by Mary Niehaus

The days of the "sage on the stage" are fading from the University of Cincinnati. Blackboard-framed professors no longer stand and lecture at length to note-scribbling students.

Technology-supported teaching and learning models are becoming the norm on campus and in UC "classrooms" around the globe.

A murmur of drums, flutes and tiny bells welcomes students to a class in Middle Eastern history. Large-screen video images meld into one another: mounds of swirling sand, ancient monuments, vendors of fragrant sesame and roast lamb, bearded men casting nets in a shimmering sea and women silently drowning in yards of dark cloth.

Having set the mood, the professor introduces a video interview with a woman wearing the traditional burka, who surprises the class when she speaks of what she likes about the Islamic elevation of women, how women feel so protected in her culture. Typically, the students react with disbelief or outrage.

"The video is only three minutes long, but it is the spark that triggers a lot of discussion in that classroom," says Malcolm Montgomery of Instructional and Research Computing (IRC) at the University of Cincinnati. "It's a spark that never would have kindled in a lecture. To see people talk about their culture from a personal perspective opens up students' minds and encourages them to step out of their particular parochial point of view."

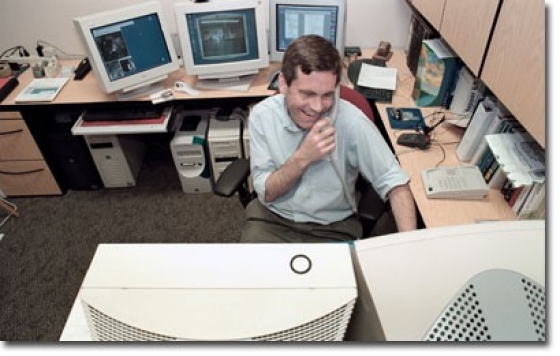

Elizabeth Frierson is showing the video in one of the university's 160 electronic classrooms, at a console that contains a computer with pen, stylus tools and Internet access; a document camera; an overhead projector; controls to raise and lower desk height, window shades, projector screens and lighting levels; and disk drives for VHS, DVD, CD and floppy. Old media horrors, such as projectors that don't arrive on time, are no longer an issue, says Montgomery, who plans the electronic classrooms on West Campus and oversees design, installation and service.

"My favorite instructors are the ones who use the technology very creatively," he says. "After the burka video, Dr. Frierson takes the students to related Web sites -- sort of teases them -- to show them what they might find in art history or where to view more video clips, then gives them assignments to pursue on their own.

"Teaching still has a lot to do with a gifted instructor or lecturer talking, drawing students out, getting them to participate -- all those kinds of human interactions, which is one reason people come to classes rather than taking them on the Web. Those interactions are fostered by having this equipment in the room."

To increase faculty members' comfort level, a simple electronic touch-screen replaces multiple remote controls at the console. "There's so much that instructors want to do that we try to hide the complexity," Montgomery says. "We present the question, 'What would you like to do?' If I'd like to show what's on the PC screen, I press the PC button, and that's what we'll get. No cables to plug and unplug, no multiple switches."

Past Issues

Past Issues