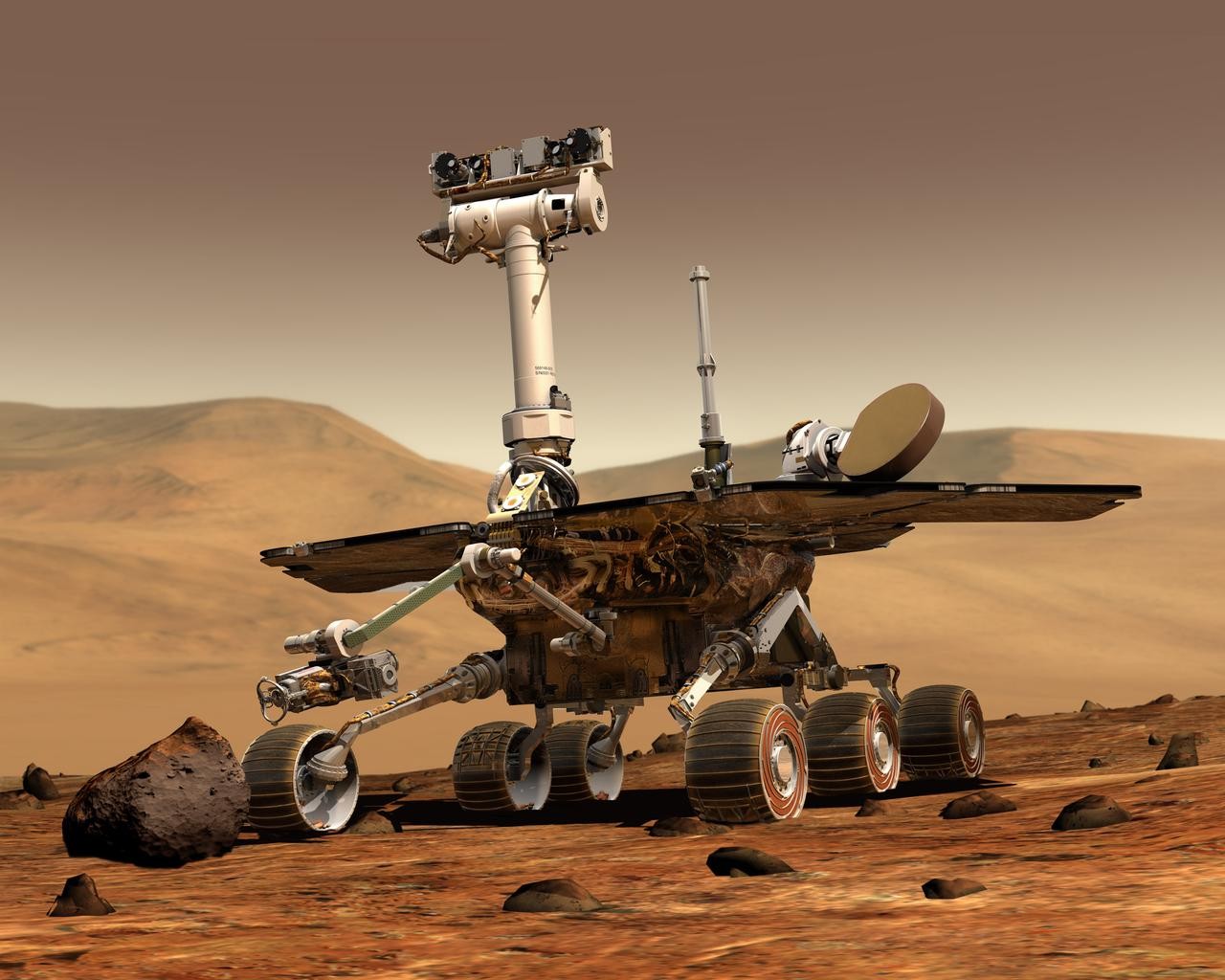

Scientists still have much to learn about the Red Planet since taking the first photos of its surface from orbit in 1965. Several landers and four rovers have explored Mars, albeit a tiny fraction of it. This includes Sojourner, the rover featured in the sci-fi movie, “The Martian,” and the still-functional rovers Opportunity and Curiosity. A counterpart of Opportunity called Spirit launched in 2003, got stuck in soft sand in 2009 and ended its mission two years later.

UC geology professor Andrew Czaja said scientists will look for signs of layering or sedimentation in Martian rocks that are evidence of ancient bacterial life.

For Mars 2020, the Jet Propulsion Laboratory is building its most sophisticated rover yet, said Ken Williford, deputy project scientist for NASA. The new Mars 2020 rover looks like Pixar’s WALL-E. It has an array of scientific instruments and cameras mounted on a flat six-wheeled platform the size of a golf cart to assess the geology and natural resources it encounters. And unlike other rovers, it will have microphones to record and broadcast the ambient sounds of Mars.

The rover will look for potential hazards to human exploration, collect rock samples and try to extract oxygen from the atmosphere. Its work is a prelude to a manned mission to Mars envisioned in about 20 years. NASA aims to launch the rover from a rocket at Cape Canaveral, Florida, in 2020.

NASA increases its odds of success with each mission by relying on parts or procedures that have worked in the past. They call this “flight heritage.”

“We build a rover that looks almost identical to Curiosity but has important improvements and a new scientific payload,” he said.

The new rover will have specialized tools that will give the mission its best chance yet to determine if Mars ever sustained microbial life. It’s the next step in a progression of missions that so far have established that Mars had liquid water and habitable environments.

“In this mission, we’re taking the next step by directly seeking signs of ancient life,” Williford said. “It’s a big adventure. We don’t know what we’ll find.”

Secondary objectives are to study the Martian surface for anything potentially toxic to humans and to demonstrate it’s possible to harvest oxygen from the atmosphere, he said.

Mars is only half the size of Earth but with no oceans or lakes has nearly the same amount of land area to explore. Choosing the best site is key to success. Scientists want to go where they will have the best chance of finding a fossil record, Czaja said.

“It’s like a historian going back and looking for ancient scrolls. If the library burned down like in Alexandria, it’s lost,” Czaja said. “It’s the same with rocks. If they get eroded or otherwise destroyed, fossil evidence in them is lost.”

The farther back in time you look, the fewer rocks you find, he said.

“Rocks are constantly being formed and eroded and destroyed,” Czaja said. “The rock record is the only place we have evidence of ancient life on Earth.”

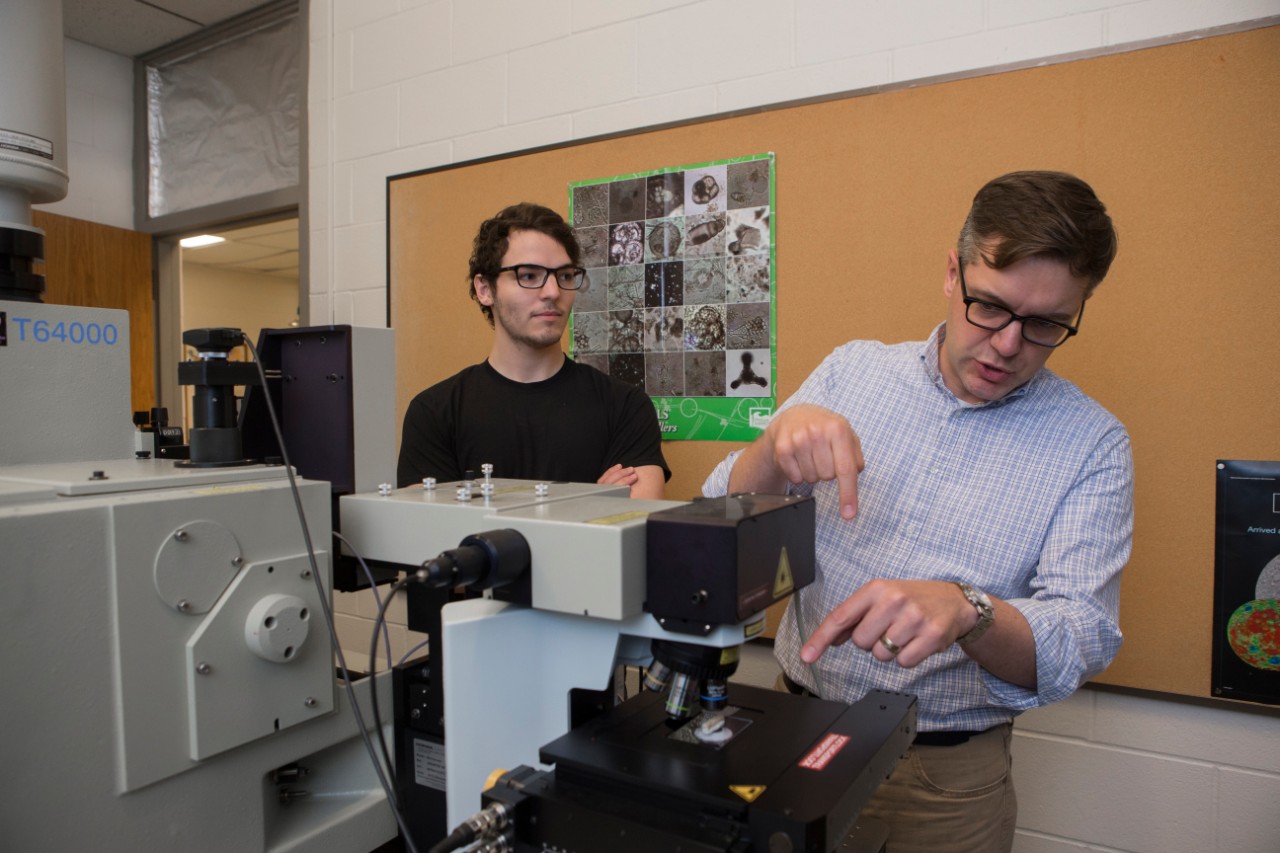

UC geology professor Andrew Czaja, right, and graduate student Andrew Gangidine use a spectroscopy machine in Czaja's lab.

After months of debate, three landing sites remain under consideration:

• Columbia Hills, the site explored by the Spirit rover between 2003 and 2011 and named for the seven astronauts killed aboard the space shuttle Columbia.

• Northeast Syrtis, a region where there is apparent evidence of hydrothermal deposits.

• Jezero Crater, the site of what might be an ancient river delta, which could harbor fossil evidence of past life.

The decision poses a dilemma for researchers: return to a place NASA knows pretty well already or venture out to explore brave, new territory.

Czaja sees merit in both arguments. He has not made up his mind which of the three is best.

"Are we alone in the universe? The question has been a recurring one for mankind. Now NASA has the means and funding to answer it."

‒ UC graduate student Andrew Gangidine

“At Columbia Hills we want to sample these silica deposits that might trap organic molecules or they might trap textures like ministromatolites,” he said.

Stromatolites are fossils found in some of Earth’s oldest rocks dating back billions of years. They have wrinkled ridges that suggest they were once covered in sticky mats of bacteria upon which additional sediment adhered.

“Finding something like this on Mars would be amazing,” he said.

On the other hand, Jezero Crater might hold the best chance of retaining fossils, he said.

“It’s like a river delta system with a branching pattern of channels stretching out into the ocean. This is a great place on Earth to look for evidence of past life,” he said. “Any biological material being transported downstream gets deposited at the ends of these deltas.”

Czaja also embraces the spirit of adventure that comes with exploring a place never before seen by human eyes.

“We’ve been very few places on Mars — just four rovers and a few landers,” he said. “There are lots of places to explore. Every time we go somewhere new, we learn something unexpected.”

Ironically, NASA is avoiding places most likely to harbor existing life on Mars to reduce the possibility of contaminating the planet with invasive life from Earth. Instead, they will look for fossil evidence of life that existed billions of years ago.

The rover will scout for and collect the most likely specimens with the goal of bringing back the first Martian souvenirs in a future mission. NASA opted to perform this ambitious goal in stages to improve the likelihood of success, Czaja said.

But first they have to find something to justify the effort, he said.

“We want to bring samples back because we have access here to every instrument that exists, including instruments that don’t exist yet or that will be more sophisticated in the future,” he said.

By comparison, the rover’s instruments are small and less sensitive — a necessary trade-off in shipping a mobile self-contained laboratory 34 million miles away.

UC already has an indelible connection to Mars. According to NASA, UC astronomer Ormsby McKnight Mitchel in 1846 used a telescope at the observatory he founded in Cincinnati to record lingering frost on a geographical feature in Mars' southern hemisphere. He surmised they must be mountains.

The Mars Global Surveyor, launched in 1996, studied the area and determined that they were not mountains, exactly, but highlands in which the southern face was shaded from the spring sun and retained annual frost later in the year than other parts of the icecap.

Regardless, this geographic feature is now known as the Mountains of Mitchel, after the UC astronomer.

An artist's rendering of Opportunity, one of two rovers launched in 2003 to explore Mars. (NASA/JPL/Cornell University)

The rover will store the samples for safekeeping, probably somewhere shady like next to a boulder, Czaja said. The surface temperature ranges from subfreezing to 70 degrees Fahrenheit during the Martian summer. The metal sample tubes will be subjected to periods of freezing and thawing while awaiting their return to Earth.

Likewise, the sample tubes are designed to stay sealed to prevent contamination during storage and transit back to Earth until NASA is ready to open them.

NASA is determined to prevent any Earth bacteria from reaching Mars, which is tricky when it comes to sterilizing a rover loaded with electronics and lots of tiny moving parts.

Czaja said he hopes to contribute to the science team when the rover reaches the Red Planet in 2021. And it could be many years or decades before he and other geologists get to see Martian samples with their own eyes back on Earth.

In the meantime, he is sharing his work with his students who are equally intrigued by the possibilities. UC graduate student Andrew Gangidine hopes to incorporate the ongoing NASA mission into his own geology career. As part of his thesis, he attended the Mars 2020 board’s landing-site workshops with Czaja. The mission is fraught with technical challenges. But it gets at a fundamental scientific pursuit, Gangidine said.

“Are we alone in the universe? The question has been a recurring one for mankind. Now NASA has the means and funding to answer it,” he said.

That answer has the potential to change the way people think about the universe and our place in it. So it is crucial to have utter confidence in the results, he said.

“Just because it looks like life doesn’t mean it is life. There is going to be a huge burden of proof if we find something that looks like life,” Gangidine said.

And Czaja said the Mars project is bound to captivate his students for years to come.

“I’ll probably be pretty far along in my career when the samples come back. It’s my students who will be studying these samples,” he said. “We have to think long term with this.”

UC geology professor Andrew Czaja in front of a map of Mars in his office.

Fermi’s Paradox

One nagging question about extraterrestrial life has puzzled scientists such as the late Italian physicist Enrico Fermi. It’s called Fermi’s paradox: Given the strong likelihood of intelligent life in the universe, why haven’t we found evidence of it? University of Cincinnati geology professor Andrew Czaja offers his explanation:

"We’ve only been able to transmit signals for the last 100 years. So in terms of other planets knowing about us, they’d have to be within 100 light years to detect a signal from Earth. One-hundred light years isn’t that far. It may be there is no intelligent life within that range — or maybe there is, and they just detected us 10 years ago, and they haven’t been able to send us a signal. Or maybe intelligent beings visited Earth a million years ago. We weren’t even human beings yet.

"It’s tough to wrap our heads around the vast distances and timescales of the universe. I have a hard time with it and I think about it a lot. It’s something I try to get my students to think about. We’re used to seconds and minutes and hours and days and months and years. But that’s nothing."

About Mars:

Fourth planet from the sun.

Martian days are a half-hour longer than Earth's.

Martian years take 687 Earth days.

Has two moons, Phobos and Deimos.

Mars Exploration:

1971 — Soviet Union deploys first lander.

1997 — NASA’s Pathfinder deploys Sojourner rover to explore.

2004 — NASA deploys twin rovers Spirit and Opportunity.

2012 — NASA deploys one-ton Curiosity rover.

2021 — NASA to deploy new sample-collecting rover.

Source: NASA/JPL

UC in the news

Listen to UC geology professor Andrew Czaja and graduate student Andrew Gangidine talk about NASA's next rover mission to Mars on WVXU's "Cincinnati Edition."

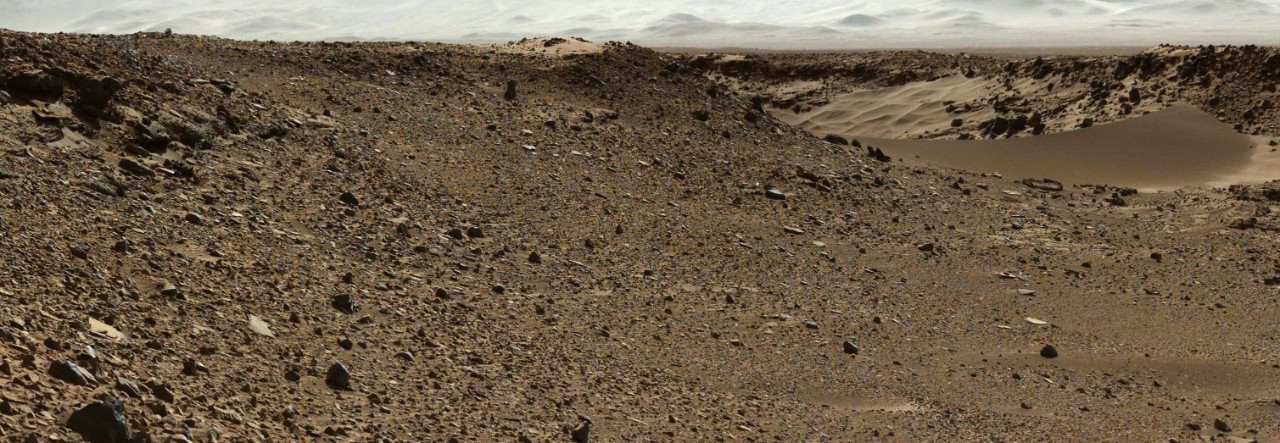

NASA's Spirit rover takes a photo showing its path across the Martian landscape on Sol 1806 or nearly three years into its mission. One of its wheels malfunctioned, apparent in the treadmarks. (NASA/JPL-Caltech)

NASA's Curiosity rover captured this landscape shot of Mars in 2014. (NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS)

Boldly go where no one has gone before

Do you have an adventurous spirit? At UC, geology students use the latest techniques to explore the universe. Apply to the Department of Geology or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.