Alumni sculpt place in butter-cow history

The day the cow's udder fell off provided a valuable learning experience for UC artists: Do not sculpt a life-sized 1,000-pound butter bovine too near the door of the walk-in cooler.

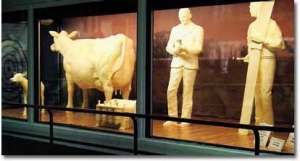

Since then, the butter sculptures at the Ohio State Fair have featured Bessie and her calf at the front of the display case. The more delicate sculptures of people have taken up residence in the rear.

It's easy to see how the mistake happened. People numb from working without gloves in a 42-degree room all day, several days in a row, could easily miss the fact that the area next to the door gradually grew a few degrees warmer the more the door opened.

One morning when the team reported to work, they discovered the truth. The weight of a dangling udder was too much for the softened butter; overnight, Bessie had become Beaufort.

Four years of sculpting the cow and company has been a continual learning experience for the three UC alumni on the team. Todd Myers, Jan LaGory and Paul Brooke travel annually from Cincinnati with three colleagues to spend a week working in the cooler.

"Nobody knows about the butter cow in Cincinnati," says Myers, DAAP '97, "but in Columbus, people nearly worship it." Indeed, the creamy critter, who made her debut in the 1920s, is such a celebrity that directional "Butter Cow" signs around the fairgrounds point guests to her abode in the Dairy Products Building.

Project design routinely starts in early July. On the Sunday before the fair's early August opening, team members move to Columbus and begin four days of continuous sculpting, approximately 250 hours. As long as udders remain in place, Thursday is mostly a clean-up day and an unveiling. Until then, no one can see through the greased glass.

Grease is certainly a prevailing danger on the job. Working with 40-pound butter bricks, sculptors with greasy hands sit and lie on the floor all day, creating an immensely slippery work environment. Although alumni have all fallen, they've carefully avoided turning sculptures into soft-spread.

The entire team holds particular admiration for LaGory, DAAP '81 -- not for his steady feet, but because he handles cold confinement so well. "I can stay in longer than most," he admits, "but three hours is probably my limit. Forty-two degrees, stretched out over an entire day, five days in a row, is really cold."

Odor is another negative condition. Those surprised that butter could stink have never smelled 2,000 pounds of it concentrated in a small enclosed area. "The first whiff in the morning is the worst," says Brooke, att. DAAP.

Originally, team members were invited to join the cow crew while employed as toy sculptors at Hasbro, a former exhibit sponsor. Today, the men mostly work independently, both professionally and at the fair. "They give us free milk shakes," Myers says. "We basically work for tips."

Perfecting their skills over the last four years, the men agree this year's display was the best, down to the milking veins popping out of the Holstein's temples. Keeping the cow and her calf company were a buttery Orville and Wilbur Wright, an airplane motor and propeller -- all historically accurate. This was "one of the most intricate and detailed displays yet," acknowledges Jenny Hubble, spokesperson for the American Dairy Association, an exhibit sponsor.

The work is a challenge, the men concede. "Butter isn't exactly prime sculpting material," LaGory points out. "Humidity condenses on it," Myers adds, "and the water keeps it from sticking properly."

Which brings up the questions, "Salted or unsalted?" "Strictly unsalted," Myers states. "Salt would create more water problems."

While the team realizes too much candor could destroy much of the cow's mystique, the alumni were willing to reveal two secrets:

- The cow is not solid butter, but butter sculpted over a wire framework that enables the critter to stand on those thin little legs.

- After the fair, butter is scraped off and discarded as rancid.

LaGory is a little hesitant to spread the word on the latter. "We prefer to let everyone think of it as Frosty the Snowman: It just melts away and is reborn the next year," he says with a grin.

Past Issues

Past Issues