UC graduate and Predictronics CEO Edzel Lapira talks about the $4.5 billion predictive analytics industry.

Say goodbye to guesswork

UC graduates founded a predictive analytics company that gives manufacturing clients more certainty in an uncertain world.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services

Sept. 22, 2017

Machines have been talking to us for years.

Now, thanks to advances in technology, we’re starting to listen, said Jay Lee, director of the University of Cincinnati’s Center for Intelligent Maintenance Systems.

Lee, an Ohio Eminent Scholar, teaches predictive analytics, a science that combines mechanical engineering with statistics and math to determine when complicated machines or systems might fail.

In 2012, Lee inspired some of his students to start a predictive analysis company, Predictronics Corp. Today, the Blue Ash company has 18 employees, mostly engineers and data scientists who help clients save time and money by helping to anticipate when robots, automated equipment or machine systems are likely to break down.

“When you go to the doctor, the nurse takes blood and they run all kinds of tests to see what’s wrong,” Lee said. “If you look at machines, we don’t do that. I used to think, ‘Why not? Why can’t we diagnose machines in the same way?’ That was the fundamental driver behind it.”

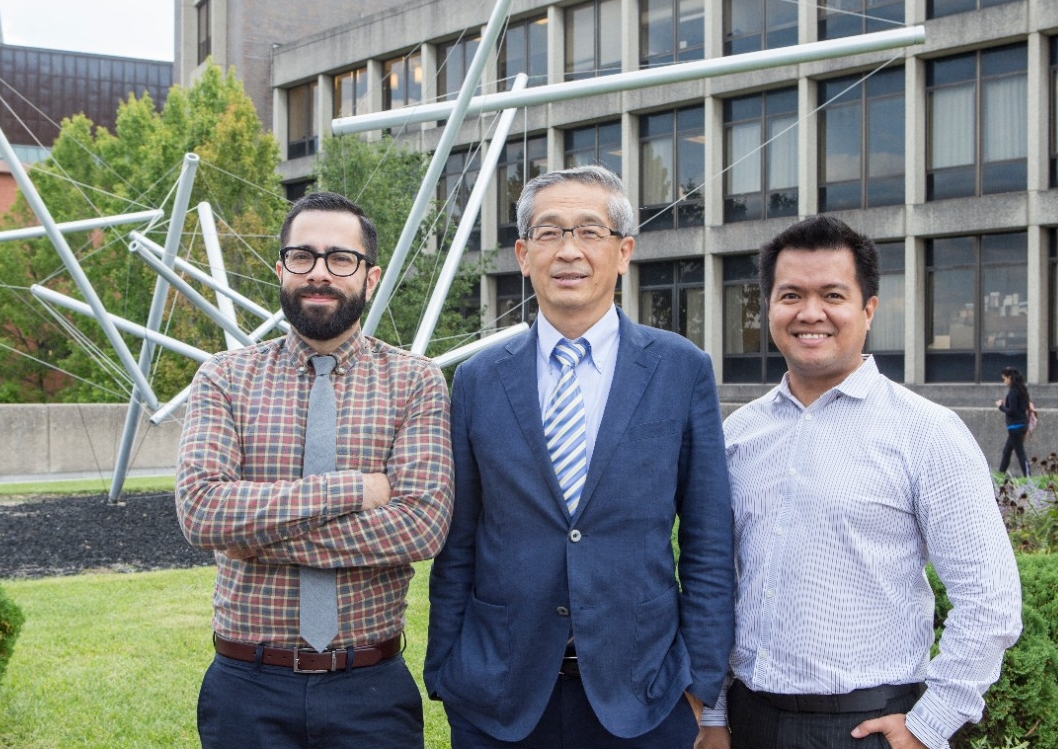

Predictronics was founded in 2012 by UC graduates Edzel Lapira, David Siegel and Patrick Brown.

While machines and medicine have little in common, doctors and engineers have the same ability to use data and past experience to predict when systems will fail, whether it’s a patient’s circulatory system or an automaker’s assembly line.

Predictronics CEO Edzel Lapira, who earned a doctorate at UC, said he co-founded the company at a time when businesses were starting to realize the full potential of predictive science.

Lapira studied audio and video compression for his undergraduate and master’s degrees in the Philippines. But he became intrigued by predictive analysis at UC. He applied this analysis to wind turbines for his dissertation.

“I would not trade the experience I got [at UC] for anything,” he said. “This was definitely what I wanted to do.”

“Everything had to come at the right time. We’re seeing the proliferation of the internet of things. Getting data from machines is getting easier. So the market is right.”

‒ Edzel Lapira, UC graduate and CEO of Predictronics

Predictronics provides consulting services and has a software platform called PDX for collecting and analyzing industrial data. This platform can be applied to a variety of industries. His clients include Nippon Steel and Japanese mining manufacturer Komatsu.

“You don’t need predictive analytics to replace a lightbulb,” Lapira said. “But if the gearbox of a robot fails, replacing it is an expensive pain-in-the-neck. You’d like to do that proactively and during a scheduled shutdown so you don’t affect production.”

The $4.5 billion predictive-analytics industry is expected to see aggressive growth in the next five years.

The $4.5 billion predictive analytics field is expected to see explosive growth globally over the next five years. Market analysts expect this niche to more than double in size by 2022.

“Everything had to come at the right time. We’re seeing the proliferation of the internet

of things. Getting data from machines is getting easier. So the market is right,” Lapira said.

Predictive analysis uses a combination of engineering know-how and big data to determine when machine parts or systems will break down, said David Siegel, Predictronics’ co-founder and chief technology officer.

Shutdowns for repairs are inevitable. But they can be especially costly when they are unexpected.

“If someone said that your robot will fail in a week or two, you would take action ahead of that failure — do it more conveniently so there is no stoppage during production,” Siegel said.

Predictronics CEO Edzel Lapira

"Machines talk through data, but nobody was listening. We had a visionary director at UC, Jay Lee, who said we should listen."

‒ Edzel Lapira, UC graduate and CEO of Predictronics

The industry’s players include some of the biggest technology companies in the world: IBM, Microsoft Corp., Dell Inc. and Oracle Corp., among others. But smaller startups such as Predictronics are creating stiff competition, spurred by the ubiquity of computer sensors that manufacturers are adding to machines.

“It’s partly the technology. But people are realizing the value it provides in improving productivity and saving money,” Siegel said.

This foresight leads to surprising savings, said Patrick Brown, co-founder and chief financial officer for Predictronics and program director at UC’s Center for Intelligent Maintenance Systems. The center, part of UC’s College of Engineering and Applied Science, opened in 2001. It has worked with 115 companies in 15 countries around the world.

UC’s center is part of the National Science Foundation’s Industry-University Cooperative Research Centers program. An independent study in 2012 estimated that UC’s center and four others in the foundation’s program saved participating businesses a combined $827 million, Brown said.

“We were considered among the most impactful of the centers,” he added.

Brown, who is also a UC graduate, said more companies are incorporating data collection in the design of their robots and machines to make it easier for their clients to maintain them once they’re up and running. This creates a feedback loop that will help spur the predictive analytics industry, Brown said.

“They see it as an opportunity to make their machines more reliable and provide additional services to customers,” Brown said. “They’re driving their customers to adopt these technologies and vice versa. It’s interesting to see customers pushing for it and original equipment manufacturers selling it.”

Predictronics works with a variety of manufacturing companies. But predictive analytics has broad applications.

As students, many of Predictronics’ executives and employees took part in UC’s nationally recognized cooperative education program, in which students work at companies in their chosen field for part of the school year. Predictronics is continuing this relationship by offering its own co-op positions to UC students.

UC graduate student Debayan Basu, 27, worked at Predictronics over the summer. He is getting his master’s degree in information systems from UC’s Carl H. Lindner College of Business and hopes to pursue a career in predictive analytics.

“It’s a good learning experience and it’s fun because you can see how the data is being used,” Basu said. “You can help the user find his way through the data.”

Predictronics’ Lapira said he expects his business to grow with the industry. He is excited about working in a field of science designed to bring more certainty to an unpredictable world.

“There is still a lot of work to do,” Lapira said. “But we’ve been fortunate to work with partners and investors who believe in us.”

UC graduate Edzel Lapira, right, worked with UC engineering professor Jay Lee, center, and Patrick Brown, both with UC's Center for Intelligent Maintenance Systems, to launch Predictronics in 2012.

Become a Bearcat

Do you have an entrepreneurial spirit? At UC's College of Engineering and Applied Science, students can turn their ideas into businesses. Apply to CEAS or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.