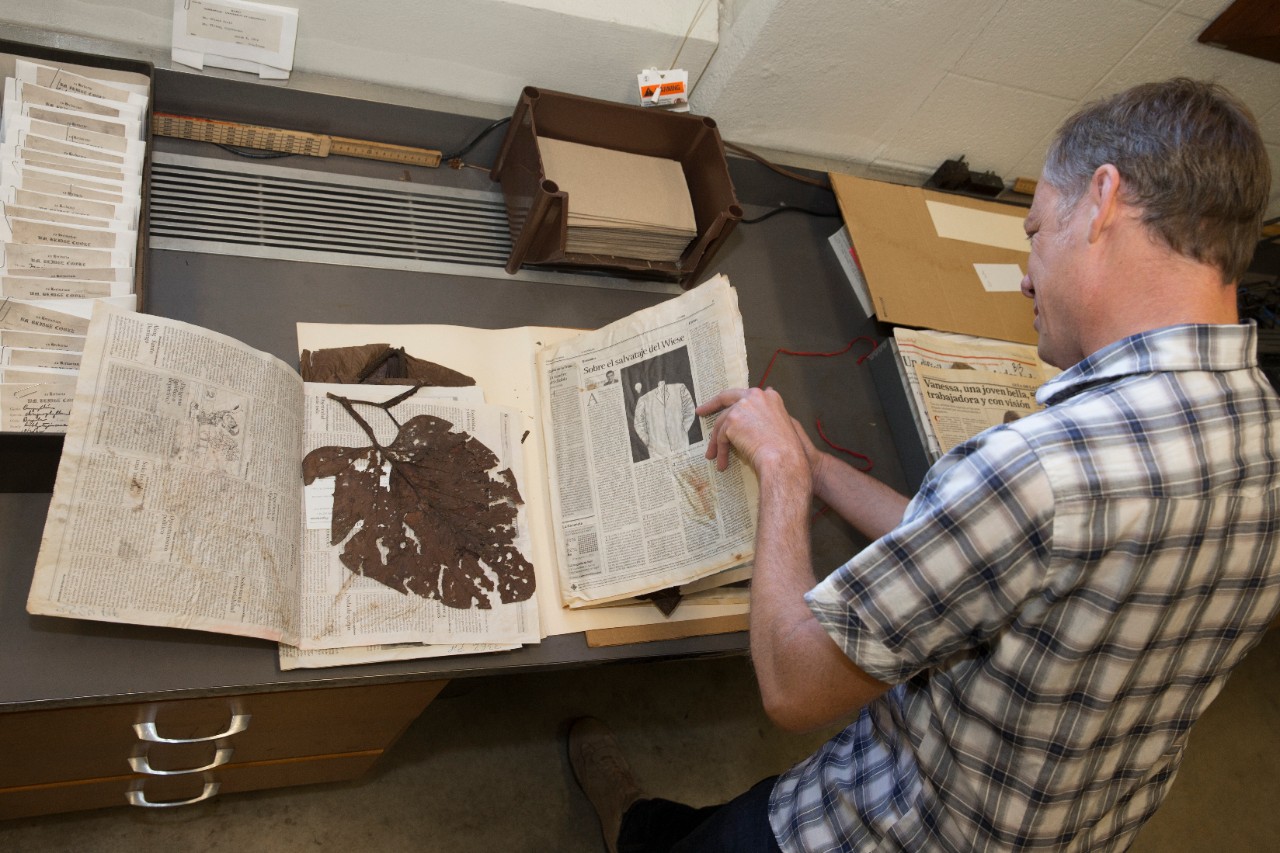

UC biology professor Eric Tepe demonstrates how to preserve plants in the Margaret H Fulford Herbarium.

The Taxonomist

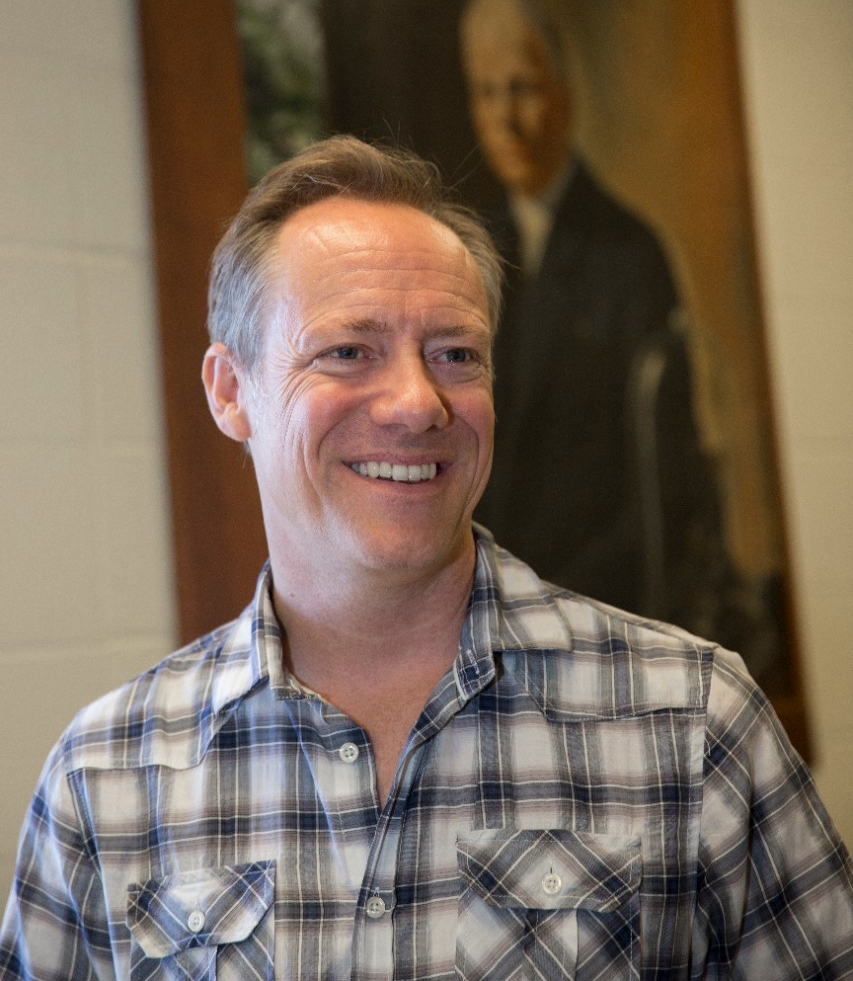

Biology professor Eric Tepe is leaving his mark on botany with new discoveries at UC's herbarium.

By Michael Miller

513-556-6757

Photos by Lisa Ventre/UC Creative Services

Oct. 20, 2017

Eric Tepe remembers the class that inspired his work as a botanist at the University of Cincinnati.

His first botany professor at Ohio State University, the late William Jensen, dressed up like Indiana Jones, from the fedora and leather jacket right down to the bullwhip.

“His point was we’re going to travel the world. We’re going to explore the wild world of botany,” Tepe recalled. “So who’s going to forget these things?”

Tepe surely didn’t.

Today, the assistant professor of biological sciences in the McMicken College of Arts & Sciences tries to inspire his own students at UC to learn firsthand about the natural world, minus the costumes.

“I don’t have the guts to do that stuff in class – yet,” he said.

But just as in “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” new botany discoveries often begin with library research. And at UC, that means the plant library that Tepe curates, the Margaret H. Fulford Herbarium.

A freshly dried specimen is ready for cataloguing at UC's herbarium.

UC biology professor Eric Tepe reacts after smelling a pepper plant.

This botanical treasure-trove hidden within a nondescript lab atop Crosley Tower has inspired some of UC’s most exciting biological discoveries. UC safeguards a collection of more than 125,000 dried and pressed plants from around the world — some plucked decades before the Civil War and others new to science.

The herbarium represents an important resource for botanical research, Tepe said.

“Every specimen is unique and, in a sense, irreplaceable. It’s a historical and geographic record of what’s where and when,” Tepe said. “You can track the shrinking range of native plants or the expanding range of invasives or exotic species.”

UC’s herbarium is more a lab than a library. Researchers use the herbarium to unearth nature’s mysteries — and then go about solving them.

To date, Tepe has five plant discoveries to his name. More recently he identified four additional plant species new to science in Ecuador and Panama that he plans to submit to research journals.

“We as a species are obsessive cataloguers and namers. It's an innate thing we do. We want to make sense of our world.”

‒ Eric Tepe, UC botanist

The method for preserving plants has not changed much since 1532 when the oldest known collection of plants was preserved in Italy. UC botanists press the plants between sheets of paper and cardboard.

While poring over UC’s plant collection, Tepe sometimes finds specimens that don’t match his expectations or other scientific accounts. Using century-old field notes scrawled on yellowed paper, Tepe tries to track down these same species in the wild.

Tepe discovered a new species of black pepper, Piper kelleyi, that grows in the Andes of Ecuador. The plant, nicknamed “pink belly” for the rosy undersides of its leaves, is host to at least 40 species of insect, including 11 caterpillars that depend on it. Tepe named it for his botany colleague and Piper enthusiast, the late Walter Almond Kelley of Colorado.

“That discovery started in the herbarium. In fact, most discoveries do,” Tepe said.

As a botanist, Tepe has explored Central and South America. He grew up in Toledo but as a child spent years living Venezuela and Argentina and speaks fluent Spanish.

In place of Indiana Jones’ revolver, he keeps a pair of durable pruning shears handy in a leather holster on his hip.

He works with Solanum, a genus with more than 1,500 species, including some of the world’s most valuable crops: potatoes and tomatoes.

Taxonomy – or the science of naming and classification – is one of his specialties.

“We as a species are obsessive cataloguers and namers. It’s an innate thing we do. We want to make sense of our world,” he said.

Eric Tepe

“Rarely do you uncover something and say, 'Wow, that's different!' More often, it's confusing and frustrating for a while. Why doesn't this fit?”

‒ Eric Tepe, assistant professor of biological sciences

Tepe found three new species of Solanum while exploring Ecuador in 1994. He named one of them, Solanum pacificum, after the Pacific lowlands where it was found but also in tribute to his wife and frequent field partner, UC professor Maria Paz Moreno, who teaches Spanish in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures.

“She is super in the field. She works as long days as I do and is a pro at pressing plants,” he said.

Tepe uses his phone to record field notes and, importantly, GPS coordinates for each specimen. This is especially helpful when it is time to catalog what he finds back at the herbarium.

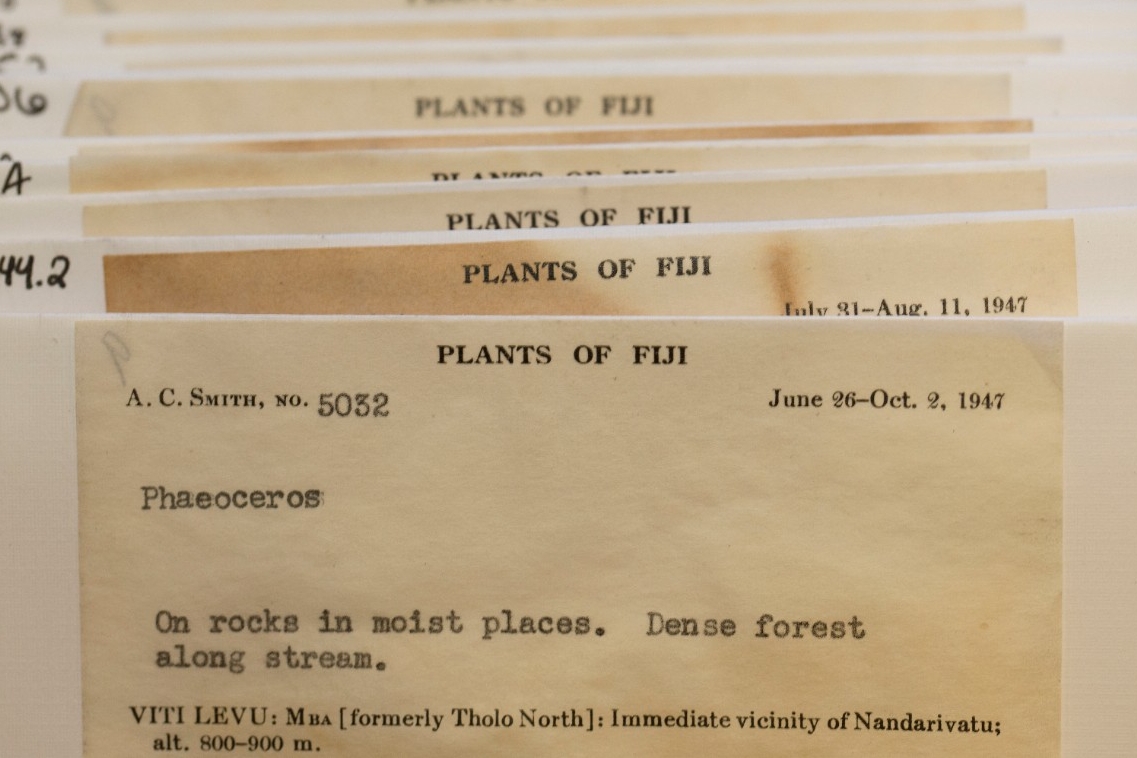

Plants are stored alphabetically by family name in folders color-coded by continent with labels identifying where and when they were collected and by whom. The folders are kept in rows of waterproof cabinets.

Botanists preserve plants the same way they have for centuries. They arrange them between sheets of paper — often newsprint — which are pressed between cardboard bound together in a wooden frame.

“Any paper will work but newspaper is cheaper,” Tepe said. “Using recycled paper goes all the way back to Capt. James Cook and botanist Joseph Banks. They had misprints of ‘Paradise Lost,’ I think, that they used on their voyage to collect plants in Australia during their voyage around the world.”

Plants of Fiji in UC's collection.

Leaves of three: poison ivy.

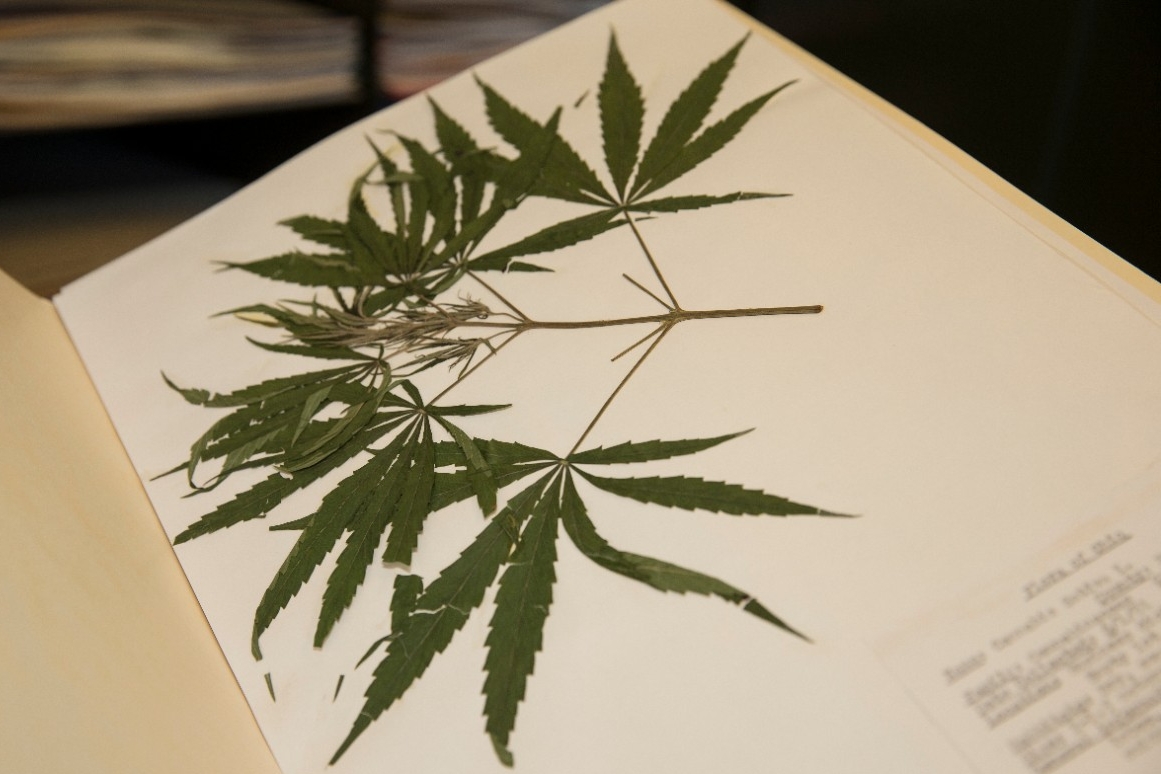

Cannabis collected in Cincinnati.

In UC’s herbarium, botanists store presses full of fresh specimens in a cabinet dryer overnight. Then they take the dried plant and glue them to a piece of acid-free paper where they can last for centuries.

Tepe removed a sundew, a carnivorous plant, with a label written neatly in cursive: New Jersey, 1836.

“It’s incredible, isn’t it? We have a lot from the late 1800s,” he said.

The UC herbarium’s namesake, Margaret Fulford, was its first curator beginning in 1927, although the collection is believed to have started much earlier. UC also has plants collected by Cincinnati pharmacists John, Nelson and Curtis Lloyd, collectively known as the Lloyd brothers, who also have a downtown Cincinnati museum and library in their name.

“We have one of the first large collections of Samoan flora, thanks to one of the Lloyd brothers’ wanderlust and, I’m guessing, Curtis’ dislike of Cincinnati winters. He spent two winters in Samoa in 1904 and 1905,” Tepe said.

Tepe pulls out another one. Its leaf pattern is instantly recognizable: cannabis. Tepe reads aloud the label location: Business district, Vine Street. Empty lot. 1981.

“We also have a (cannabis) specimen collected by Curtis Gates Lloyd in Clifton dated 1877,” he said. “So things haven’t changed that terribly much around here, I guess.”

When it comes to understanding what treasures are held in its collection, Tepe said UC is just getting started.

“My pipe dream is to have a fully renovated space in Rieveschl Hall that is like a fishbowl so passersby can see what’s going on inside — exhibit space to draw people in and to show them what goes on in an herbarium,” he said.

Eric Tepe sorts plants for preservation after a day of collecting outside the Yanayacu Biological Station in Ecuador. (Provided)

UC professor Eric Tepe discovered and named this species of wild pepper, Piper kelleyi, nicknamed "pink belly." (Provided)

Herbaria regularly share their specimens with researchers at other institutions. The world’s largest herbarium in France (with an estimated 70 million specimens) made international headlines this year when Australian customs officials intercepted and incinerated some of its specimens from the 1700s destined for botanists in Brisbane. The shipment allegedly violated the island nation’s strict quarantine protocol.

Sharing is easier and more common as places such as UC begin to digitize their collections, photographing and cataloging specimens in online databases. Tepe won a National Science Foundation grant to photograph and create a digital archive UC’s collection of mosses, hornworts, and liverworts, which are kept in small envelopes and filed in cabinet drawers like the old card catalogs in libraries. The photos and specimen details are uploaded into a massive database shared by botanists worldwide.

UC still has tens of thousands more plant specimens to photograph and catalog for its digital archive.

“They’ve been locked up here in some cases for as long as 180 years. Unless someone visits in person and happens to find them, nobody will ever know they’re here. But our digitization project is changing that,” he said.

Already, researchers have taken advantage of UC’s digital collection, he said.

“We’ve made more than 43,000 specimens available online,” he said. “The database has been used to compile larger datasets. And several people who have published papers using our collection have never been here.”

UC graduate Samantha Al-Bayer volunteers at the herbarium, where she presses flowers and ferns to create artwork. "People look at them and ask, 'Is that a painting?'" she said.

UC graduate Samantha Al-Bayer, 25, is volunteering at the herbarium where she studied botany as a student. Besides helping with the collection, Al-Bayer turns her own flower pressings into framed art. For example, she framed wildflowers over a piece of sheet music or combines ferns and flowers in an arrangement like an oil painting.

Al-Bayer said her artwork helps people appreciate what they might take for granted every day.

“Everything we eat, drink or write on is plant-based. I just want to show people how interesting and amazing plants are,” she said.

Tepe said UC’s collection has plenty of potential to grow. And he hopes to inspire his own students to follow their own curiosity to the unexplored fringes of the world. But they can leave the swashbuckling at home.

“I try to keep my research trips from becoming adventures,” he said. “When they become adventures, that means something has gone totally haywire somewhere.”

Eric Tepe examines a wild coca plant (Erythroxylum coca) in Chanchamayo, Peru. (Provided)

Contributing to science:

UC botanist Eric Tepe has discovered nine species of plants new to science, including five recognized in academic journals:

Piper kelleyi

Discovered in the Andes of Ecuador, this plant nicknamed “pink belly” for the rosy undersides of its leaves, is host to at least 40 species of insect, including 11 caterpillars that depend on it. Tepe named it for his botany colleague and Piper enthusiast, the late Walter Almond Kelley of Colorado.

Solanum baretiae

Tepe named this wild potato from Peru after French botanist and explorer Jeanne Baret, the first woman to sail around the Earth. Baret accompanied naturalist Philibert Commerson on a 1766 expedition but posed as a man to dodge French naval regulations and tradition forbidding women aboard ships. She belatedly was credited with many of the voyage’s scientific discoveries, including the popular ornamental vine Bougainvillea, named in honor of the expedition’s captain. But Tepe’s discovery was the first formally named for her.

Solanum pacificum

Tepe described this in a 2009 research paper with University of Utah collaborator Lynn Bohs. He named it after Ecuador’s Pacific lowlands where it was found and also in tribute to his wife and frequent field partner, UC professor Maria Paz Moreno, who teaches Spanish in the Department of Romance Languages and Literatures.

Solanum crassinervium

Found in one of the most biologically rich parts of Ecuador and Colombia, this plant was named for its prominent leaf veins.

Solanum limoncochaense

Named for the Reserva Biologica Limoncocha where it was found in Ecuador, this species and pacificum were found only in small reserves and could be in critical danger of extinction.

UC biology professor Eric Tepe stands in front of a cabinet full of botanical specimens in the herbarium.

Field research to labwork

Do you like field research? At UC, biology students get hands-on experience in their chosen subject area. Check out the Department of Biological Sciences or explore other programs on the undergraduate or graduate level.