UC graduate student Samuel Garvey stands in front of a cast of a mosasaur skull that UC's Department of Biological Sciences acquired this year.

Latest Magazine

September 2018

September 2018

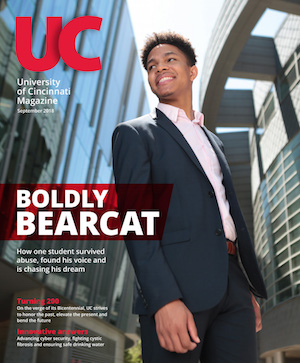

Boldly Bearcat

Finding his voice

Danger in the tap

Virtual defense

Global game changer

Celebrating UC's Bicentennial

Past Issues

Past Issues

Browse our archive of UC Magazine past issues.

'Big bads of the Cretaceous'

Ancient mosasaurs ate most anything they could catch. But UC paleontologist Takuya Konishi thinks one newly discovered species might have specialized in fish.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Ravenna Rutledge/UC Creative Services

April 5, 2018

Takuya Konishi held up a fossil of a mosasaur, a ferocious marine reptile that lived alongside dinosaurs more than 65 million years ago.

The wishbone-shaped lower jawbone didn’t look like much, but to Konishi it was a fantastic clue.

“Here is what I think is a new kind of mosasaur,” said Konishi, an assistant professor of biological sciences at the University of Cincinnati. “I can say that from ‘only’ this much bone. But only is in quotation marks. This is a very good specimen.”

With 18 peer-reviewed journal articles on the subject, Konishi is an internationally renowned expert on mosasaurs, the aquatic predator and unlikely hero of the 2015 blockbuster movie “Jurassic World.”

The paleontologist in UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences has spent much of his career piecing together the lives of these predators that lived alongside Tyrannosaurus rex.

While visitors to museums see complete fossil skeletons of mosasaurs suspended in dramatic hunting postures, paleontologists more typically find a dull-colored fragment like the one Konishi held. Piece together enough of these fragments and the fossils begin to tell a story, he said.

“We’re not dealing with ‘Jurassic World,’” Konishi said. “It’s a lot of detective work. That is the great appeal of paleontology. We’re so limited with the evidence so it’s our points of view we should sharpen and hone so we can shed new light on the discoveries.”

A fossilized mosasaur found in Kansas in 1991 is suspended from the ceiling of UC's Geology-Physics Building where it is on public display.

About 70 species of mosasaur have been identified so far. Some were as small as dolphins while others were bigger than Greyhound buses.

Mosasaurs are more closely related to snakes and lizards than dinosaurs. While mosasaurs went extinct 65 million years ago, other marine reptiles from that time, such as sea turtles, persisted. By learning more about mosasaurs, we can understand evolutionary processes such as extinction that influence species today, Konishi said.

“Superficially, mosasaurs look like the T. rex of the sea,” he said. “They were apex predators, like killer whales today. They were bigger than the sharks of their time. They occupied every niche available to them.”

Mosasaurs have a lot in common with today’s monitor lizards, except they were true marine reptiles that never left the water and gave birth to live young. They were found off the coasts of every continent and dominated their marine habitats for about 30 million years. Scientists have identified about 70 species ranging in size from a bottlenose dolphin to a Greyhound bus.

And most of what is known about mosasaurs was pieced together from small bits of fossil collected and examined by paleontologists over the past 200 years.

“Every now and then you strike a gold mine and find something like this,” Konishi said, holding up the intact jawbone. “You always have to be working on these less-optimal specimens so you can maximize the scientific value of the more complete specimens when they are discovered.”

UC researchers study mosasaur teeth, among other clues, to learn more about their likely prey.

One recently discovered fossil, in particular, has captured the attention of Konishi and UC graduate student Samuel Garvey. It is one of the larger of known kinds of mosasaur called a tylosaur and was unearthed around Grande Prairie, Alberta, Canada, in what used to be a vast inland sea.

“In the time of Tyrannosaurus and his geologically older cousin Albertosaurus, the Western Interior Seaway stretched from what is now the Arctic Ocean all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico through the heart of North America,” Konishi said.

Garvey is working on a quantitative model for interpreting both the preferred prey and the function of predator teeth based on their shape and variety. Mosasaurs are good models for this analysis since different species have unique dentition.

“They were apex predators. They were the big bads of the Cretaceous sea,” Garvey said. “There are unique things about my specimen. So are there other high-latitude specimens that might show similar characteristics? Or is it anomalous?”

“There are still many things from basic taxonomy to physiology to paleobiological questions we have about mosasaurs.”

‒ Takuya Konishi, UC assistant professor of biological sciences

UC paleontologist Takuya Konishi poses with an ammonite fossil he discovered in Alberta, Canada, in 2011. (Photo by Darren Tanke/Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology)

What is most striking about Garvey’s 20-foot-long tylosaur, Konishi said, is its sharp but slender teeth.

Scientists think mosasaurs were opportunistic predators, hunting and eating most anything they could catch based on the fossilized stomach contents found in some specimens. Most had ferocious jaws and teeth that would have made them effective hunters of everything from sea turtles and hard-shelled squid to smaller mosasaurs, Konishi said.

“It’s not that surprising, knowing how robust their teeth are,” Konishi said. “They could eat almost anything. They didn’t have to be choosy.”

These conical teeth were durable, capable of crushing shell or digging into bone. The teeth of many specimens were worn, suggesting they got plenty of use biting into hard prey. And like sharks, they grew new teeth to replace older ones throughout their lives.

But the sharp, slender teeth in the mosasaur Garvey is studying probably wouldn’t have been able to tackle such hard prey, Konishi said.

“That suggests that it was eating something different — most likely fish,” he said.

UC student Samuel Garvey peers up at a fossilized mosasaur on display in UC's Geology-Physics Building.

If these mosasaurs primarily survived on fish, it’s possible they could have lived alongside the generalist mosasaurs without the pressure of competition.

“How would you have two big predators in the same ecosystem without losing one from competition or natural selection? They probably relied on different prey,” Konishi said.

Like snakes, mosasaurs also had a second row of dentition on the roof of their mouths called pterygoid teeth. Konishi said these would have helped mosasaurs grip and swallow slippery prey such as fish without also swallowing seawater.

Marine reptiles have novel ways of processing salt from the food and water they consume. While mammals can process and eliminate salt through their urine, reptiles typically have glands that help them expel it. Sea turtles have glands behind their tear ducts so they ‘cry’ to expel salt. Sea snakes have glands in their mouth, he said.

“Every time they flick their tongue, they remove salt. And marine iguanas sneeze out the salt,” Konishi said.

Konishi said mosasaurs likely had salt glands as well to survive in their marine environment. These adaptations enabled lizards to colonize virtually every warm habitat on Earth.

“There are still many things from basic taxonomy to physiology to paleobiological questions we have about mosasaurs,” Konishi said.

“If you go out in the field there, you will find something. You always find something. And with that comes new discoveries.”

‒ Takuya Konishi, UC paleontologist

UC graduate student Samuel Garvey examines a cast of a mosasaur skull.

UC biology professor Takuya Konishi said mosasaurs were more closely related to lizards such as this Nile monitor than they were to dinosaurs. (Photo by Michael Miller)

UC professor Takuya Konishi in 2011 discovered the largest fossilized ammonite shell ever found in Alberta, Canada, while working at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology.

Paleontologists have found a treasure trove of mosasaur fossils in parts of Kansas and Alberta, Canada, that were underwater more than 80 million years ago.

One of these hotbeds is Hays, Kansas, home to Fort Hays State University’s Sternberg Museum of Natural History. It was named for the Sternberg family, including George F. Sternberg, one of the first settlers to discover mosasaur fossils in Kansas after the Civil War, and his son Charles Sternberg, one of the museum’s first curators.

Konishi spends a fair amount of his time fossil hunting as well in Alberta and the Canadian arctic.

“You just walk and use your eyes. Sometimes, you’re literally on your knees. The closer you are to the ground, the better. Nobody ever looks for fossils on horseback,” he said.

“Fieldwork is a fun part of the job. It’s also very rewarding. It’s hard work. It can be hot and sweaty,” he said.

The prairie provinces of Canada are his favorite places for fieldwork.

“If you go out in the field there, you will find something. You always find something,” he said. “And with that comes new discoveries.”

The mosasaur is a perennial favorite of dinosaur lovers because of their immense size and menacing appearance. Konishi understands why mosasaurs are a pop-culture staple.

While the 2015 film “Jurassic World” spotlighted Konishi’s research subject for a global audience, the moviemakers weren’t sticklers for scientific accuracy, he said.

For starters, mosasaurs had mouths more like Komodo dragons than crocodiles. And the mosasaur featured in the movie’s aquarium was far bigger than any known specimen.

Likewise, the monster portrayed on screen had knobby plates like a crocodile, which would have been a hindrance for truly aquatic reptiles. And — spoiler alert — a mosasaur probably couldn’t have beached itself to grab a genetically engineered dinosaur by the tail.

“Being an expert makes me savvy about that pop-culture aspect of a charismatic prehistoric, toothy predator. And they are,” he said. “So I enjoyed the movie.”

UC graduate student Samuel Garvey is studying the dentition of mosasaurs to learn more about what prey they likely hunted in Cretaceous seas.

Field research to labwork

Do you like field research? At UC, biology students get hands-on experience in their chosen subject area. Check out the Department of Biological Sciences or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.