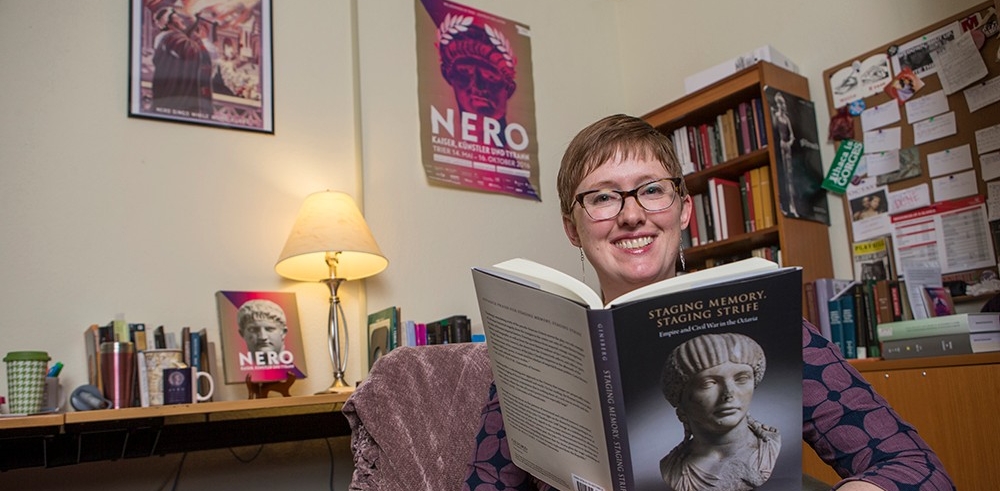

University of Cincinnati classicist Lauren Donovan Ginsberg is the author of the new book "Staging Memory, Staging Strife: Empire and Civil War in the Octavia." Photo/Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

Lifting the curtain on

Rome’s first imperial family

From Augustus to Nero, Romans treated the Julio-Claudian

emperors like gods during their reigns and condemned them

as monsters after their deaths. A new book by a University of

Cincinnati classicist offers the first detailed study of how the only

surviving literary witness to the dynasty’s rise and fall reinterprets

the history of Rome’s first imperial family.

There are two histories of Rome’s first imperial family, the Julio-Claudians, says Lauren Donovan Ginsberg, an assistant professor of classics at the University of Cincinnati.

The dynasty begins in 31 B.C., when Augustus seized absolute power in the wake of Julius Caesar’s death, promising a new age in Roman history in which order and peace would be restored to an empire weary of decades of bloody civil war.

And so, as the story goes, over the next nearly 100 years, the Julio-Claudians — Augustus and his four successors — acted as divinely ordained bringers of peace who built massive monuments, extended Rome’s borders and wealth and ushered in a golden age of Roman literature and arts.

But in the years after the 68 A.D. suicide-death of Nero, the last of the line, another narrative emerged, one that challenged this rose-colored view of the infamous Roman emperor Nero and the Julio-Claudian dynastic legacy that produced him.

“Octavia,” the only surviving historical drama from ancient Rome, portrays the Julio-Claudian regime not as saviors of an imperiled state, but rather as autocrats prone to self-indulgence, Machiavellian backstabbing and tyrannical cruelty.

Reading the larger messages between the play’s 982 lines has been a decade-long undertaking for Ginsberg, who reveals her findings in her new book, “Staging Memory, Staging Strife: Empire and Civil War in the Octavia.”

The book, published by Oxford University Press, examines how the play uses the dramatization of the three-day period in which Nero divorces and exiles his popular wife Octavia — a move that launched riots among Romans loyal to their beloved empress — as a wider lens to expose the dark legacy of Rome’s first imperial family.

“I’m interested in how literature helps shape how people will be remembered, especially more controversial figures. How does this play teach us to approach the memory of Nero and the memory of the dynasty that gave rise to him?” she said.

Reviving ‘Octavia’

Although “Octavia” was written nearly two millennia ago, Ginsberg’s is the first book-length literary study of it. Classicists, wary of its anonymous playwright and unknown date, tend to dismiss it as not “historical” enough, while dramatists often pass it over for works with more theatrical intrigue, she explained.

“Somehow this drama seems, on one hand, boring to dramatists because there’s no murder at the center of it, and to historians, ridiculous because Nero’s mother comes in the middle of the play as an avenging fury that haunts his nightmares,” said Ginsberg. “It doesn’t really satisfy either camp of people.”

Murder might not appear in “Octavia,” but audiences of the time were well aware that each of its cast members would eventually meet untimely and gruesome deaths, she said.

Nero by artist Abraham Janssens van Nuyssen. Photo Credit: Ralf Roletschek/WikiCommons

There’s the ambitious and power-hungry Agrippina the Younger, Nero’s mother, who poisoned her husband and Nero’s adoptive father, Claudius, to ensure her 17-year-old son’s speedy ascension to the throne.

Turnaround was fair play for Nero, however, who later devised a plot to sabotage a boat that would fall apart at sea, making it appear as if Agrippina tragically drowned in a shipwreck. When the death trap failed and Agrippina proved quite the hardy swimmer, he dispatched assassins to kill her.

To seal his claim to power, Nero married Claudius’ daughter, Octavia, a fiercely popular “Princess Diana-like” figure among the Roman people, and bumped off her brother, Brittannicus, to clear away a rival for the throne. When Octavia, understandably none too happy with the murders of her father and brother, rejected Nero, he had her banished, murdered and beheaded.

Next came the order for his longtime tutor and advisor, Seneca, to commit suicide. The bloody housekeeping then continued with the death of Nero’s second wife, a very pregnant Poppaea, whom Nero kicked in a fit of rage.

As if these monstrosities weren’t enough, there’s also the spurious rumor that Nero ignited the fire that destroyed Rome, played music (or “fiddled”) while the city burned and then blamed it on Christians (including saints Peter and Paul) who were rounded up and killed in the most sadistic of ways as he set about building a gilded new palace for himself amidst the city’s ruins.

Rethinking Nero

Sure, Nero has become synonymous with the debaucheries, destruction and disgrace of ancient Rome, says Ginsberg, but even monsters have another side.

The Torches of Nero, by Henryk Siemiradzki. According to Tacitus, Nero targeted Christians as those responsible for the fire. Credit: WikiCommons

The flamboyant young emperor had a passion for music and the theater — a pleasure largely associated with the common people — and staged popular public performances. His new coinage standards endured for a century. And while he was blamed for the horrific blaze that devastated much of Rome, he also organized relief efforts and implemented building fire safety codes.

“The empire was pretty stable under him and the economy did well,” said Ginsberg. “The common people loved Nero, partly because he wasn’t snobby and would do low-class things.”

“He definitely became more and more tyrannical, and by the end, he is closer to the tyrant that we know him as,” she quickly added, “but he was still keeping the ship upright and was probably one of the more popular emperors in terms of common popularity.”

Long after his death, Nero retained what Ginsberg calls a “cult of personality,” inspiring Nero-branded swag especially popular among women, flowers left at his grave and even performances of his poems and speeches.

“There were actual Nero pretenders, people who I would compare to Elvis pretenders who would come back and claim to be Nero,” said Ginsberg with a laugh. “Armies, especially in the East, would flock to them — there would be literal unrest in the empire because they believed that it was their beloved Nero come back to them.”

“My book in no way tries to rehabilitate Nero, but it does try to say in whose interest it was that all of these myths rose up. Nero could have been remembered as a great emperor who died young, but he wasn’t. Who made sure that he would be remembered this way?”

‒ Lauren Donovan Ginsberg

So, why does Nero have such a bad rap? And why is the play “Octavia” so critical of him and the Julio-Claudian dynasty? Understanding the competing political forces driving early Roman literary and cultural memory lies at the heart of Ginsberg’s work.

“My book in no way tries to rehabilitate Nero, but it does try to say in whose interest it was that all of these myths rose up,” said Ginsberg. “Nero could have been remembered as a great emperor who died young, but he wasn’t. Who made sure that he would be remembered this way?”

Exploring the answers to those questions through the lens of stagecraft, she says, seems only fitting for an entertainer-in-chief who was perhaps better suited for the stage than the throne.