by Rachel Richardson

513-556-5219

Aug. 2, 2017

As many as 360,000 men and women leave the military each year — good news for employers in need of the wealth of experience and skills veterans bring to the workforce.

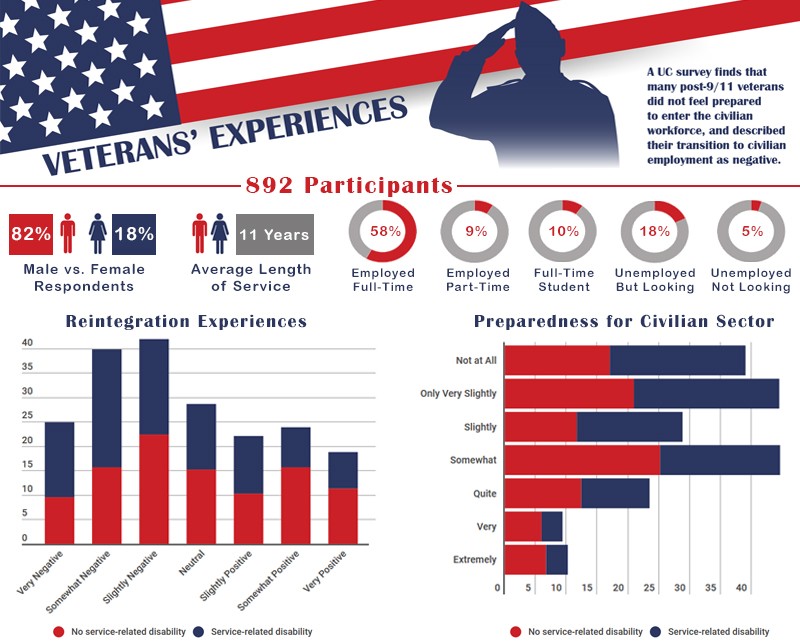

Yet, as a University of Cincinnati survey reveals, 50 percent of post-9/11 veterans without a service-related disability and nearly 63 percent of those with a service-related disability report they did not even feel somewhat prepared to enter the civilian workforce

What’s more, 48 percent of veterans without a disability and nearly 60 percent of those with a disability described their transition to civilian employment as negative.

“We know even though unemployment rates for veterans are going down, their experiences largely aren’t positive,” said Stacie Furst-Holloway, an associate professor in UC’s Department of Psychology who led the 2016 survey and will present her team’s findings Aug. 3 at the American Psychological Association’s annual convention in Washington, D.C.

A seat at the table

The research — one of the first academic studies of its kind — stems from earlier work conducted by Furst-Holloway and and a team of researchers at UC conducted with colleagues at the VHA National Center for Organization Development aimed at improving human resources practices at VA hospitals nationwide.

Data from more than 200,000 VA employees revealed that veterans there tend to be hired into lower grades despite more years of experience, are evaluated less favorably and are more likely to be demoted than non-veterans, report lower job satisfaction and leave earlier and more frequently than non-veterans.

Furst-Holloway wanted to know if these issues were unique to just the VA’s veteran workforce or if veterans in other civilian employment reported the same experiences.

But when she delved deeper, she found that while there is a sizeable research on diversity and inclusion in the workplace, much of that focuses on the experiences of women and minorities with little paid to veterans.

“Veterans represent 11 percent of the U.S. workforce. They are a substantial part of our working population yet to this point, they don’t have a seat at that table,” said Furst-Holloway.

Stacie Furst-Holloway / UC Creative Services

With help from the VA, UC’s Veterans Programs & Services office and several national recruitment firms working with veterans, Furst-Holloway launched a national survey last summer that drew nearly 900 responses from veterans of the second Gulf War — those who had served in the Armed Forces sometime since September 2001 and had returned to civilian life.

Respondents — 82 percent of which are male — hailed from all branches of the military, with an average length of service of 11 years. Sixty-two percent of survey-takers reported having a service-related disability.

Furst-Holloway and her team found that one’s length of time served in the military and rank are associated with a greater sense of preparedness for civilian reintegration, while having a service-related disability is associated with more negative reintegration experiences, feeling less prepared and a lower likelihood of being employed.

Women and those with lower levels of education are also less likely to be employed, says Furst-Holloway.

An uphill battle

Why do so many veterans face an uphill battle when returning to civilian jobs? Furst-Holloway says the problems include veterans struggling to find a good job fit for their skills, an unfamiliarity with corporate practices and expectations, difficulties in adapting to a significantly different civilian workforce culture, mental health issues and personality differences.

“Translating the skills they gained in the military to an appropriate civilian job that matches their skills and maturity level and years of work experience often has been very difficult,” she explained. “Because their resume looks different, they don’t get those jobs.”

As a result, many veterans report feeling underemployed. And those veterans who are hired often report finding it hard to bridge the gap between military and corporate culture, she said.

“One of the big issues we’re hearing from our veterans is, in the military, the culture is to do your job. If you don’t, someone will make sure that you do. There’s no slacking,” Furst-Holloway said. “When veterans come into the civilian factor, they sometimes see civilians who slack with no consequences for that.”

“It’s incredibly frustrating for people who have essentially grown up in and been socialized into an environment where that is just not acceptable,” she explained. “They don’t really know where to direct that frustration and get really fed up and they quit.”

How to climb the corporate ladder is also an obstacle for many veterans, Furst-Holloway said. Unlike the military, where there are clear lines of advancement, earning a promotion in the civilian workforce is a lot tougher jump to make.

“In the military, promotions are pretty lockstep. You know what the next level is and exactly what it is you need to do to get that promotion,” said Furst-Holloway. “Veterans come into the civilian workforce where those rules and structures often times don’t exist and get passed over for promotions.”

“Socialization into the military is so powerful. For many who join the military coming out of high school, it’s how they’ve been trained to view the world. In many private companies, it’s a very different world than what they’re used to.”

‒ Stacie Furst-Holloway

Mental health issues and personality differences, such as how resilient and optimistic a veteran is, also play a large role in how successful their transition to the civilian workforce is, said Furst-Holloway. Those surveyed who were more optimistic by nature and had a social support network reported more positive reintegration experiences and success in finding employment.

Furst-Holloway describes the survey’s findings as a “starting point” to further research on the kind of reintegration assistance veterans need most and how employers can better integrate veterans into corporate life.

“Socialization into the military is so powerful,” she said. “For many who join the military coming out of high school, it’s how they’ve been trained to view the world. In many private companies, it’s a very different world than what they’re used to.”

What veterans said

Transitioning back into work on the homefront can be a rocky road for many post-9/11 veterans. Here’s what some veterans told UC researchers about their experiences:

“One thing I have found out is that the military was easier. You knew your role and everyone else’s role. Better communication. Civilian life and work, no one knows their land and constantly bumping into mine.” E-4, Marine

“Going from a job in which I was told what to do and when to do it — and then becoming a teacher where I’m in charge of my own classroom, and it’s all up to me. This was pretty hard to get used to.” E-4, Army

“It took me eight months to find a job. Only two companies out of maybe 50 called me... The companies that say they hire veterans are all liars. Am I not capable to clean a hotel room or sit at the front desk and greet customers? To me, it was hurtful. Thank God that the GI bill helped with my rent ’cause if not, I would be in the streets with my family.” E-5, Navy

“The military instills discipline and the ability to adapt and overcome. Generally, civilians don’t have these traits. It’s very difficult to work with such entitled, self-centered and negative attitudes every day.” – E-4, Army

“Transition is hard.… It’s the attitude that is the problem with a lot of service members’ transitions. Most are vulgar, we laugh at the most horrible things, make jokes that are inappropriate.… It was our world, our coping mechanisms. It’s hard to change those things about yourself.” E-5, Army

Become a Bearcat

Learn more about how UC's psychology program is preparing graduates to work in a variety of public, private and government sectors, or explore other degrees and programs. Tour the campus and apply today.