Unbound

UC helps former heroin addict develop global leadership skills and find himself

Dec. 18, 2014, marked a decade since Cory Murphy stopped using drugs.

“10 years clean.”

The brief message spelled out in blue stick-on letters atop Cory Murphy’s red mortarboard said so much. Yet it’s only a hint of this former addict’s story.

It was December 2014, and Murphy, a Carl H. Lindner College of Business grad, walked across the stage at the University of Cincinnati to receive his bachelor’s degree with distinction and honors. It had been an incredible journey since life crashed down around him 12 years earlier.

"I remember waking up once and looking around at all the other addicts, as everyone in the room was high on something,” says Murphy. “But as the spinning walls began to slow down, I remember thinking that I'm not really like these guys –– I could have a future."

Before his addiction to heroin, Murphy, a rural Pennsylvania high school football center and honor student, was on his way to achieving the rank of Eagle Scout, the highest award achievable as a Boy Scout. He had lofty plans to go to college and to do great things. But at the end of his junior year in high school in 2002 it all came tumbling down.

“It was subtle really,” says Murphy. “I didn’t plan on getting hooked on something that would pull me down like that, I just wanted to ease the pain. Because I wore long hair in high school, I was called names and bullied to the point of contemplating suicide. But once I experienced the phenomenon of morphine from shoulder surgery, I discovered a new world of opiates, and that became a way to escape.”

When his prescribed painkillers ran out, he started abusing pills from the family medicine cabinet and shared them with his friends. When his home reserve was gone, he started buying pills and then went on to heroin.

Cory Murphy when he was using heroin as a junior in high school in 2002.

Murphy, years after getting clean, speaks to a class of students as president of UC's International Business Club in 2013.

“Snorting heroin was still infrequent enough that I felt there was no danger of it becoming a problem,” says Murphy. “And many of the popular kids were doing it, so I finally found a way to really fit in. But the addiction eventually snuck up on me."

Heroin was becoming a full-blown epidemic in Butler, Pennsylvania, and he was fully caught up in it.

Changing tides

Murphy’s world was changing, and his identity was shifting. The emotional anguish and pain from his shoulder surgery were deadened, but his dependence on the relief was growing.

In the early days of his addiction, he lived in dual worlds –– supervising his Eagle Scout project by day and getting high with his new friends by night.

Though some of his friends landed in jail when they were busted for stealing to support their habit, Murphy stayed out of trouble until he was accused of selling pot at school.

The honor student, starting football player and Eagle Scout found himself expelled from school at the end of his junior year.

“It was one of the greatest things that ever happened to me,” says Murphy. “I was finally free of that cesspool of a school. All of the bullies were gone from my life. And the teachers who watched the bullying but never did anything about it were also gone. Bullying had been a major problem and using drugs helped me cope.”

Still, things spiraled downward for Murphy, and his drug use increased.

“My mom had instilled in my head that if I got into trouble, my chances of getting into college would be ruined,” Murphy said. “So here I was, no school and no diploma. It was game over for getting into college –– so I thought.”

His future looked as dark as the circles under his eyes and even more so after a friend convinced him to shoot up instead of snort his heroin.

“What a rush,” says Murphy. “Shooting up was a lot cheaper and a much better high, an immediate blast from sobriety to euphoria. It suddenly made much more sense to use a needle.”

Cory Murphy before he was expelled from high school.

Murphy now works in GE Aviation's Operation Management Leadership Program in Cincinnati.

Cory Murphy being recognized as a Presidential Leadership Medal of Excellence Award winner during May 2015 commencement at UC. Photo/Joseph Fuqua II

Working in fast food gave Murphy the cash flow to fund his habit. And as fate would have it, the same business sense that now brings him legitimate success began to rear its head back then. He discovered the profits he could turn by buying cheap in inner-city Pittsburgh and selling for double or more in rural areas.

“The gang members in the hood wouldn’t hurt or rob you if you were their customer,” says Murphy. “They actually welcomed my friends and me with open arms when we drove up, even at 2 a.m. in the worst part of the city.

“I provided a service, and for that I never had to pay for drugs out of my own pocket.”

By 2003, the access to needles, the new incredible high and the financial gains were leading him down a path that could have spiraled completely out of control. But soon after a breakup with his girlfriend and a near emotional breakdown, Murphy looked for a professional to talk to about the pain he carried. His mother, still unaware of his drug use, suggested he see a chiropractor friend for therapy.

Murphy could conceal his track marks under his hoodie sleeves, but his observant doctor noticed the telltale signs of heroin use in his sallow complexion and sunken eyes framed in dark circles, and quickly intervened.

“My doctor looked at my mother and said, 'You’ve got to do something, and you’ve got to do it now,'" says Murphy. “'I recommend he go to a rehabilitation facility, a good one, and one that is away from here, away from his environment and friends who represent a constant reminder.'”

Within days, his mom raised the money, and Murphy was on a plane to Clearwater, Fla., to an experience that opened his eyes to new possibilities.

International co-op experiences gave Murphy an opportunity to see the world, including this scene with a fellow UC student in Istanbul, Turkey.

Murphy at work as a co-op for GE Aviation in Germany.

Hope and hard work

During rehab, Murphy worked out daily and ran along the beach. He learned mental coping skills, ate healthier than he had in many years and began to purge the drug’s toxic effects through daily sauna and steam baths.

After several weeks, he was able to return home to a new beginning, but within a few hours of being home, Murphy allowed himself to be lured by one of his friends into shooting up again.

“In a matter of months, I was back in Florida for the second and last rendezvous with therapeutic intervention,” says Murphy. “And after this jolt back to reality, I finally felt myself mature a little more each day. I knew at once that the only way to stay clean was to leave my hometown and make a fresh start.”

Finally clean from drug use in 2004, Murphy moved to Covington, Ky., and started performing outreach for drug addicts through a church program. It was the start of a three-year journey of turning his own life around by helping others.

He worked close to 100 hours a week ministering to recovering addicts, but eventually the lack of a real salary, living in dangerous neighborhoods and using food stamps to get by began to take its toll. Plus, Murphy knew there was a better way to make an impact.

“I thought about how many more people I could reach if I had a college degree and a positive network. But I had no computer, no Internet, no car and no adequate wardrobe.

‒ Cory Murphy

“I thought about how many more people I could reach if I had a college degree and a positive network,” says Murphy. “But I had no computer, no Internet, no car and no adequate wardrobe.”

While searching through UC’s website, he stumbled upon the Presidential Leadership Medal of Excellence Award. He immediately knew this would become his new goal –– his red and black badge of courage.

“When I saw the medal, I knew I finally had a target –– it’s the highest award a student can receive. I knew that if I could earn that medal when I was ready to graduate, it would mean that I had accomplished something as a student.”

At age 24, and five years clean from drug use, Murphy secured student loans and entered the Lindner College of Business in 2009.

“It was a motivating experience for me because I had the opportunity to do what neither of my parents had done at the time, to earn a bachelor’s degree,” says Murphy. “I just knew in my heart that this new college life was meant to be, and with hard work and determination I would be successful.”

Murphy poses with UC President Santa Ono prior to commencement in May 2015.

His tenacity fueled his success through the next five years, and he took advantage of nearly every opportunity in front of him.

In his first year at UC, Murphy won nine scholarships and joined six student organizations, including the International Business Club where he served as president all five years. During his sophomore year, he won the Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship from the U.S. State Department allowing for a full ride to study in Istanbul, Turkey, where he fell in love with the idea of global operations management.

“One night while studying for finals, I looked out over the bridges that literally connect the continents of Europe to Asia,” Murphy says. “I just stared at the hundreds of logistics companies going back and forth, each truck with a different language written on it. And I thought to myself, ‘this is the blood of business.’

“I now knew I didn’t want to be the one counting the numbers that someone else had created, I wanted to be the one who actually drove those numbers making the business better.”

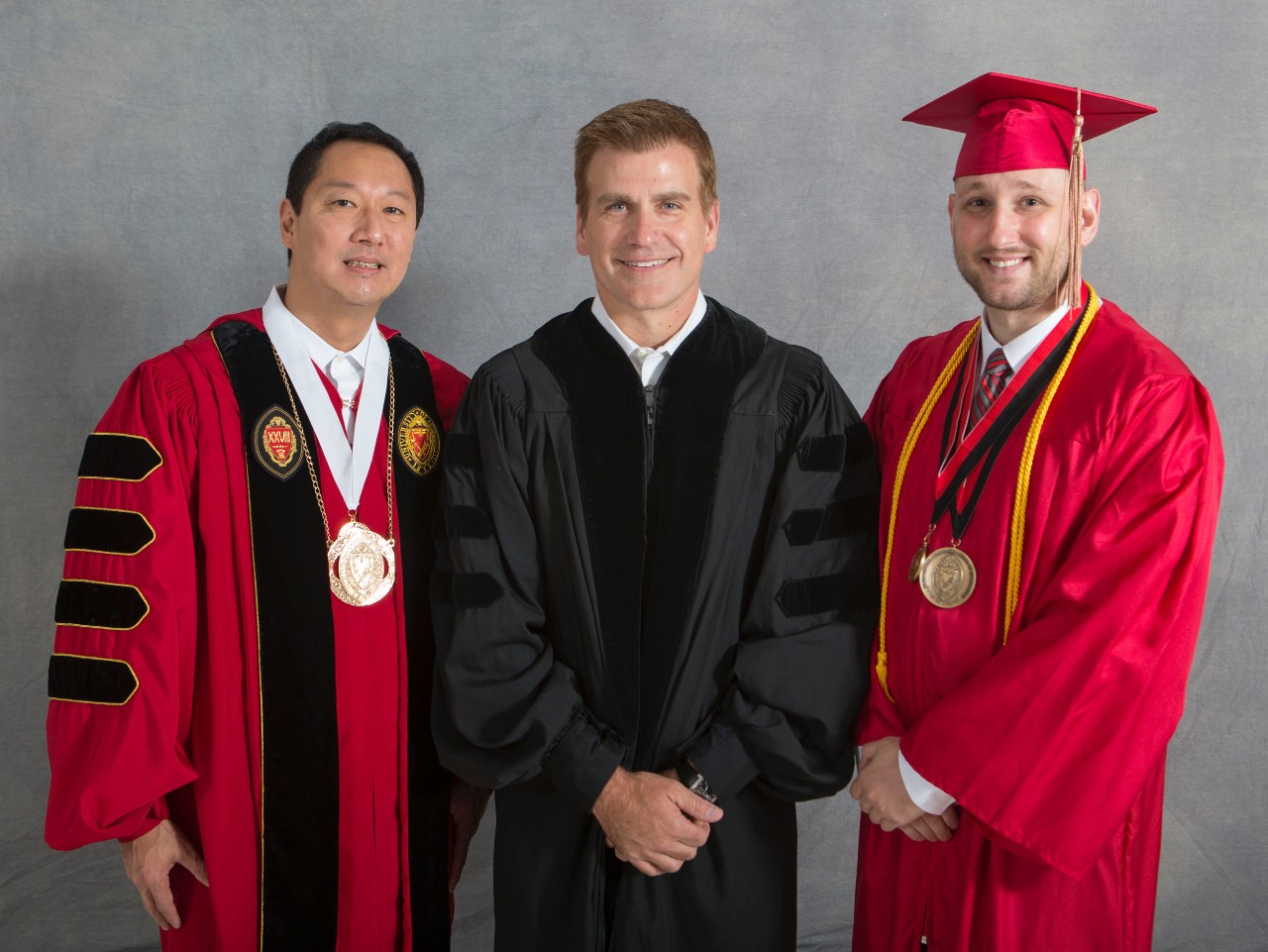

Murphy (at right) with UC President Santa Ono (left) and commencement speaker Kirk Perry, Bus '90, HonDoc '15, president of brand solutions at Google.

Once back at UC from his international co-op, he switched his major to operations management and international business, and he resumed his leadership of the International Business Club. He arranged weekly speakers and cultural experiences highlighting such places as Ethiopia, Japan and West Africa. This initiative led to the club being nominated for the Campus Life Award for Diversity by UC’s Student Activities Board.

It was one of many honors for Murphy, a student with a past that floored those who got to know him on campus.

“To say I was surprised to learn about Cory’s past drug addiction would be a gross understatement,” says Raj Mehta, vice provost for UC International Affairs and director of the University Honors Program. “During the four years I worked with Cory, I saw a strong, motivated student who was a disciplined leader, and with no indication that he had not always been so.”

Leveraging leadership skills

Inspired by UC President Santa Ono’s Third Century Initiative to double the number of students to study abroad by 2019, Murphy piloted the International Club’s Early Exposure Program, an effort to reach out to high school students and plant the seeds for applying early for an international college experience.

“I had noticed a trend of students who were nearing graduation with a great regret for never having studied abroad,” says Murphy. “They cited a lack of awareness as being the sole reason, so I didn’t have to hear any more.”

In his fourth year, he went on to spend two semesters in Regensburg, Germany, as a co-op for General Electric Aviation. There he supervised more than 60 shop-floor workers, all the while communicating entirely in German.

“GE does not typically support international co-op assignments, but I was able to leverage my internal network to create a position for myself in Regensburg,” says Murphy. “I later found out that my father’s family had originally immigrated to the United States from that very town. So it felt like home.”

Murphy celebrates his gradution with his parents Ken and Donna Murphy.

Though Murphy graduated from UC in the winter of 2014, he returned to the commencement ceremony in the spring of 2015 to receive that coveted Presidential Leadership Medal of Excellence Award, as one of only six awardees from a class of more than 6,300.

“What intrigued me the most about Cory was that he didn’t use his experiences to gain access or sympathy,” wrote Ruth Seiple, professor in the Lindner College of Business, in her nomination letter for the award. “He has found a way to build upon and appreciate his tough life lessons, that for many would have sidelined them at the minimum, and at the worst, taken them out of the game altogether.”

Murphy now works full time in GE Aviation’s Operation Management Leadership Program in Cincinnati, and he is considering a graduate degree in business.

“I don’t even think about heroin anymore. I can’t even remember the last time I did,” says Murphy. “The rush I get from being successful trumps any feeling a drug could ever give me.”

“The most treasured wisdom I’ve gained from UC and my whole whirlwind experience is that the best ‘high’ in the world is the feeling of great achievement.”

Melanie Schefft

Melanie is a contract writer with the University of Cincinnati and a contributor to UC Magazine.

mellkshefft@yahoo.com