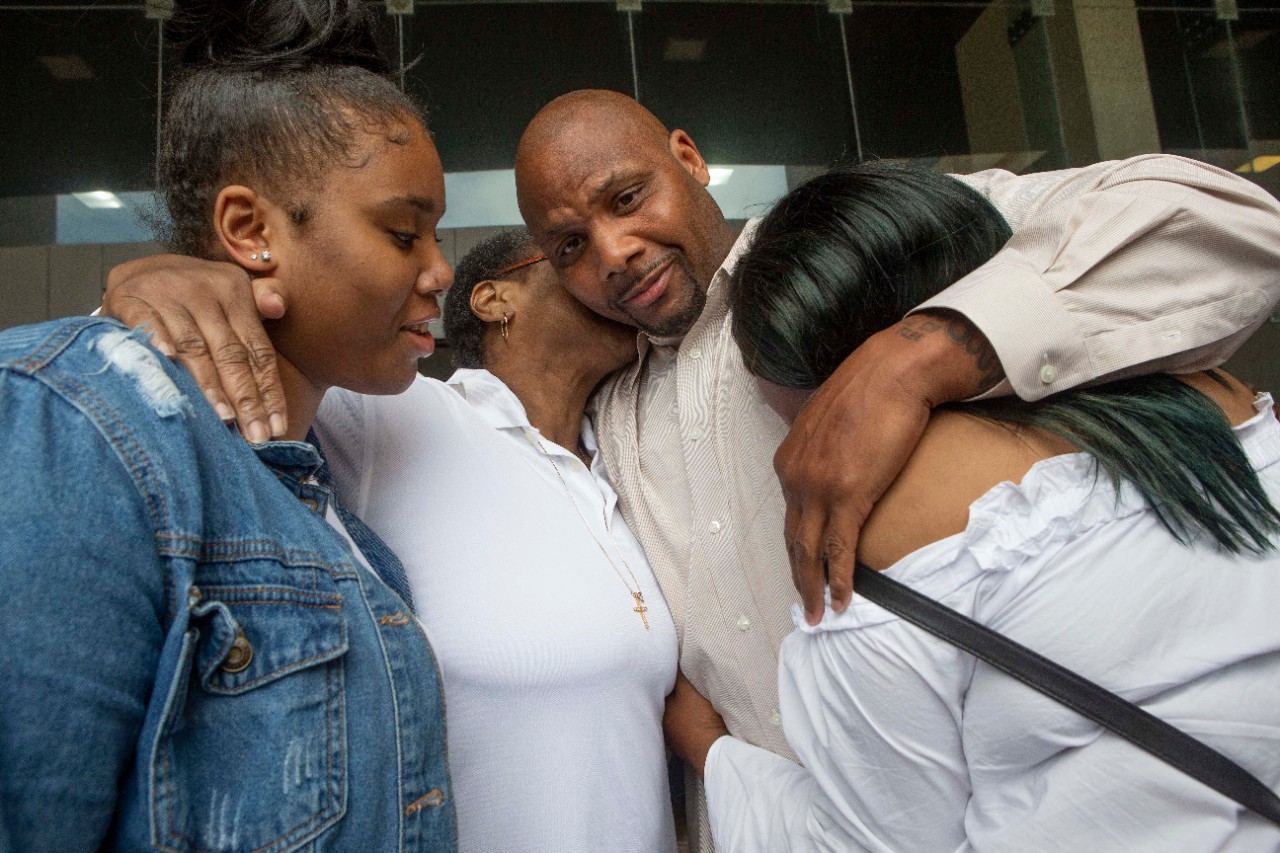

Christopher Miller hugs his daughters De'Nazha, left, and Chareale on Thursday outside the Cuyahoga County Justice Center. Miller was exonerated with help from UC's College of Law after spending 17 years in prison for crimes he did not commit.

UC proves another innocent

A Cleveland man convicted of a rape he did not commit was released from prison with help from UC's College of Law. The case marked the 27th defendant whose wrongful conviction was overturned with the help of UC students and faculty.

By Michael Miller and Rachel Richardson

513-556-6757

Photos by Joseph Fuqua II/UC Creative Services

June 21, 2018

CLEVELAND – An Ohio man who served 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit was exonerated and released Thursday with help from University of Cincinnati law students and their professors.

The Ohio Innocence Project, part of the UC College of Law's Lois and Richard Rosenthal Institute for Justice, took up the case of Christopher Miller, 41, who was convicted of the kidnapping, aggravated sexual assault and robbery of a woman in Cleveland Heights in 2001.

Students and faculty at UC’s College of Law took up the case in 2015. It marks the 27th defendant freed with help from the UC College of Law’s Ohio Innocence Project.

An ebullient Miller left the Cuyahoga County Courthouse to cheers from family and supporters.

"My baby's home," his mother said, hugging and kissing him.

"It's been a long time coming," Miller said.

UC College of Law professor Brian Howe addresses the court Thursday on behalf of client Christopher Miller during a hearing over a motion to vacate charges. Howe works on the College of Law's Ohio Innocence Project, which to date has helped free 27 defendants wrongly convicted of crimes.

Miller was sentenced to 40 years in state prison for an attack that left the victim so traumatized that she told the court she sleeps with the lights on and can’t go into her own home by herself at night.

Miller always maintained his innocence and offered an alibi — he was asleep with his girlfriend miles away when the assault occurred. But police investigating the assault tracked the victim’s cell phone to Miller, who said he bought it from a local drug dealer.

A second suspect, Richard Stadmire, also was arrested and convicted in 2002.

A third suspect in the case, Charles Boyd, testified that Miller was an accomplice in the crime. Miller maintained that Boyd was lying and that they had never met. Boyd later recanted his testimony.

Prosecutor Michael O'Malley on Thursday said a grand jury this week indicted Boyd on new charges of rape and perjury in the case.

Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court Judge Hollie Gallagher ordered that the convictions against Miller be vacated and that he be released immediately.

Family members of Christopher Miller react to the judge's ruling ordering charges to be vacated and Miller's immediate release after serving 17 years in prison.

Family members in the courtroom gallery smiled, hugged and offered high-fives to each other after the judge rendered her decision. They said they never lost faith that Miller one day would be proven innocent.

Chareale Miller, 23, the oldest of three children, was only 5 when her father was arrested. She said they missed so much not having their father in their lives.

“Birthdays, Father’s Days, graduation, prom — I missed him so much,” she said.

Miller stayed in touch with phone calls and videos he would send electronically. But in-person visits were infrequent since he was detained at the Richland Correctional Institution in Mansfield.

Chareale Miller said she helped to look after her younger siblings, Christopher Miller Jr., 18, and De’Nazha, 17, in their father's absence.

Miller was lead into the courtroom wearing an orange prison jumpsuit, shackles and chains.

Cuyahoga County Assistant Prosecutor Anthony Miranda asked the court to vacate the convictions against Miller. He said new DNA tests conducted at the behest of the Ohio Innocence Project disproved the state’s theory in the crimes.

After his incarceration, friends and family started an innocence blog on Miller’s behalf. They posted testimonies about his character and offered their public support.

“I wish my dad can come home. I don’t like the long drive we take to visit him and I don’t like to leave him at that jail alone. Please help my dad come home,” Chris Miller Jr., now 18, wrote in a 2008 post.

Sheriff's officers lead Christopher Miller into court Thursday in an orange prison jumpsuit, shackles and chains. Hours later, he left the courthouse with his family – exonerated of all convictions.

Among supporters in the courtroom gallery were several Ohio Innocence Project exonerees. Since their release, many in this circumstantial fraternity have stayed in close contact with each other and UC professors and students.

“We’ve been there. We are the only ones who know what they’re going through,” said Dean Gillispie, who was released in 2011 after serving 20 years for a crime he did not commit.

“A lot of people scream and holler that they’re innocent. But few people listen,” Gillispie said. “UC listens.”

Gillispie said he didn’t sleep for days after his release. Later he learned that’s not uncommon for recent exonerees.

“You think it’s a dream. You’re afraid you’ll wake up to the same nightmare of prison,” Gillispie said.

Ru-El Sailor, who was exonerated in March with help from UC's College of Law, also attended Thursday’s hearing. After serving 15 years for a murder he did not commit, Sailor said he has spent the past few months bonding with family and friends. This summer he plans to do some traveling – which seemed like an impossible dream just months ago.

"You’re working with a real person who needs help. It gives everyone a greater sense of purpose when you meet with exonerees and hear their stories and the trauma they went through."

‒ Rebecca Brizzolara, 2017 UC College of Law graduate who worked on Christopher Miller case

Family members hug Christopher Miller outside the Cuyahoga County Justice Center on Thursday after a judge ordered his 2002 convictions vacated.

Students form the 'backbone' of the OIP

The Ohio Innocence Project (OIP) at the University of Cincinnati College of Law — Ohio’s only law school-based innocence organization — is one of the most well-known and successful of its kind in the nation. Since its launch in 2003, the OIP has helped free 27 wrongfully convicted inmates who've collectively served nearly 500 years in prison.

Those successes, staff members say, wouldn't be possible without second-year UC law school students who work with the OIP year-round to overturn wrongful convictions and right injustice.

"Students are the backbone of what the OIP does," said Brian Howe, an assistant professor of clinical law at the OIP. "We've had close to 10,000 requests [from incarcerated inmates] since OIP opened its doors. We have four full-time attorneys. Without students, we could not adequately investigate even a small fraction of that."

About half of the law school's incoming class each year applies for one of 20 positions as an OIP fellow. The work, a one-year stint, is both challenging and time-consuming, says Howe. Fellows work 40 hours a week through the summer and 10 hours a week through the academic year. Under the supervision of attorneys, students work in pairs to dig through case files, interview witnesses and attorneys, piece together crime scenes and seek out the latest in forensic techniques, such as DNA testing, to apply to cases.

"There’s no way we could do justice to these cases without the students," said Howe. "They are doing the work of the OIP."

The OIP celebrated its latest exoneration Thursday when a judge vacated the conviction of Chris Miller. Meet three OIP fellows who worked on his case:

Rebecca Brizzolara

Attending law school was always on Rebecca Brizzolara's academic radar, but the Cincinnati native still wasn't sure which area of law she wanted to specialize in when she entered UC's College of Law in 2014. One thing she was certain of, however, was that the OIP was making a difference — and she wanted to be part of it.

"I knew I wanted to do something that mattered," said Brizzolara, who graduated in 2017 and now works as an attorney with a startup insurance company.

Like all OIP fellows, Brizzolara first underwent an intensive two-week classroom instruction that introduced students to complex forensic technology, such as DNA and bite mark identification, as well as how to spot so-called junk science. Students also reviewed OIP success stories and met some of the 27 exonerees the OIP has helped free since its launch in 2003.

"It makes it very real," Brizzolara said, of meeting with exonerees. "You’re working with a real person who needs help. It gives everyone a greater sense of purpose when you meet with exonerees and hear their stories and the trauma they went through."

Rebecca Brizzolara

Chris Miller's file was among 15-20 cases assigned to Brizzolara and her partner. They, along with attorney Brian Howe, were the first from the OIP to speak with Miller about his case. By the end of the conversation, Brizzolara said all three were convinced of his innocence.

"The story didn't add up," she explained. "The DNA didn't point to Chris. The facts pointed to his innocence."

Brizzolara and her partner tracked down Miller’s trial transcripts and police records and investigated alternate suspects. Even after her yearlong fellowship with the OIP ended in 2016, she continued to request case updates. Then, finally, came the news that every OIP fellow dreams of hearing: Their client would finally walk free.

"You feel like, for once, the work you've done is truly making a difference in someone's life, and that's not a feeling most of us get in our everyday jobs," said Brizzolara. "It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity."

Colleen Reilly

Colleen Reilly

After working with refugee populations during her junior year in college, Colleen Reilly felt moved to do more to help people in local communities. When she learned about the Ohio Innocence Project, the Cincinnati native knew UC's College of Law was the school for her.

That decision, it would turn out, not only gave her the chance to help some of Ohio's most vulnerable people, but also allowed her to completely change a man's life.

Reilly, a 2018 graduate who's now studying for the bar exam, started her work as an OIP fellow in 2016. The OIP learning curve, she says, was a short one: While staff attorneys oversee all cases and are available for coaching and guidance, students plunge into cases, she said.

Fellows quickly learn how the prison system works, how best to talk to witnesses and effective techniques for communicating with clients, said Reilly. She and her partner pored so closely over trial transcripts and other case documents that she jokes she still has them memorized.

"We jumped right in. It's exhilarating and exciting, but also a little nerve-wracking," she admitted.

"You're eager to do the best work you can because these people's lives depend on the work that you do."

Chris Miller's case was one of about 40 cases assigned to Reilly and her partner, but it quickly became the one Reilly felt especially passionate about due to the sheer injustice of his conviction.

"They say your second year of law school is your hardest, but when you're working with the Innocence Project, it’s well worth it," she said. "You knew that you were doing work that could potentially affect somebody's life, not just reviewing statutes and cases."

Reilly's accepted a position with a law firm in Sidney, Ohio, but says she plans to work with legal aid and refugees and immigrants in the future. One of the most meaningful lessons she took from her time with the OIP is a heightened awareness of wrongful convictions, which she says will make her a better attorney.

"You think, 'That would never happen to me,' but there are more people becoming exonerated who thought the same thing," said Reilly. "If I am aware of these problems, I am more conscious of being engaged in behaviors that lead to wrongful convictions."

Katie Lucas

Katie Lucas had long felt drawn to the field of law and felt confident the UC College of Law provided the best avenue to achieve that dream.

"It's well-priced and a good education. It has a good reputation, and it's closest to downtown of all the law schools in the area. I thought it was a good opportunity to be near such a big city," she said.

Then Lucas heard about the OIP at an open house for incoming students and knew she made the right choice.

"I thought it was one of the coolest organizations I'd ever heard of. You're doing something that you enjoy while helping someone who doesn't have anyone else to help their cause," said Lucas. "It's a good way to give back."

Lucas received that chance to give back the summer of 2015 when she began working as a fellow with the OIP. After a whirlwind two-week classroom instruction, she began to delve into cases, interview witnesses and compile evidence. The work was tedious, but worthwhile, she said.

Katie Lucas

"People can't remember what they did a month ago, let alone four years ago," she explained. "Sometimes there is really good evidence, other times it is harder to find. You have to go back and piece together a crime scene almost."

And not every case passes OIP's muster, Lucas points out. The OIP receives more than 500 inquiries a year from prisoners or family members looking for help. Ultimately, it represents only about 2 percent of individuals who ask for assistance.

"We reviewed cases to see if they have evidence that could help them. We also reviewed the evidence to see if they actually are guilty. Some are innocent. Some are not," she explained.

Lucas and her partner were the first fellows from OIP to meet with Chris Miller in prison. Instantly, she felt his case was one that deserved OIP's attention.

"His co-defendants changed their story. He didn't change his story. The prosecution offered him a plea deal of seven years. He said he was innocent," she explained. “The trial transcript was very fishy. We thought, 'Wow, this could be a good case.'”

Lucas graduated in 2017 and accepted a position with an insurance company in Omaha, but continued to keep tabs on Miller's case. While she said she was overjoyed by the news of his exoneration, she also called the announcement "bittersweet."

"I'm so happy he's being exonerated; it's a long time coming," she said. "But he shouldn't have been there. He's been behind bars for much of his adulthood. It's been so heartbreaking that (so much) has been taken from him."

UC College of Law professor Brian Howe, left, and his client, Christopher Miller, listen to the judge's ruling ordering Miller's immediate release Thursday in Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court.

Family members of Christopher Miller listen to proceedings Thursday in Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court.

Ohio Innocence Project exonerees Dean Gillispie, far left, and Ru-El Sailor congratulate Christopher Miller on Thursday on the steps of the Cuyahoga County Justice Center. Gillispie and Sailor were released from prison with help from students and faculty at UC's College of Law and its Ohio Innocence Project.

UC College of Law students pose outside the Cuyahoga County Justice Center on Thursday with some of the people they have helped exonerate as part of UC's Ohio Innocence Project.

Make a difference

Do you envision a future where you use your law degree to help others? Take the first step by exploring your options at the University of Cincinnati College of Law. You can also support the OIP financially with an online gift.