The skull and connecting mandibles of a 12,500-year-old flat-headed Peccary (Platyganous compresus) excavated from Sheriden Cave, Ohio. Representing the most recent specimen ever dated and known to have lived, these bones were part of the last gasp of the last ice age. Photo/Peter Bostrom/Lithics Casting Laboratory

Ancient platinum rain likely led to Earth's last big chill

UC anthropologist helps discover rare elements across North America –– critical evidence for cosmic impact dating back to onset of the last ice age.

While scientists still ponder the reasons for the Earth’s last big freeze more than 12,000 years ago, University of Cincinnati anthropologist and geologist Kenneth Tankersley is participating in recent multicollaborative research led by the University of South Carolina that may hold the cold secret for mass extinction.

The discovery of widespread platinum found in soil layers at archaeological sites across North America were found to coincide with a geological period called the Younger Dryas, an era of the Earth’s sudden cooling beginning 12,800 years ago.

“This mysterious frozen epoch, also blamed for the eventual disappearance of the early woolly mammoth, mastodon and saber-toothed tiger lasted for a brief period of about 100 years,” says Tankersley, UC associate professor of anthropology and geology. “But the reasons for this rapid freeze remain unclear and have been cause for ongoing scientific debate for decades.”

Tankersley believes the presence of elevated platinum in the soil layers found in several archaeological sites across the country, including his own work at Sheriden Cave in Ohio, confirms the data corresponding with the Younger Dryas onset reported in an earlier Greenland ice-core study. That study recorded a possible source of platinum present in the sediment in Greenland that may be the result of an extraterrestrial cosmic impact, he says.

View from inside Sheriden Cave opening.

Cold shoulder's last gasp

In recent findings summarized in a paper published this month in the prestigious journal Nature/Scientific Reports, the same platinum anomalies were found in the U.S. archaeological sites that date to the same period. The paper, titled “Widespread platinum anomaly documented at the Younger Dryas onset in North American sedimentary sequences,” is lead authored by Christopher Moore, of the University of South Carolina, and 12 researchers including Tankersley and represents the findings from 11 archaeological sites throughout the U.S.

Tankersley refers to the period of Younger Dryas as “the last gasp of the last ice age” and explains its name as deriving from a wildflower, the Dryas octopetala, found abundant in the late glacial period. He says this era is also consistent with the extinction of more than 35 species of ice age animals and a change in hunting and gathering by the early Clovis humans.

“Our results show that platinum occurs in ice age sediments in the U.S.,” says Tankersley. “This rare element can be found in periods that characterize atmospheric fallout from a cosmic impact.”

Christopher Moore, the study’s lead author and professor of archaeology at the University of South Carolina, had stated that the rare platinum found in the 11 U.S. archaeological sites from this study is very similar to the iridium found in rock layers dated 65 million years ago from the cosmic impact that caused dinosaur extinction –– an event commonly known as Cretaceous-Tertiary or K-Pg by scientists.

"In both cases, the anomalies represent the atmospheric fallout of rare elements resulting from an extraterrestrial impact," Moore says.

Researchers navigate the dark, narrow tunnels in Sheridan Cave.

Tiny elements, big impact

The researchers say the K-Pg dinosaur extinction was the result of a very large asteroid impact while the Younger Dryas onset is likely the result of being hit by fragments of a much smaller comet or asteroid, possibly measuring up to two-thirds of a mile in diameter.

The study notes another difference –– the Younger Dryas impact event has not been associated with a known impact crater. Instead, the researchers theorize that the fragments of a larger object struck a glacial ice sheet or may have exploded earlier while in the atmosphere, raining platinum and rare elements among the debris creating a chain of devastation.

With the help of UC anthropology graduate student, Mary Ann Ballyntine, Tankersley hand excavated sediment samples from a naturally exposed wall profile in the back of Sheriden Cave.

Collecting the samples in a continuous fashion from youngest to oldest strata, or layers of naturally formed material, magnetic analysis was performed to determine whether these strata were deposited in a cool-dry or warm-moist environment.

Back at the lab, Tankersley used various mass spectrometry analysis techniques to determine the age of the platinum content. Lewis Owen, UC professor of geology offered his expertise in dating the older sediments by employing an optical stimulated luminescence technique, which provides a measure of time since sediment grains were deposited and shielded from further light or heat exposure.

As with a supervolcano, Tankersley says the spike in the trace element of platinum is a fingerprint for widespread particulate matter that would have enriched particles in the atmosphere and led to global cooling.

The researchers conclude that the presence of platinum is an easily identifiable hemispheric marker in sediment layers for the start of Younger Dryas. This discovery contributes to the supposition that a potential cosmic impact event occurred, which warrants further scientific investigation.

“Our results show that this rare element platinum occurring in ice age sediments in the U.S. can be found in periods that characterize atmospheric fallout from a cosmic impact.”

‒ Kenneth Barnett Tankersley

Ancient remains inside Sheriden Cave, Ohio, of extinct forms of the flat-headed peccary residing amid samples of platinum dating 12,500 years ago.

Tankersley’s work in Sheriden Cave in northern Ohio includes collaborative teamwork with representatives from other archaeological sites such as Arlington Canyon on Santa Rosa Island, California; Murray Springs, Arizona; Blackwater Draw, New Mexico; Squires Ridge and Barber Creek, North Carolina; and Kolb, Flamingo Bay, John Bay and Pen Point, South Carolina.

Researchers involved in the study include:

Christopher R. Moore and Mark J. Brooks, Savannah River Archaeological Research Program, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina; Allen West, GeoScience Consulting, Dewey, Arizona; Malcolm A. LeCompte, Center of Excellence in Remote Sensing Education and Research, Elizabeth City State University; I. Randolph Daniel, Jr., Department of Anthropology, East Carolina University; Albert C. Goodyear, South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology; Terry A. Ferguson, Department of Environmental Studies, Wofford College; Andrew H. Ivester, Department of Geosciences, University of West Georgia; James K. Feathers, University of Washington, Luminescence Dating Laboratory; James P. Kennett, Department of Earth Sciences and Marine Science Institute, University of California, Santa Barbara; Kenneth B. Tankersley, Departments of Anthropology and Geology, University of Cincinnati; A. Victor Adedeji, Department of Natural Sciences, Elizabeth City State University and Ted E. Bunch, Geology Program, Northern Arizona University.

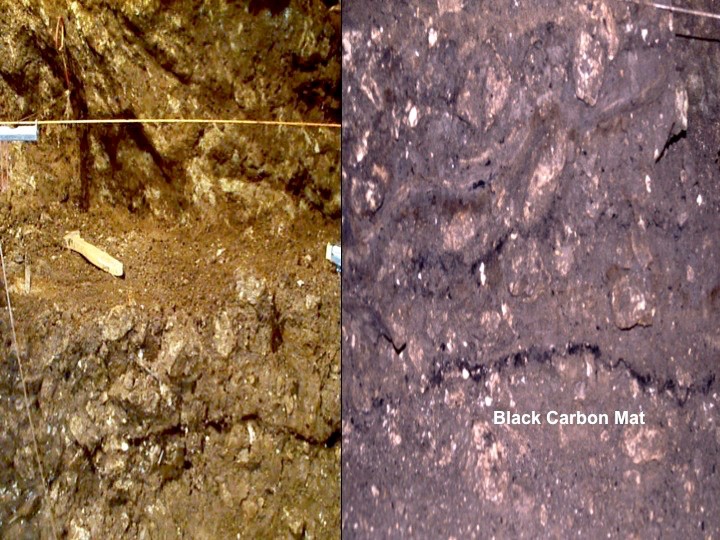

Professor Tankersley (blue hat) with graduate student Mary Ann Ballyntine (yellow hat) inspect the black mat carbon layer inside Sheriden Cave. On right, a close-up of the ancient black mat carbon layer with platinum found inside Sheriden Cave dating precisely to the end of the last ice age and mass extinction event.

The University of Cincinnati Department of Anthropology is committed to both scientific and interpretive approaches to the study of human diversity. Faculty and students in the department conduct empirical research, using both quantitative and qualitative methods and analytical techniques. The faculty specialize in three traditional subdisciplines: archaeology, biological anthropology and cultural anthropology. Many of the researchers, however, work on topics that transcend traditional subdisciplinary boundaries and also collaborate with scholars from other disciplines. As such, the faculty focus their research and teaching around three key themes:

- Bioevolutionary Approaches to Health

- Ecosystem Dynamics

- Forms of Social Inequality

The department is also global in orientation, with active field research from Madagascar to Mongolia and the forests of Nicaragua to fashion week in New York City. Please visit the webpage.

UC’s Department of Geology is a nationally ranked program with high-caliber faculty and a strong research reputation. The faculty strive to provide undergraduate and graduate students with the knowledge and expertise necessary to be prepared for future endeavors in academia and employment. The program offers both Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science degrees at the undergraduate level and Master of Science doctoral degrees at the graduate level. The department also offers a 4+1 program in which current BS or BA students can earn a non-thesis master’s degree with an additional year of study and research.