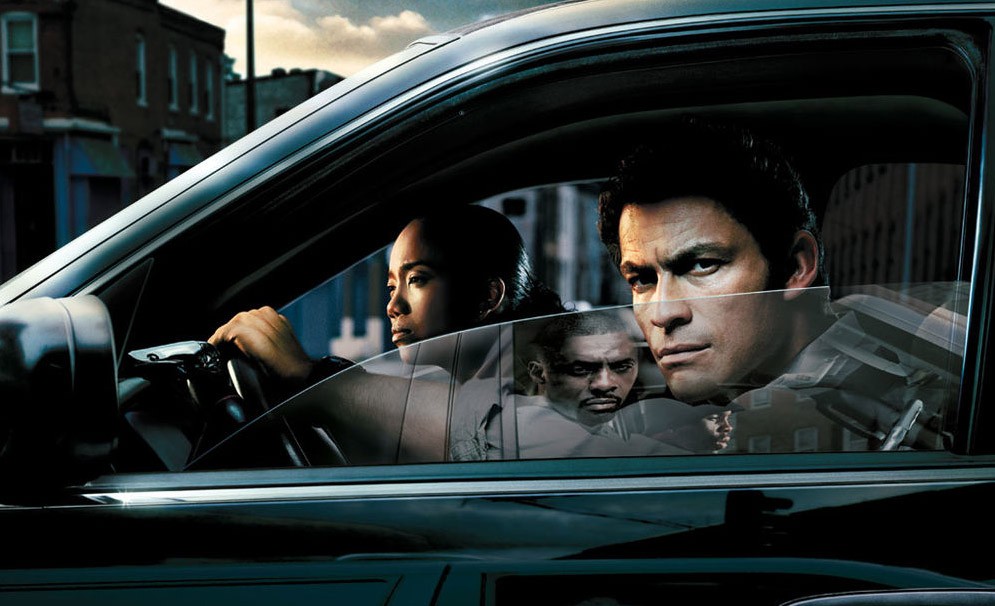

"The Wire" aired on HBO from 2002-08, but still maintains a growing audience today. Photo/HBO

Connecting 'The Wire'

Stanley Corkin's latest book examines HBO's gritty crime drama

by Jac Kern

513-556-1823

Feb. 13, 2017

As University of Cincinnati English and History professor Stanley Corkin enters his 30th year at UC, he adds a new book to his repertoire of works on mass culture (film, television and other popular media) and history.

In this latest release, “Connecting The Wire: Race, Space, and Postindustrial Baltimore,” Corkin offers a season-by-season analysis of HBO’s 2002-08 crime drama “The Wire.”

Following law enforcement in Baltimore, each season explored the police in relation to a different institutional entity: initially, the illegal drug trade, then unionized work on the Baltimore waterfront, city government, the public school system and finally in its last season, the news media.

The show was hailed by critics and adored by fans, but never brought in top ratings or managed to score an Emmy Award. Today, it is universally considered one of the best American television dramas and continues to gain a growing fan base following its run on TV through streaming services like HBO Go and Amazon Prime. Corkin’s book is the first comprehensive scholarly study of “The Wire.”

A key figure in the emerging film program in UC’s College of Arts and Sciences, Corkin’s books include “Realism and the Birth of the Modern United States: Cinema, Literature, and Culture” (1996), “Cowboys as Cold Warriors: The Western and U.S. History” (2004) and “Starring New York: Filming the Grime and Glamour of the Long 1970s” (2011).

“Connecting The Wire: Race, Space, and Postindustrial Baltimore” debuts Feb. 14.

Give us an overview of the book and why you wanted to write about “The Wire.”

I had always endlessly been interested in urban geography. As I was finishing my last book — I’m always trying to think of the next project — one of my kids had brought “The Wire” to my attention. I binge-watched it, and I loved it. I thought it was a great show — sociologically and historically interesting. I’ve written about race and urban life a lot over the course of my career so I thought this would be a natural next thing to do.

The showrunner, David Simon, tried initially to respond to genre expectations in the first season. It’s really within “noir-ish” crime drama caper stuff, but after that, in subsequent seasons, he gives you four different ways of looking at a given American city — in this case, Baltimore — within the context of a neoliberal cultural moment. I thought that was really powerful.

Author and UC professor Stanley Corkin. Photo/provided

“The Wire” is very specific to Baltimore, as opposed to other shows set in New York or Los Angeles or a fictional city. What is the significance of this setting?

Baltimore is below the level of the mega successful, international cities. So the fact that it’s not New York or Chicago or LA; nor is it even San Francisco, Boston, or Houston — which makes it like many cities in a lot of ways. Baltimore is a perfect neoliberal specimen. It’s a city that didn’t quite boom when the economic system changed in the '90s. Cities that didn’t boom, like Cincinnati, kind of got left behind and they’re just of picking up the residue of that restructuring of international economics. And just like Cincinnati now is relatively booming, so is Baltimore.

Who was your favorite character? (Spoiler Alert)

I thought that Stringer Bell was a fascinating character. Simon allowed him to change in dramatic ways and in ways I’ve actually seen people change, over the course of his dramatic trajectory. He is one of those people who life hasn’t really dealt a lot of advantages, but they’re smart and have kind of an unformed body of interests. Bell was allowed to blossom from a student of economics at a community college to an intellectual who is delving into real estate and restructuring the drug trade in order to rationalize it.

When they go into his apartment after he’s murdered, they find books on political theory, economics and even some literary works. McNulty picks up a copy of Adam Smith’s "The Wealth of Nations."

Idris Elba plays Stringer Bell in "The Wire." Photo/HBO

Do you think “The Wire,” a work of fiction, depicts the realities of urban life and crime and policing better than maybe reality shows or docuseries like “Cops”?

In ways it can be truer than those shows. It’s generically fiction. The narrative allows for a greater range of interpretation — I actually talk about this in the book — and if you have an honest and astute interpreter, it allows you to see more of what’s going in the world depicted than a more restricted point of view like in one of those reality TV shows or docu-dramas might show you.

“The Wire” never won an Emmy, even though it was popular among viewers and critics. Why do you think it never struck a chord with the awards circuit?

I think to some degree the gritty, urban textures made difficult for certain Emmy voters to watch. And it had low ratings. In a way, the show has been much more popular after it stopped being on television. More people have watched it on HBO Go and on DVDs. It’s something that took a long time to build up word-of-mouth momentum. The show’s been off TV for nine years, but that doesn’t really matter in relation to my reading audience so much because it retains interest for a large group.

It’s so accessible to watch past shows on Netflix and other services.

And people binge-watch them. For some people, that’s the way they like to watch. Each season has its own compelling, dramatic narrative, so you get hooked, and then season by season.…

The Baltimore waterfront as depicted in "The Wire." Photo/HBO

Who is your audience for this book?

To some degree, it’s an academic audience. Somebody who’s really interested in the topic and the show might pick this up. I think that [University of Texas Press] sees this as something they can market fairly widely. It’s certainly not a statistical sociological study with a lot of charts and graphs. It’s an engaging narrative that picks up on a show that is well known within the broad domain of popular culture.

A very well-known sociologist at Harvard, William Julius Wilson, was one of the inspirations for David Simon. And then I used Wilson as a means of understanding the show, so it's kind of a full-circle thing.

With each of your books, it seems like you focus in more on a particular location, from the West to New York to Baltimore, and concentrating on just one show instead of several films. Did you approach this project differently?

This was the first time I’d written about TV, but writing about TV is not so different from writing about movies because the production values and processes begin to overlap. The focus on just one show was really just happenstance. In ways it’s one show and one place, but in other ways it’s a variety of shows because the writing is different and the direction is different from show to show and season to season.

Dealing with the expanse of “The Wire” over five seasons is really not that different than dealing with a range of movies over, say, a 10-year period. It has the cohesion of a TV series but the TV series in this case is a pretty sprawling thing.

Michael Kenneth Williams portrays Omar Little on "The Wire." Photo/HBO

Have you always been interested in the intersection of pop culture and history?

Yes. I began doing this a really long time ago. When I came to UC there really wasn’t much of a film program, and I would teach a smattering of free-standing courses. I was hired mostly to teach American lit. I chose film a long time ago because I thought — and still think — it was the most important mass culture medium, certainly of the first two-thirds of the century, probably being eclipsed by TV at that point.

But yeah, I’ve always been interested in how mass culture addresses the historical and becomes the historical. I’m teaching a class right now on film and the Vietnam War, and one of the things I’ve been talking to my students about is that the way most people know history is through mass culture. They don’t read history books. What gets repeated frequently in mass cultural objects — it becomes history.

You mentioned that you started to think about this project as you were wrapping up another. Have you thought about what you want to do next?

I have this big project about Boston as a media presence in the post-industrial world. Boston is where I grew up, and it’s a very dramatically different city from the one I grew up in. I go back there a lot. I’ve been writing about kind of the imprint of Boston [has left] since 1972.

It includes mass culture pieces — kind of branching out from film and TV — but also news stories with a significant cultural resonance like the “Big Dig” story or the Whitey Bulger story; sports, which are really important to an international city brand and certainly really important to Boston, particularly the Red Sox; music, again, something that has a resonance in pop culture in certain cities, like grunge in Seattle, for example.

“Connecting The Wire: Race, Space, and Postindustrial Baltimore” is available for purchase on Amazon.