Retired United States Air Force Colonel Gene Lee, in a flight simulator, takes part in simulated air combat versus artificial intelligence technology developed by a team comprised of industry, U.S. Air Force and University of Cincinnati representatives.*

Beyond video games: New artificial intelligence

beats tactical experts in combat simulation

Artificial intelligence recently won out during simulated aerial combat against U.S. expert tacticians. Importantly, it did so using no more than the processing power available in a tiny, affordable computer (Raspberry Pi) that retails for as little as $35.

by M.B. Reilly

513-556-1824

photos by Lisa Ventre,

UC Creative Services

June 27, 2016

Artificial intelligence (AI) developed by a University of Cincinnati doctoral graduate was recently assessed by subject-matter expert and retired United States Air Force Colonel Gene Lee — who holds extensive aerial combat experience as an instructor and Air Battle Manager with considerable fighter aircraft expertise — in a high-fidelity air combat simulator.

The artificial intelligence, dubbed ALPHA, was the victor in that simulated scenario, and according to Lee, is “the most aggressive, responsive, dynamic and credible AI I’ve seen to date.”

Details on ALPHA – a significant breakthrough in the application of what’s called genetic-fuzzy systems are published in the most-recent issue of the Journal of Defense Management, as this application is specifically designed for use with Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs) in simulated air-combat missions for research purposes.

The tools used to create ALPHA as well as the ALPHA project have been developed by Psibernetix, Inc., recently founded by UC College of Engineering and Applied Science 2015 doctoral graduate Nick Ernest, now president and CEO of the firm; as well as David Carroll, programming lead, Psibernetix, Inc.; with supporting technologies and research from Gene Lee; Kelly Cohen, UC aerospace professor; Tim Arnett, UC aerospace doctoral student; and Air Force Research Laboratory sponsors.

Retired United States Air Force Colonel Gene Lee, in a flight simulator, takes part in simulated air combat versus artificial intelligence technology developed by a team comprised of industry, U.S. Air Force and University of Cincinnati representatives.*

High pressure and fast pace: An artificial intelligence sparring partner

ALPHA is currently viewed as a research tool for manned and unmanned teaming in a simulation environment. In its earliest iterations, ALPHA consistently outperformed a baseline computer program previously used by the Air Force Research Lab for research. In other words, it defeated other AI opponents.

In fact, it was only after early iterations of ALPHA bested other computer program opponents that Lee then took to manual controls against a more mature version of ALPHA last October. Not only was Lee not able to score a kill against ALPHA after repeated attempts, he was shot out of the air every time during protracted engagements in the simulator.

Since that first human vs. ALPHA encounter in the simulator, this AI has repeatedly bested other experts as well, and is even able to win out against these human experts when its (the ALPHA-controlled) aircraft are deliberately handicapped in terms of speed, turning, missile capability and sensors.

Lee, who has been flying in simulators against AI opponents since the early 1980s, said of that first encounter against ALPHA, “I was surprised at how aware and reactive it was. It seemed to be aware of my intentions and reacting instantly to my changes in flight and my missile deployment. It knew how to defeat the shot I was taking. It moved instantly between defensive and offensive actions as needed.”

He added that with most AIs, “an experienced pilot can beat up on it (the AI) if you know what you’re doing. Sure, you might have gotten shot down once in a while by an AI program when you, as a pilot, were trying something new, but, until now, an AI opponent simply could not keep up with anything like the real pressure and pace of combat-like scenarios.”

But, now, it’s been Lee, who has trained with thousands of U.S. Air Force pilots, flown in several fighter aircraft and graduated from the U.S. Fighter Weapons School (the equivalent of earning an advanced degree in air combat tactics and strategy), as well as other pilots who have been feeling pressured by ALPHA.

And, anymore, when Lee flies against ALPHA in hours-long sessions that mimic real missions, “I go home feeling washed out. I’m tired, drained and mentally exhausted. This may be artificial intelligence, but it represents a real challenge.”

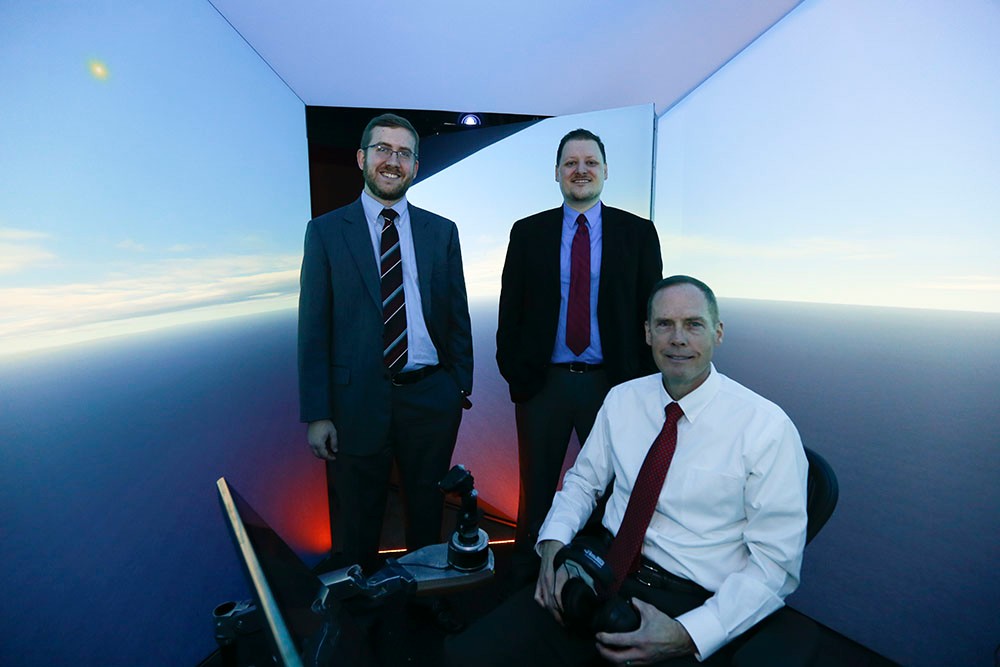

From left, UC graduate and Psibernetix President and CEO Nick Ernest; David Carroll of Psibernetix; and retired U.S. Air Force Colonel Gene Lee in an air-combat simulator.*

An artificial intelligence wingman: How an AI combat role might develop

Explained Ernest, “ALPHA is already a deadly opponent to face in these simulated environments. The goal is to continue developing ALPHA, to push and extend its capabilities, and perform additional testing against other trained pilots. Fidelity also needs to be increased, which will come in the form of even more realistic aerodynamic and sensor models. ALPHA is fully able to accommodate these additions, and we at Psibernetix look forward to continuing development."

In the long term, teaming artificial intelligence with U.S. air capabilities will represent a revolutionary leap. Air combat as it is performed today by human pilots is a highly dynamic application of aerospace physics, skill, art, and intuition to maneuver a fighter aircraft and missiles against adversaries, all moving at very high speeds. After all, today’s fighters close in on each other at speeds in excess of 1,500 miles per hour while flying at altitudes above 40,000 feet. Microseconds matter, and the cost for a mistake is very high.

Eventually, ALPHA aims to lessen the likelihood of mistakes since its operations already occur significantly faster than do those of other language-based consumer product programming. In fact, ALPHA can take in the entirety of sensor data, organize it, create a complete mapping of a combat scenario and make or change combat decisions for a flight of four fighter aircraft in less than a millisecond. Basically, the AI is so fast that it could consider and coordinate the best tactical plan and precise responses, within a dynamic environment, over 250 times faster than ALPHA’s human opponents could blink.

So it’s likely that future air combat, requiring reaction times that surpass human capabilities, will integrate AI wingmen – Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs) – capable of performing air combat and teamed with manned aircraft wherein an onboard battle management system would be able to process situational awareness, determine reactions, select tactics, manage weapons use and more. So, AI like ALPHA could simultaneously evade dozens of hostile missiles, take accurate shots at multiple targets, coordinate actions of squad mates, and record and learn from observations of enemy tactics and capabilities.

UC’s Cohen added, “ALPHA would be an extremely easy AI to cooperate with and have as a teammate. ALPHA could continuously determine the optimal ways to perform tasks commanded by its manned wingman, as well as provide tactical and situational advice to the rest of its flight.”

(Distribution A: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. 88ABW Cleared 05/02/2016; 88ABW-2016-2270)

A programming victory: Low computing power, high-performance results

It would normally be expected that an artificial intelligence with the learning and performance capabilities of ALPHA, applicable to incredibly complex problems, would require a super computer in order to operate.

However, ALPHA and its algorithms require no more than the computing power available in a low-budget PC in order to run in real time and quickly react and respond to uncertainty and random events or scenarios.

According to a lead engineer for autonomy at AFRL, "ALPHA shows incredible potential, with a combination of high performance and low computational cost that is a critical enabling capability for complex coordinated operations by teams of unmanned aircraft."

Ernest began working with UC engineering faculty member Cohen to resolve that computing-power challenge about three years ago while a doctoral student. (Ernest also earned his UC undergraduate degree in aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics in 2011 and his UC master’s, also in aerospace engineering and engineering mechanics, in 2012.)

They tackled the problem using language-based control (vs. numeric based) and using what’s called a “Genetic Fuzzy Tree” (GFT) system, a subtype of what’s known as fuzzy logic algorithms.

States UC’s Cohen, “Genetic fuzzy systems have been shown to have high performance, and a problem with four or five inputs can be solved handily. However, boost that to a hundred inputs, and no computing system on planet Earth could currently solve the processing challenge involved – unless that challenge and all those inputs are broken down into a cascade of sub decisions.”

That’s where the Genetic Fuzzy Tree system and Cohen and Ernest’s years’ worth of work come in.

According to Ernest, “The easiest way I can describe the Genetic Fuzzy Tree system is that it’s more like how humans approach problems. Take for example a football receiver evaluating how to adjust what he does based upon the cornerback covering him. The receiver doesn’t think to himself: ‘During this season, this cornerback covering me has had three interceptions, 12 average return yards after interceptions, two forced fumbles, a 4.35 second 40-yard dash, 73 tackles, 14 assisted tackles, only one pass interference, and five passes defended, is 28 years old, and it's currently 12 minutes into the third quarter, and he has seen exactly 8 minutes and 25.3 seconds of playtime.’”

That receiver – rather than standing still on the line of scrimmage before the play trying to remember all of the different specific statistics and what they mean individually and combined to how he should change his performance – would just consider the cornerback as ‘really good.’

The cornerback's historic capability wouldn’t be the only variable. Specifically, his relative height and relative speed should likely be considered as well. So, the receiver’s control decision might be as fast and simple as: ‘This cornerback is really good, a lot taller than me, but I am faster.’

At the very basic level, that’s the concept involved in terms of the distributed computing power that’s the foundation of a Genetic Fuzzy Tree system wherein, otherwise, scenarios/decision making would require too high a number of rules if done by a single controller.

Added Ernest, “Only considering the relevant variables for each sub-decision is key for us to complete complex tasks as humans. So, it makes sense to have the AI do the same thing.”

In this case, the programming involved breaking up the complex challenges and problems represented in aerial fighter deployment into many sub-decisions, thereby significantly reducing the required “space” or burden for good solutions. The branches or sub divisions of this decision-making tree consists of high-level tactics, firing, evasion and defensiveness.

That’s the “tree” part of the term “Genetic Fuzzy Tree” system.

Standing at left is UC grad and Psibernetix President and CEO Nick Ernest. David Carroll, also of Psibernetix, is standing at right. Seated at the simulator controls is retired U.S. Air Force Colonel Gene Lee.*

Programming that's language based, genetic and generational

Most AI programming uses numeric-based control and provides very precise parameters for operations. In other words, there’s not a lot of leeway for any improvement or contextual decision making on the part of the programming.

The AI algorithms that Ernest and his team ultimately developed are language based, with if/then scenarios and rules able to encompass hundreds to thousands of variables. This language-based control or fuzzy logic, while much less about complex mathematics, can be verified and validated.

Another benefit of this linguistic control is the ease in which expert knowledge can be imparted to the system. For instance, Lee worked with Psibernetix to provide tactical and maneuverability advice which was directly plugged in to ALPHA. (That “plugging in” occurs via inputs into a fuzzy logic controller. Those inputs consist of defined terms, e.g., close vs. far in distance to a target; if/then rules related to the terms; and inputs of other rules or specifications.)

Finally, the ALPHA programming is generational. It can be improved from one generation to the next, from one version to the next. In fact, the current version of ALPHA is only that – the current version. Subsequent versions are expected to perform significantly better.

Again, from UC’s Cohen, “In a lot of ways, it’s no different than when air combat began in W.W. I. At first, there were a whole bunch of pilots. Those who survived to the end of the war were the aces. Only in this case, we’re talking about code.”

To reach its current performance level, ALPHA’s training has occurred on a $500 consumer-grade PC. This training process started with numerous and random versions of ALPHA. These automatically generated versions of ALPHA proved themselves against a manually tuned version of ALPHA. The successful strings of code are then “bred” with each other, favoring the stronger, or highest performance versions. In other words, only the best-performing code is used in subsequent generations. Eventually, one version of ALPHA rises to the top in terms of performance, and that’s the one that is utilized.

This is the “genetic” part of the “Genetic Fuzzy Tree” system.

Said Cohen, “All of these aspects are combined, the tree cascade, the language-based programming and the generations. In terms of emulating human reasoning, I feel this is to unmanned aerial vehicles what the IBM/Deep Blue vs. Kasparov was to chess.”

Funding and support

ALPHA is developed by Psibernetix Inc., serving as a contractor to the United States Air Force Research Laboratory.

Support for Ernest’s doctoral research, $200,000 in total, was provided over three years by the Dayton Area Graduate Studies Institute and the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory.

Previous research

* Distribution A: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. 88ABW Cleared 05/02/2016; 88ABW-2016-2270

Distribution A: Approved for public release; distribution unlimited. 88ABW Cleared 06/23/2016; 88ABW-2016-3101.