A resident of Kotzebue, Alaska, ice-fishes from a wheelchair.

Tundra to table

UC graduate Val Kreil is helping elderly Inupiaq maintain their traditional diets in institutional care.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Val Kreil

May 3, 2018

For some residents of arctic Alaska, whale blubber and caribou are comfort foods as familiar as fried chicken, grilled cheese or mashed potatoes.

One University of Cincinnati alumnus is making sure villagers who find themselves in institutional care can continue to enjoy the wild foods they love.

Val Kreil, A&S ’78, is advocating for the rights of native people as director of a long-term care center known as Utuqqanaat Inaat, meaning “a place for elders” in the Inupiaq language, located in the coastal village of Kotzebue.

Kreil traveled to this village 35 miles north of the Arctic Circle on the Bering Sea for a temporary assignment in 2013 and decided to stay on as a full-time administrator in the Maniilaq Association, a nonprofit group that provides health care and social services to residents in Northwest Alaska.

“Kotzebue is frozen in ice most of the year. There are no roads out of town. The closest Walmart is 440 miles away,” Kreil said. “Our county is the size of Indiana but only 8,500 people live here.”

Like many rural Alaskan communities, Kotzebue is geographically isolated. Its main industries are zinc mining and fishing. Since it sits north of the Arctic Circle, it has virtually no growing season for fruits or vegetables.

“There are no chickens, no cattle here,” he said. “It’s too cold for all of that.”

Instead, people often supplement their imported groceries with wild foods, particularly fish, seal, wild game and muktuk, or whale blubber, he said. Seasonally, the waters around Kotzebue are full of salmon and a sheefish, a type of whitefish. The whaling town of Point Hope is one of Kotzebue’s nearest neighbors, albeit 150 miles away. And hunters are more than willing to share their caribou with elderly relatives, he said.

“Subsistence is their heritage. It’s their life,” Kreil said.

Kotzebue, Alaska, (pop. 8,500) sits on the Bering Sea in the Arctic Circle.

Kreil studied psychology in UC’s McMicken College of Arts and Sciences. After graduation, he worked in administrative roles at institutions around the country.

But when Kreil arrived at Kotzebue, he learned that federal law would not permit his center to serve wild foods from its kitchens. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has rules governing the types of foods that can be served at federally subsidized nursing homes. And musk oxen and caribou were not on any federal menu.

The center worked around the rules by hosting potluck dinners provided by the residents’ families. Kreil said he still remembers his first meal there.

“They had all the traditional foods. Muktuk is whale blubber. It’s chewy, like chewing cartilage,” he said. “A lot of foods are served raw because there are no trees in that part of the arctic. They wouldn’t be able to cook their meat so they would eat raw sheefish and raw salmon dipped in seal oil.”

He noticed that the residents of the nursing home seemed to relish the potluck dinners more than other meals.

“The conversation was more lively. They socialize more. And they would finish their meals. They really seemed to enjoy it,” he said. “But those were foods that were prohibited from being served in the dining room.”

Muktuk or whale.

Seal oil in mason jars.

“There is a tremendous amount of respect here for the elders. They grew up on the tundra and in the bush country. That whole lifestyle is disappearing.”

‒ Val Kreil, UC graduate and director of Kotzebue's long-term care center called Utuqqanaat Inaat

UC graduate Val Kreil

Food is an important touchstone for patients entering institutional care anywhere, said Dr. Michael Keys, a professor at the UC College of Medicine's Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience. Keys also serves as associate director for the Geriatric Psychiatry Fellowship program at UC.

“It’s a tough adjustment and food is No. 1 on the list,” Keys said. “Few places get 100 percent endorsement of their food.”

Keys said flexibility in dining hours and menus is a growing focus of patient-centered care. This often means respecting a patient’s personal dining schedules and preferred foods instead of having set mealtimes and rigid menus.

“What and when you eat is a big part of the day. So a lot of facilities are going out of their way to accommodate their patients,” Keys said.

Kreil said nurses at his assisted care center told him that the patients slept better the night after a native-foods potluck.

“That’s why it’s important to get them the foods they remember,” Kreil said.

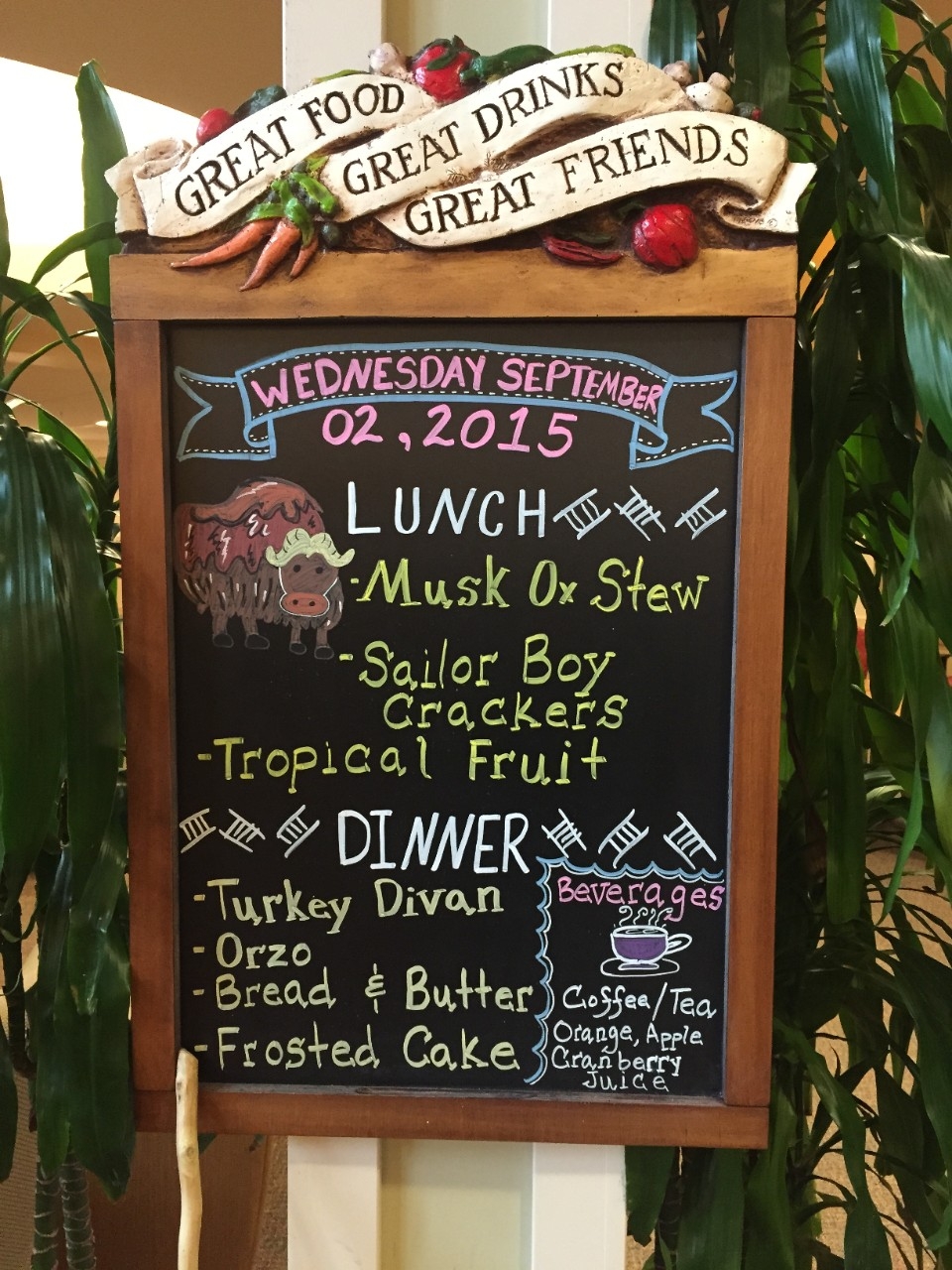

Musk ox is on the menu at the Maniilaq Association.

Life in the arctic village is similar to that in other small towns, Kreil said. They celebrate Independence Day with a parade. But there are no evening fireworks. Nobody can see them in the Land of the Midnight Sun.

Visitors to Kotzebue often get sticker shock at the high prices. A bag of chips will set you back $8. A gallon of milk costs $9.

“You learn the joys of Amazon.com,” he said.

Winters are notoriously brutal along the Bering Sea with snows so heavy and deep they obliterate roads. But on sunny days, Kreil takes the center’s residents ice fishing. A wheelchair is no impediment on the flat ice.

Former President Obama made a historic visit to Kotzebue in 2015. Kreil said the entourage borrowed every van at his center for a tour of town.

When Kreil started working in Kotzebue, he learned how much interest there was by staff to serve native foods to the elders in their care.

Kreil said the U.S. Department of Agriculture has provisions for the inspection of wild game so that it can be served just as domestic beef is at an institution. But getting wild game inspected by a USDA-certified butcher in the arctic was impractical, if not impossible. The USDA also did not have any provisions for the slaughter of wild game such as moose, caribou or musk ox.

Likewise, traditional diets in the arctic are much higher in animal fats with comparatively fewer fruits and vegetables than regulators consider necessary for a healthy, balanced diet. It’s an adaptation to living in such an extreme environment.

The state Legislature recognizes that subsistence hunting is a big part of Alaska’s culture and economy. Kreil spoke with Alaska’s Department of Environmental Conservation and the USDA to determine who had oversight over donations of meat derived from wild game such as caribou and musk oxen. After answering questions to their satisfaction, federal regulators deferred oversight to the state.

“Alaska’s regulations are progressive and allow you to donate wild game to institutions,” Kreil said.

Young people in Kotzebue participate in an Independence Day parade.

An elderly resident of Kotzebue, Alaska, cleans a fresh salmon.

Residents of Kotzebue, Alaska, turn out for the annual Fourth of July parade.

A year after Kreil arrived in Kotzebue, Congress amended the Farm Bill to allow tribal facilities to serve traditional foods as long as wild game is processed by certified butchers.

Perhaps the best part today, Kreil said, is that hunters give their names when they donate so the patients at the center know whose generosity is filling their tables, he said.

“There is a tremendous amount of respect here for the elders. They grew up on the tundra and in the bush country. That whole lifestyle is disappearing,” Kreil said. “Kids today have iPhones and iMacs. When we do the Fourth of July festival, they’ll set up a tent for us at the fairgrounds. People will come up and shake the elders’ hands and say who their mothers and fathers are.”

Today, the Maniilaq Association has its own meat processing center for fish and wild game. Alaska expanded the definition of native foods to include tundra staples such as high-bush cranberries and alpine blueberries, which means centers can serve these foods from tundra to table as well, he said. And they have a hydroponic greenhouse in the community that grows lettuce and, perhaps one day, will grow native edibles such as the chard-like plant called sourdock, he said.

And he’s working with state regulators to get approval later this year to serve seal oil, which is an all-purpose condiment in the arctic.

Seal fat takes days to render into oil, he said.

“It’s like watching ice cream melt,” he said. “You stir it twice a day and it breaks down.”

Prepared incorrectly, the oil can harbor the bacterium that causes botulism. But Kreil said he is working to demonstrate that seal oil can be prepared safely so the center can obtain a variance.

“My role as an administrator is solving problems. How do I meet the needs of elders and improve their quality of life?” Kreil said. “Fortunately we’ve been able to make this work.”

A girl in Kotzebue, Alaska, takes part in a traditional Eskimo blanket toss as part of a summer festival.

Follow your heart

UC graduates strive to make a difference in the world. Check out the Department of Psychology in UC's McMicken College of Arts and Sciences or explore other programs on the graduate or undergraduate level.