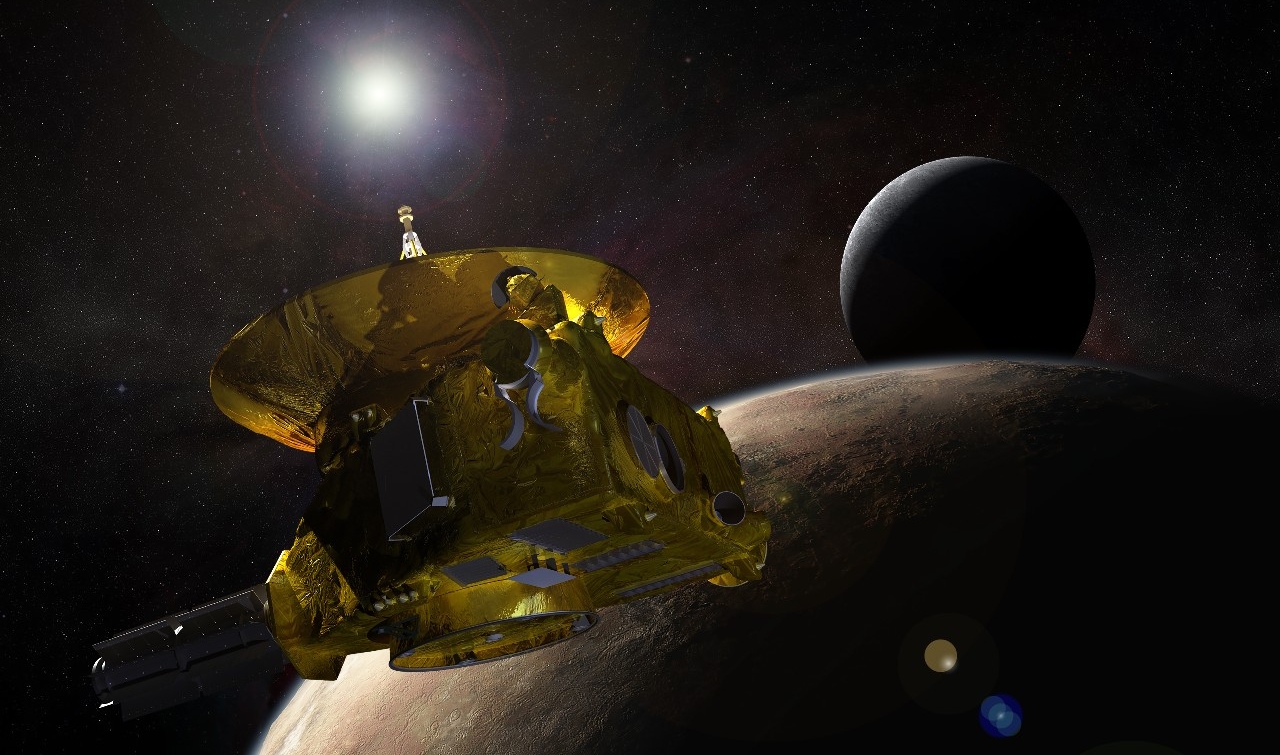

An artist’s rendering of New Horizons as it appeared in front of Pluto. The project leader, Alan Stern, will speak at UC on Sept. 8. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

To Pluto and beyond

The principal investigator of NASA’s New Horizons mission is coming to UC to talk about the spacecraft’s close encounter with Pluto and its next target 4 billion miles from Earth.

NASA’s successful mission to Pluto in 2015 was spurred by a graduate student with a big idea.

Alan Stern was finishing his astrophysics degree at the University of Colorado Boulder in 1989 when he approached NASA with the notion of sending a spacecraft to Pluto.

Pluto is the farthest planet (some prefer dwarf planet) from the sun in our solar system. After NASA’s Voyager 2 probe sent back the first detailed images of Neptune from space in 1989, Pluto was an obvious target of scientific conquest. But it took more than 15 years of prodding and perseverance by Stern and other supporters to get a mission off the ground.

Today, the New Horizons spacecraft is hurtling hundreds of millions of miles past Pluto through the Kuiper Belt, a distant ring of rock and ice, where the probe will rendezvous with an asteroid-like object the size of Greater Cincinnati some 4 billion miles from Earth.

Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons and NASA’s former chief science officer, will visit UC to talk about the mission at 3 p.m., Sept. 8, at Tangeman University Center’s Great Hall.

Stern is a planetary scientist and vice president of space science and engineering at the Southwest Research Institute, a nonprofit that works with government and industry.

“When I look back, I think of all the many people who made New Horizons happen,” Stern said. “Their persistence over many difficulties and setbacks produced a breakthrough project that inspired a lot of people and shattered the mold for low-cost planetary exploration.”

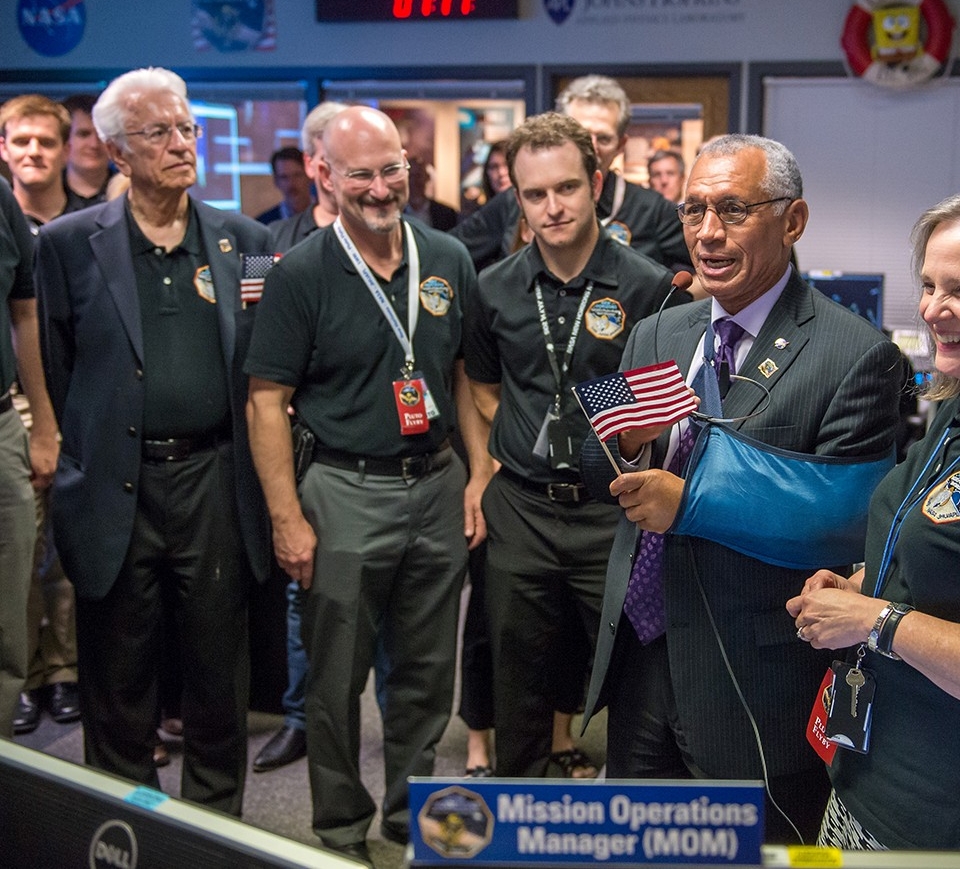

Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons, talks about the 3-billion-mile mission to Pluto. (NASA/Joel Kowsky)

If you go:

NASA’s former chief science officer Alan Stern will talk about the New Horizons project at 3 p.m., Friday, Sept. 8, at UC’s Tangeman University Center Great Hall. Admission is free.

About Pluto:

• Discovered in 1930 by astronomer Clyde Tombaugh.

• Has five moons, including Charon, who in Greek mythology ferries the souls of the recently deceased over the river Styx to the land of the dead.

• Diameter of 1,475 miles, smaller than our moon.

• Ranges from 2.7 billion to 4.7 billion miles from Earth, depending on planetary orbits.

Source: NASA

Years of planning

UC physics professor Margaret Hanson was a classmate of Stern’s at the University of Colorado. She invited him to speak at UC. Besides the obvious interest in the project among astrophysicists, UC geologists, geographers and engineers are following the mission closely, too, she said.

“The tenacity of Alan to get this done is just incredible. It was canceled so many times, redesigned so many times. This would not have happened with anyone else,” she said.

The project endured multiple series of congressional approvals and funding cutbacks that threatened to derail it. Stern said thousands of people played a role in planning the project, building the spacecraft and its systems and executing the mission.

“It was thanks to a lot of people – and trust me, I get too much credit for this. It’s not my project. It’s our project,” he said.

A technician wraps the half-ton New Horizons spacecraft in a protective heat shield at the Kennedy Space Center. (NASA)

And then calamity

The spacecraft launched in 2006 and traveled uneventfully toward Pluto for more than nine years. But on Independence Day of 2015, just 10 days before New Horizons was to reach its target, the spacecraft went dark.

Stern’s team had lost communications.

“It was heart-wrenching. It was flying across the solar system for almost nine-and-a-half years, and it never had a moment like that,” Stern said.

Over the long holiday weekend, the team scrambled to diagnose the problem and figure out a solution with the prospect of failure looming as big as the approaching planet. Everyone understood the implications, but nobody panicked, Stern said.

“You really don’t have a choice. You can panic and go bounce off the walls. But after a half-hour, what are you going to do? You’re back in the same place anyway,” he said. “We’re here. This happened. Let’s buckle down and solve the problem.”

UC graduate Chris Hersman (red badge, center) celebrates the successful rendezvous of New Horizons with Pluto in 2015. (NASA)

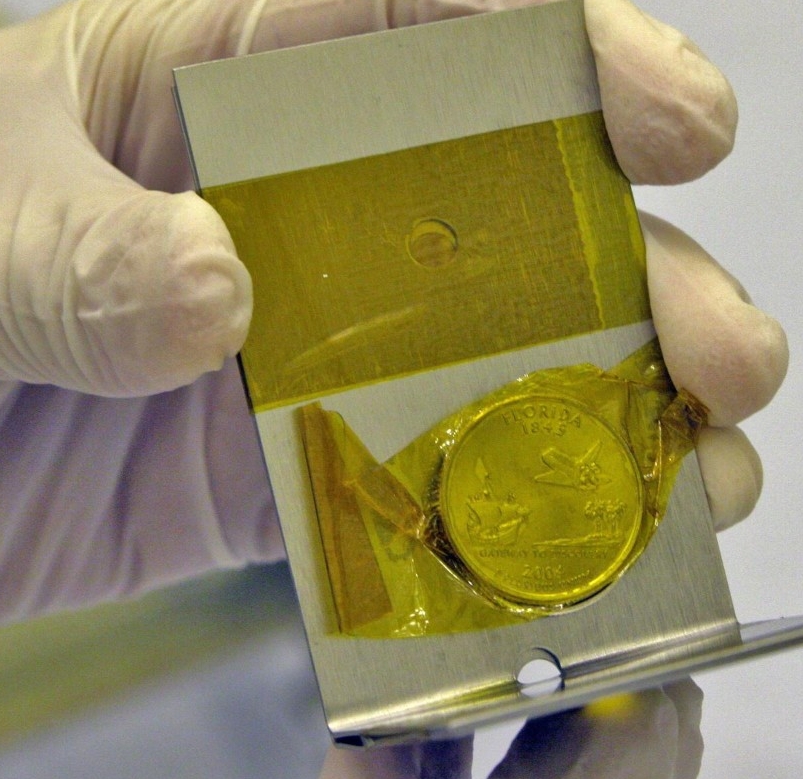

New Horizons is carrying a Florida quarter engraved with a “Gateway to Discovery” design. Also onboard is a Pluto postage stamp from the U.S. Postal Service’s planets series. The 1991 stamp reads “Not Yet Explored.” (NASA)

'48 hours of terror'

Engineers and staff worked around the clock for days, sleeping under their desks while they puzzled over the problem. Among them was UC graduate Chris Hersman, a 1988 alum of the College of Engineering and Applied Science, who served as New Horizons’ mission systems engineer. In a 2015 UC Magazine interview, he described the crisis as “48 hours of terror.”

“These were very complex activities that under normal circumstances might have taken months to coordinate, practice and execute – all in the space of just three days,” Stern said.

The team determined that New Horizons’ computers were overloaded after it received Pluto flyby instructions while compressing data. The multiple operations caused a software conflict that prompted the computers to go into safe mode.

“Chris is one of the smartest people I’ve ever met,” Stern said. “He has the entire design of the spacecraft and how it operates in his head. There have been countless occasions where Chris’ contributions made the difference between success and failure.

“If it weren’t for Chris Hersman, there would have been no exploration of Pluto.”

UC graduate Chris Hersman, mission systems engineer for New Horizons. (NASA)

“If it weren’t for Chris Hersman, there would have been no exploration of Pluto.”

‒ Alan Stern, principal investigator for New Horizons

Mission success

Meticulously, the team dispatched instructions to the spacecraft nearly 3 billion miles away. Each transmission took more than four hours to reach New Horizons as the spacecraft streaked toward Pluto at 32,500 miles per hour.

“We crammed months of work into those three days, with no possibility of a second chance, and got it right,” Stern said.

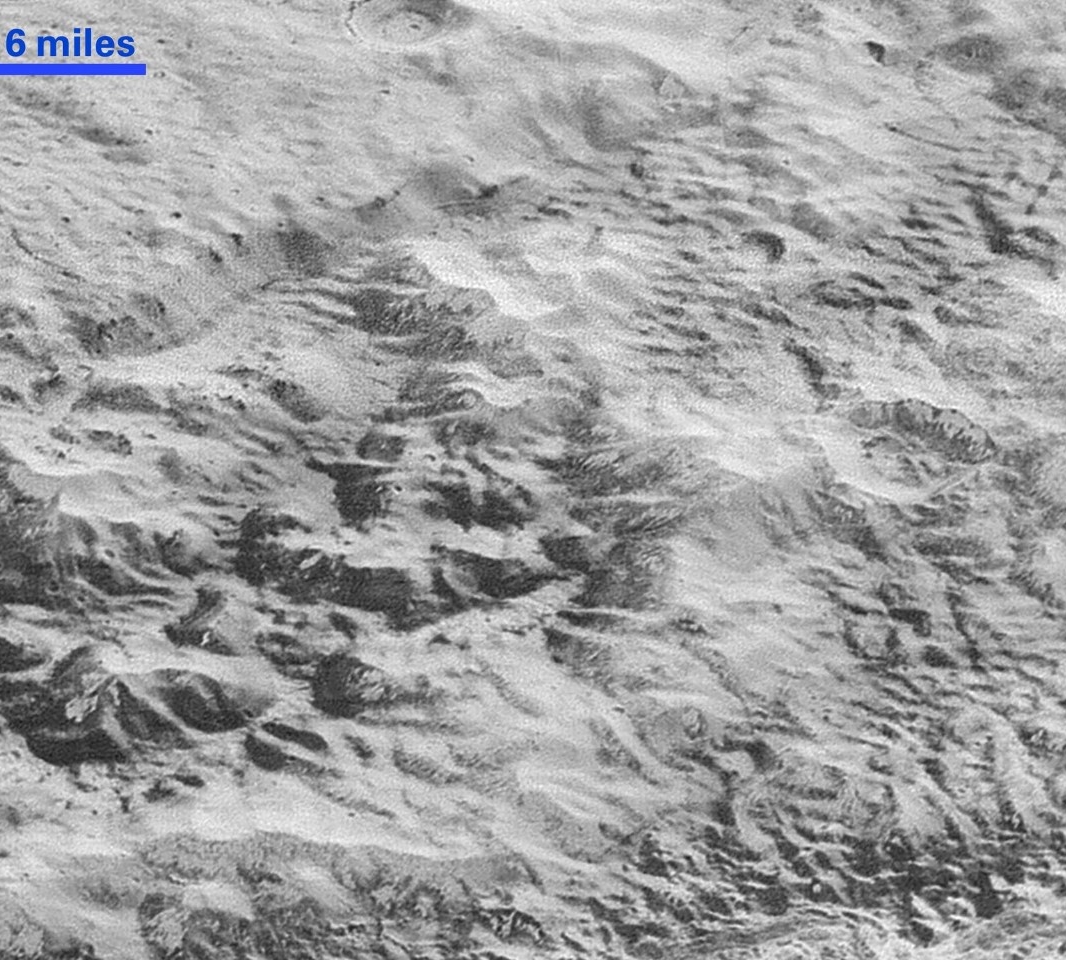

Communications with New Horizons sprung back to life on July 7 as if nothing had happened. Days later, the spacecraft successfully skirted past Pluto and its moons, sending back extraordinary and intimate images of Pluto’s ice-capped mountains the size of Grand Teton.

New Horizons was able to:

• Capture high-resolution photos of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon.

• Record a miles-deep canyon on Charon.

• Observe Pluto’s four other moons.

• Learn more about Pluto’s thin atmosphere.

New Horizons captured this image of what scientists call Pluto’s “badlands,” an area of rugged hills fronting a 1-mile-tall cliff. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

Observations continue

Now, New Horizons is flying more than 1 billion miles beyond Pluto in the Kuiper Belt, where it is shedding light on the origins of the universe 4.5 billion years ago. The spacecraft will intercept an asteroid-like object called MU69 in 2019. Stern said his team hopes to learn about its origins, geology and atmosphere.

“It’s a billion miles farther out than Pluto. It’s on the very frontier of human knowledge,” Stern said. “So we can learn about the very origins of our solar system.”

New Horizons will explore the Kuiper Belt through 2021. After that, the spacecraft will continue its deep-space exploration, sending back data and images as one of Earth’s most distant observatories.

“The spacecraft is in almost perfect health. There is really nothing wrong with it. We’re not using any of our backup systems. And all of our backup systems are healthy,” he said. “So there’s a long and bright future for New Horizons into 2030.”

Next frontier

UC’s Hanson said the scientific achievement that New Horizons represents can’t be overstated. The mission was fraught with urgency to take advantage of the gravitational assists of other planets and reach Pluto during its comparatively short summer before its atmosphere froze and settled back onto the surface on its long winter trip around the sun.

And just like the fictional kingdom of Westeros featured in HBO’s “Game of Thrones,” Pluto’s seasons take human generations during its elliptical 248-year orbit of the sun. The next chance scientists will have to observe Pluto’s atmosphere will be about two centuries from now. Pluto will be closest to the sun again in 2237.

“They couldn’t wait. There definitely was a time crunch there,” Hanson said.

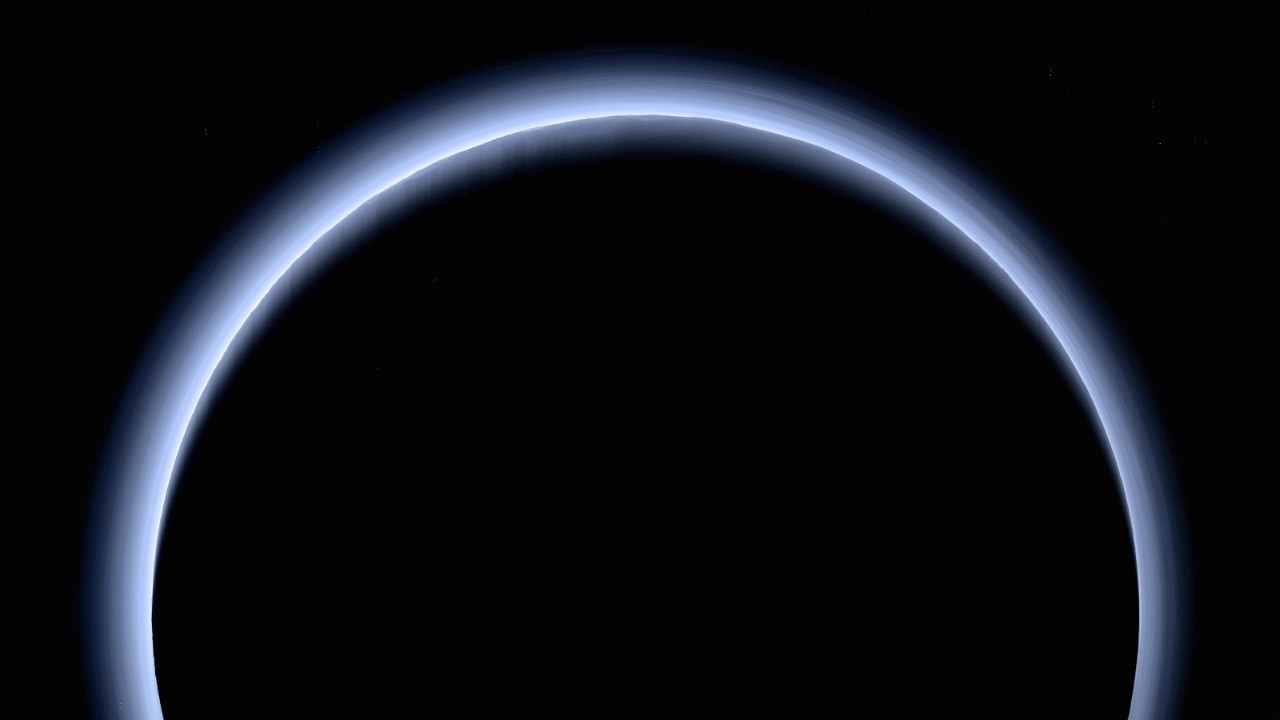

By launching when it did, New Horizons was able to capture stunning images of Pluto’s ice-blue atmosphere. Hanson credited the dedication of Stern and his team for the mission’s success.

“He’s super-enthusiastic and he always has been. You have to have that passion and determination and willingness to take risks,” she said.

And it all started with a graduate student with the courage to ask why not?

“My dream was to explore the farthest planet ever explored,” Stern said. “Follow your dreams. Follow your heart. Stick with it. Do the things that you love and you can accomplish amazing things. That’s the lesson.”

New Horizons captured the blue haze of Pluto's methane atmosphere during the spacecraft's 2015 flyby. (NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Southwest Research Institute)

UC grads explore the universe

Students in UC's physics programs are helping to shape our understanding of the universe. Check out the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences or other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.