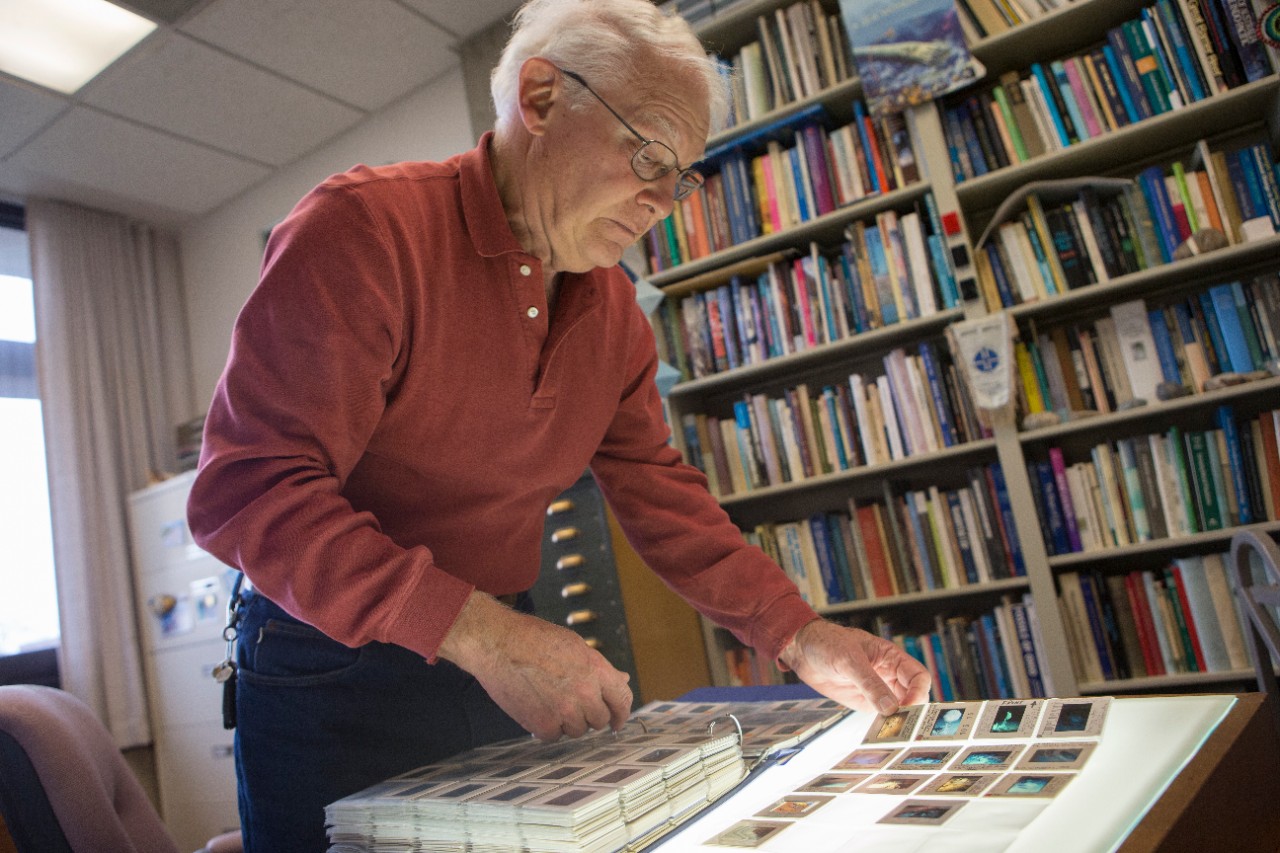

UC professor emeritus David Meyer uses a lightbox to examine slides of photos he shot off reefs around the world. photo/Andrew Higley

Diving deep for data

UC professor emeritus David Meyer is sharing 50 years of underwater photography in a new digital archive.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Andrew Higley/UC Creative Services and David Meyer

Nov. 17, 2017

Paleobiologist David Meyer took his first underwater photograph in 1967, the year he got into diving.

“The first underwater camera I had was a Nikonos 1,” said Meyer, a professor emeritus at the University of Cincinnati. “It was an amphibious camera. You could take pictures above and below the water. It was a real breakthrough.”

Fifty years later, Meyer has accumulated a library of images documenting marine species around the world to understand the ancient ones from the Ordovician Period 450 million years ago that he studied as a geologist in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences.

Now Meyer is sharing his life’s work with the public in UC’s digital repository for scholarly works, Scholar@UC. He is converting his old photographic slides to digital images for UC’s new Global Marine Biodiversity Archive.

“It’s a great retirement project,” he said.

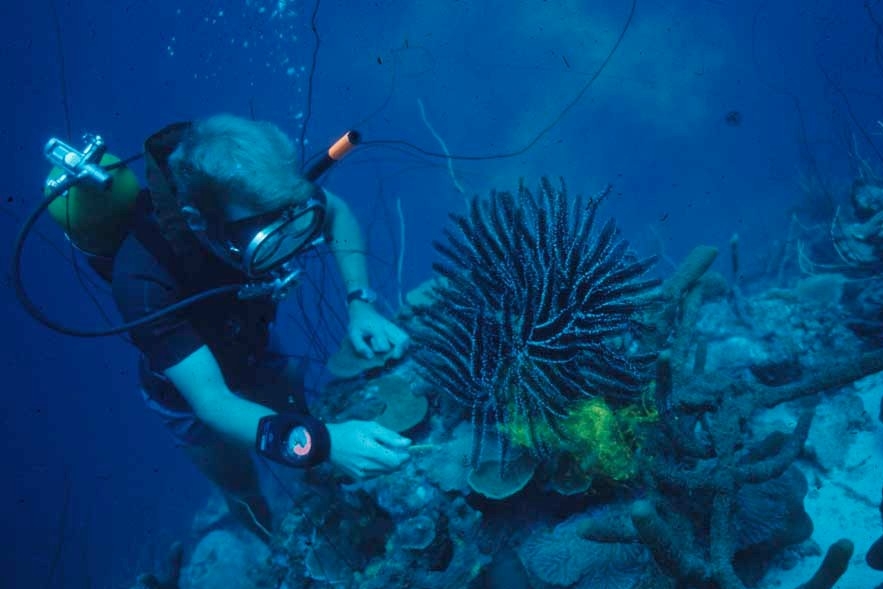

UC professor emeritus David Meyer photographed his dive partner, Sean Jackson, exploring a reef covered in staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis) off Jamaica. photo/David Meyer

A feather star (Phanogenia gracilis) off Palau. photo/David Meyer

Meyer was instrumental in developing UC’s graduate paleontology program. He specialized in crinoids, sea lilies and feather stars associated with tropical reefs. These colorful and symmetrical animals are in the same phylum as starfish and sea urchins. Some have appendages that resemble ferns. Others have stalks like the trees in a Dr. Seuss book.

Rocks dating back to the Ordovician are saturated with these ancient animals. His work includes the 2009 book, “A Sea Without Fish,” which chronicles the ancient ocean life of what is now Cincinnati.

“Photographs were a major part of the data. You’re working with the living specimens. These were key to my understanding the fossils,” Meyer said. “I’m primarily interested in the fossil history of these animals and their evolution from the fossil record.”

Despite working in a landlocked university in the Midwest, Meyer had a chance to study reefs around the world, including the Caribbean, South America and Australia. He even explored the ocean depths in a research submarine, snapping photos through a porthole of creatures illuminated only by the sub’s lights 1,000 feet below the surface.

“You have to be really careful while diving. Safety is a No. 1 concern,” Meyer said. “Your equipment has to be in good condition. You always have to be aware of your surroundings. Is the tide going to change? Will a storm come? And you have potentially dangerous marine life like sharks, but that’s never been a huge problem.”

“We’re hearing about the loss of coral reefs all over the world because of natural and human impacts. Sites that were really pristine are no longer that way at all. It’s another reason why creating this archive is important.”

‒ David Meyer, UC professor emeritus of geology

Fish school around a feather star (Oxycomanthus bennetti) in 20 feet of water off Palau. (David Meyer)

Some reefs he explored 40 years ago have been destroyed by human activity, another reason photo documentation is valuable.

“We’re hearing about the loss of coral reefs all over the world because of natural and human impacts. Sites that were really pristine are no longer that way at all. Jamaica is one example. It’s just totally shocking,” he said. “It’s another reason why creating this archive is important.”

Meyer discovered a new species of feather star. In his image gallery is another Pacific species that also could be new to science, he said.

“We think it’s new because it had a different behavior than a similar one that’s been identified. It comes out at night,” he said.

Meyer’s reef photos have appeared in the Journal of Natural History and American Scientist. His scholarly work has appeared in diverse journals such as Science, the Bulletin of Marine Science and Paleobiology. But he believes researchers should share their raw data when they can, even if it’s not tied to published work.

“A short amount of fieldwork atop a mountain or at a dive site can generate huge amounts of material that will last you years in the lab or at the desk under a microscope,” he said. “We collect all this stuff. But the question is how does all that information get processed?”

That’s why Meyer decided not to restrict access to his collection of photos that he is offering to the public. His photos might help researchers answer questions about marine species he documented more than four decades ago, he said.

“The amount of information collected on geology, fossils and living organisms is huge. But how do people get access to it?” he said. “Accessibility to unpublished information is a big challenge.”

David Meyer

“Photographs were a major part of the data. You’re working with the living specimens. These were key to my understanding the fossils.”

‒ David Meyer, UC professor emeritus of geology

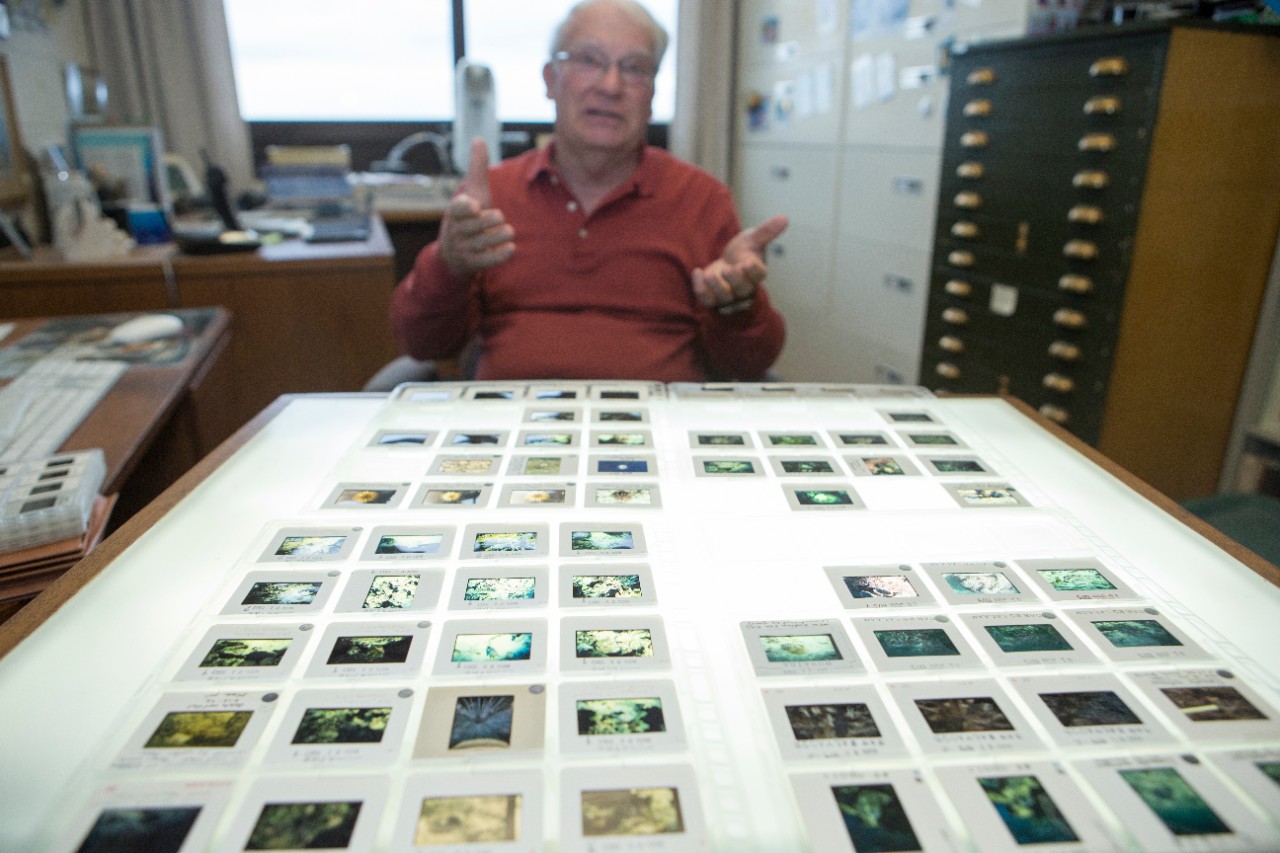

Meyer stored his photo slides in protective plastic sleeves he kept in cabinets out of the sun. But even this medium is ephemeral.

“Slides won’t last forever. They get faded or discolored. They succumb to mold,” he said.

For each photo, he kept meticulous records such as the species depicted, the location, date and depth of the water, among other observations.

Meyer was eager to find a way to preserve his images for generations to come. UC provided a digital solution with its digital archive, which is a key part of UC’s strategy to preserve scholarly work.

Scholar@UC catalogs intellectual work of all kinds, including research papers, raw data and conference presentations. Faculty and researchers can sign in with their UC credentials and upload research to preserve their work and share it with a global audience.

UC professor emeritus David Meyer leafs through his collection of underwater photography he preserved in slides at his office in the Geology-Physics Building. photo/Andrew Higley

UC Associate Librarian Eira Tansey works as the university’s digital archivist, helping to sort records of all kinds for long-term preservation.

“Preservation is not something you can just set and forget,” she said. “It’s a very active process.”

Long-term preservation requires content, infrastructure and people to manage it, she said. Technology offers a solution but also creates complications. Archivists must contend with antiquated hardware and computer programs dating back decades.

“It’s a paradox. It’s easier than ever to create information, which makes it harder to decide what we should save,” she said.

Archivists sort and appraise everything to determine what could be valuable to future researchers. Tansey said over time, records can yield surprising new uses beyond their original purpose. The value of some records might not be known for years.

For example, archivists digitized and shared diaries from the 19th century with the idea that they might be of interest to historians some day. Instead, it was climate scientists who pored over the diaries to gain valuable insights into precipitation records that weren’t available anywhere else, she said.

“By making these records available online, they can reach new audiences,” Tansey said.

UC professor emeritus David Meyer squirts dye into the water to see a crinoid called Nemaster grandis filter-feed in the waters off Curacao. photo/Carl Roessler

Anneissia Bennetti found off Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. photo/David Meyer

Meyer said he hopes his images will be useful for future generations of geologists and marine scientists.

“Let’s hope so,” he said. “Once my photos are in the Scholar@UC archive, they’re accessible across the internet. You just have to Google them.”

Meyer continues to pursue his research interests in his retirement. He took part last year in a 10-day trip to Cuba with a nonprofit conservation group.

“We went down there to do some surveys on the reefs. We did some nice diving and had a good time. We took lots of pictures,” he said. “The reefs there are still very good. In all my years working in the Caribbean, I had never been to Cuba. I wanted to see what was there.”

While he hasn’t done any diving this year, Meyer said he has plenty of destinations in mind.

“There are always more field projects,” he said. “Diving is still something I very much like to do.”

About Scholar@UC

Scholar@UC is an archive of intellectual work of all kinds, including research papers, raw data and conference presentations. Faculty and researchers can sign in with their UC credentials and upload their research to preserve their work and share it with a global audience. The repository also accepts student capstone and senior-design projects, theses and dissertations as submitted by the Graduate School.

Launched in 2015, Scholar@UC completed a major upgrade to its user interface and back-end support. Scholar@UC is an open-source software-development project, with a team of developers in UC Libraries led by Linda Newman, supported by IT@UC and the UC Office of Research. The software code is based on the Samvera framework, an international open-source project. (Samvera is the Icelandic word for “togetherness.”)

Contact the team at Scholar@UC.edu with any questions.

UC professor emeritus David Meyer is digitizing his collection of underwater photography to share with researchers and the public at Scholar@UC. photo/Andrew Higley

Field research to labwork

Do you like field research? At UC, geology students get hands-on experience in their chosen subject area. Check out the Department of Geology or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.