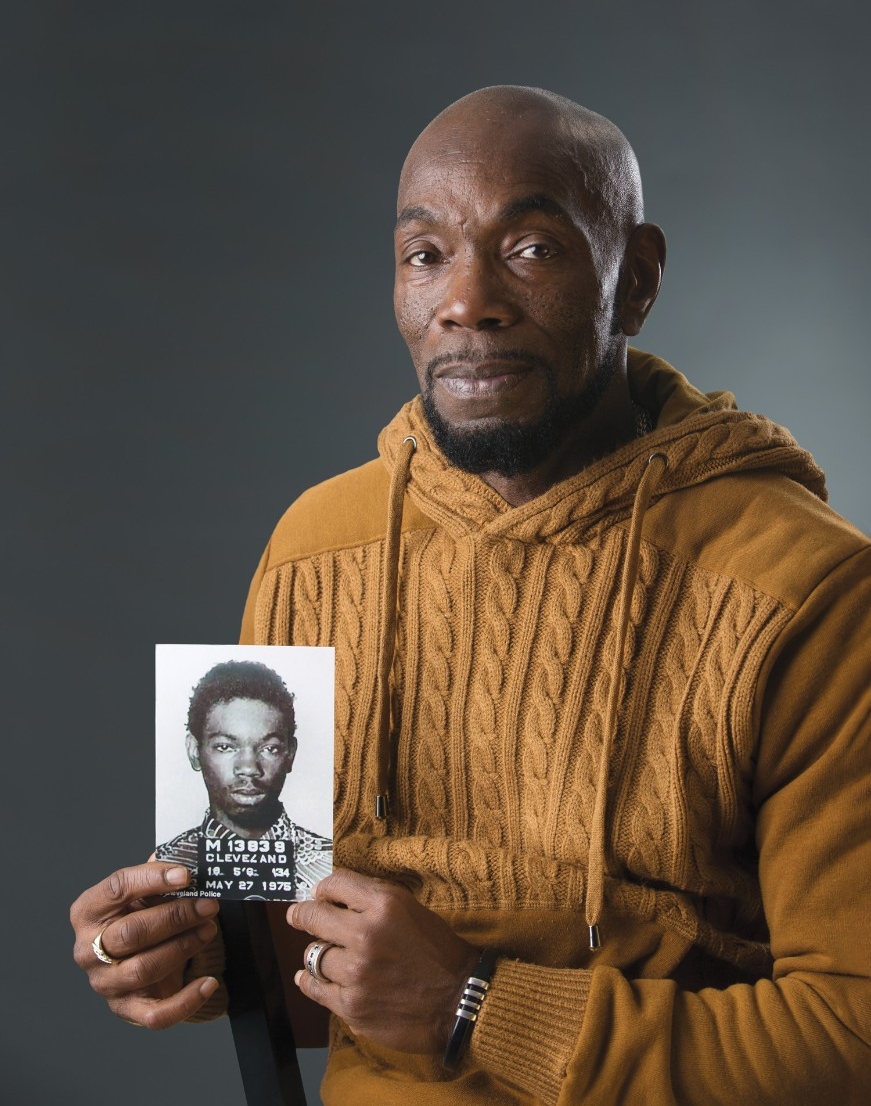

Exoneree Ricky Jackson reflects on the 39 years he spent in prison for a crime he did not commit. Photo/Lisa Ventre

A new book by a founder of the University of Cincinnati's Ohio Innocence Project sheds light on a criminal justice system that sends far too many innocent people to prison.

Ricky Jackson stood inside a church in Cleveland, Ohio, anxiously awaiting the chance to come face-to-face with his accuser — the man responsible for sending him to prison for 39 years.

Jackson was fresh out of jail, and tears of joy had barely dried following his 2014 exoneration for a 1975 murder conviction. The state’s key witness — Ed Vernon, just 12 years old at the time — testified that he saw Jackson with two others gun down a man outside a corner store. But after nearly four decades, Vernon recanted, explaining that police intimidated him into testifying, and all three innocent men were freed. Jackson became the longest-serving exoneree in U.S. history, and he was about to look into the eyes of the man who put him behind bars yet ultimately helped set him free.

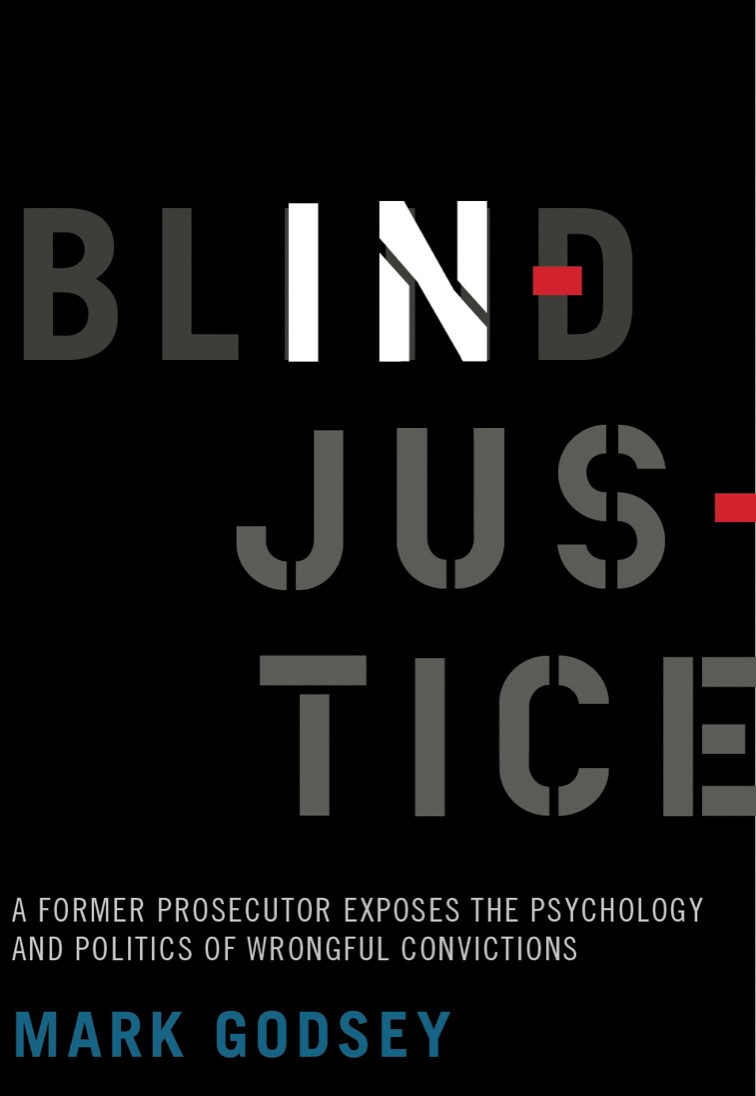

The scene inside Vernon’s church that day is described by UC College of Law Professor Mark Godsey in his upcoming book, “Blind Injustice.”

“When Vernon entered the chapel that day, Ricky walked up to him, hugged him, and whispered in his ear, ‘I forgive you. I want you to live a good life,’” writes Godsey. “Ricky then continued to hold him while Vernon sobbed in his arms. Ricky later told me that as Vernon sobbed, he became lighter in Ricky’s arms, and Vernon gradually began to stand more upright. A physical transformation occurred before Ricky’s eyes, as Vernon’s burden began to dissipate.”

The burden of knowing innocent men and women are sitting in prison is something Godsey has become all too familiar with over the last 14 years since starting at the Ohio Innocence Project (OIP) at UC in 2003.

To date, the OIP in UC’s Lois and Richard Rosenthal Institute for Justice has freed two dozen wrongfully convicted inmates from Ohio prisons who together had served more than 450 years for crimes they did not commit.

Featured in a 10-page Time magazine feature in February, the OIP has become one of the most active and successful innocence projects worldwide.

And along the way, Godsey — himself a former federal prosecutor — has had a front-row seat to the psychology and politics that lead to wrongful convictions.

After witnessing enough disturbing trends to fill a book, he sat down and wrote one. “Blind Injustice” is expected to hit shelves in September 2017.

When his book debuts, Godsey hopes readers will better understand why an increasing number of innocent people are walking out of prison after spending most of their lives locked up for crimes they didn’t do.

Ricky Jackson holds the 1975 mug shot police took of him when he was booked as a teenager. Photo/Lisa Ventre

“The discovery of hundreds if not thousands of wrongful convictions in the past 25 years should be viewed by the criminal justice system as indicative of a disaster,” writes Godsey. “A mass disaster.”

According to the National Registry of Exonerations, nearly 2,000 people have been set free for crimes they didn’t do since 1989. Still, Godsey says most of the American public remains in a “fog,” oblivious to how the system is stacked against defendants who don’t stand a chance if police, prosecutors or judges have what he refers to in his book as “tunnel vision,” a premature conclusion of guilt.

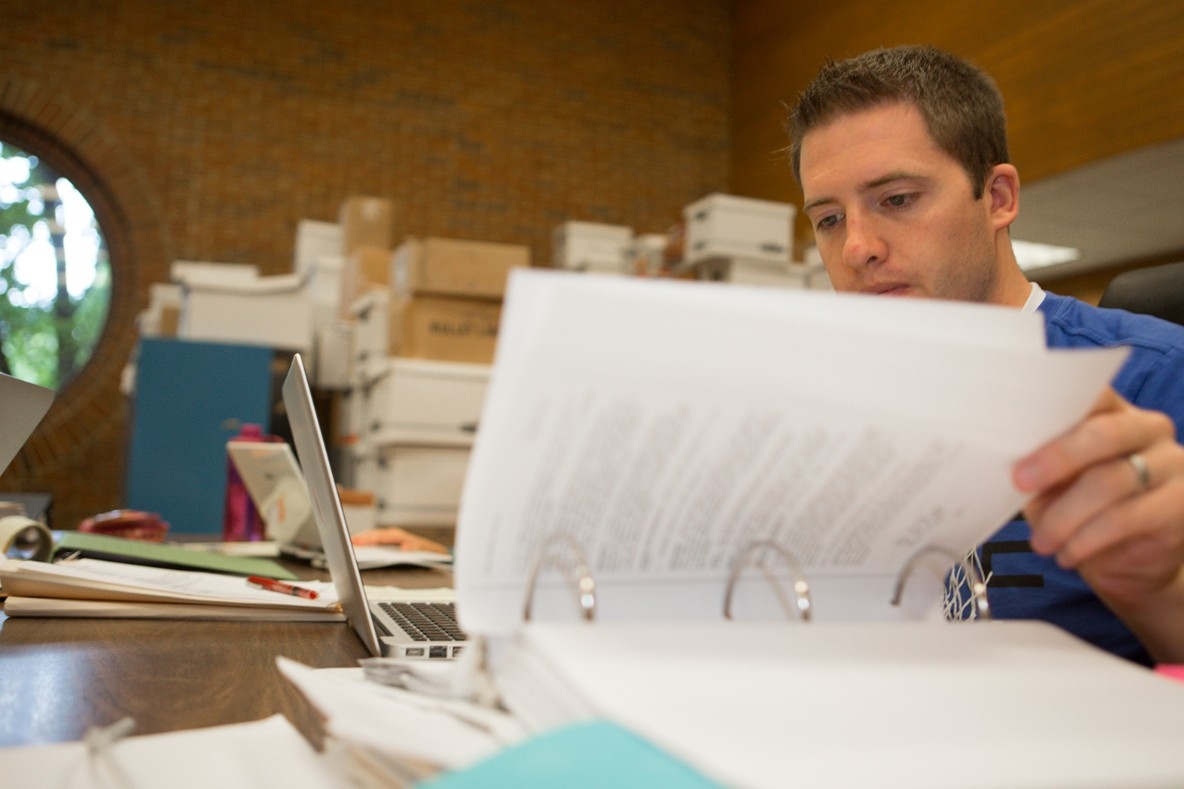

Mark Godsey discusses a case in the Ohio Innocence Project space at the UC College of Law. Photo/Lisa Ventre

In chapter after chapter, Godsey calls into question a criminal justice system that he says is rife with human error, from junk science forensics to simple human bias. As a former prosecutor, Godsey says he views his book as both a memoir and a confessional.

“I look back, and I see that I did things that I don’t agree with now,” he says. “I would love it if prosecutors and police officers read this book. It is not an attack on them. We take certain roles, and we lose our humanity in the process. I did that myself.”

Godsey says police and prosecutors are under great pressure to solve heinous crimes, and the politics, he says, all too often cloud the process and lead to mistakes or overreaches.

Even when a miscarriage of justice has been brought to light by OIP investigations, he says, officials in the system often remain in such denial that they purposely stand in the way of correcting mistakes.

“As an innocence lawyer and activist, I have routinely witnessed the unjust behavior of police, prosecutors and even judges and how this behavior has caused untold pain to thousands of innocent people suffering at the hands of the system,” Godsey writes.

Godsey’s eyes were first opened in 2001 after he joined the law faculty at Northern Kentucky University and filled in for a professor who oversaw the Kentucky Innocence Project. Students were reporting on an inmate in prison for rape whom they suspected was innocent.

“I sat there and listened to their description and internally rolled my eyes,” he writes in his book. “‘How naive,’ I thought. What a bunch of gullible, bleeding-heart law students.”

When the DNA test came back, however, the man was exonerated and released after 13 years in prison. “This was, needless to say, an eye-opening experience for me, the prosecutor’s prosecutor,” shares Godsey. “I was shocked.”

Mark Godsey's book is expected to be released in September 2017.

Soon after, he attended the national Innocence Network conference, and by the time he left, he saw everything in a brand new light. “There were problems in the system which I, as a prosecutor, should have seen, but I had simply been in denial.”

The next year, Godsey got a job at the UC College of Law and began directing the OIP, founded a year earlier by local lawyers, including John Cranley, currently mayor of Cincinnati.

Godsey’s group has helped free 23 men and one woman since those early days, and those cases represent only a sliver of the thousands they have examined.

The OIP — resembling a mini law firm in the UC college — is made up of students, a few staff attorneys and an administrative assistant. They receive more than 500 inquiries a year from prisoners or family members looking for help. Tall stacks of boxes indicate the volume of work.

Godsey compares their caseload to a massive conveyor belt with holes in it. “They are all moving along in the beginning, then some start falling through the holes,” he says.

Many inquiries get kicked early for obvious reasons: The inmate is not from Ohio, or they did the crime, but they disagree with the sentence. In hundreds of cases, inmates are sent a 23-page questionnaire. Some never return it, and even more cases melt away as OIP staff members dig into the details and discover claims of new evidence or a new witness that never pan out.

In other instances, OIP attorneys push for DNA testing only to confirm a client actually is the murderer or rapist the state said he was.

“In a lot of our cases, our investigation confirms they are guilty,” says Godsey. “I always tell our students that is the best answer you can hope for. If you are sitting around hoping that the system made a mistake and the true perpetrator has been out on the street committing more crimes, you are sick.”

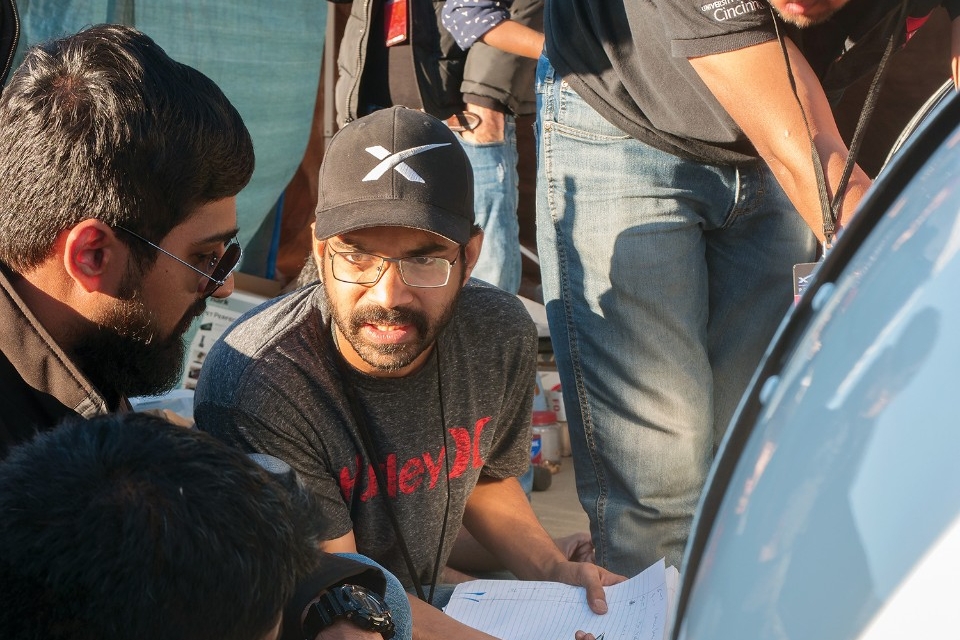

OIP students hard at work at the UC College of Law. Photos/Lisa Ventre

Ultimately the OIP ends up representing roughly 2 percent of individuals who ask for help. That’s about 10 out of every 500. Yet, despite the grind of sifting through cases that often go nowhere, it’s the wins that keep them motivated to press on, says OIP staff attorney and UC grad Jennifer Bergeron, JD ’02.

“Once you read the heartbreaking letters we receive, investigate a case and find evidence showing that someone is sitting in prison, often for life, for something they did not do, you can’t walk away,” she says. “It’s an incredible honor and burden to represent someone who the justice system has failed.”

Godsey points out that his students and staff are driven by social justice. “They are people who work for passion,” he says. “It is a tough job. These are true do-gooder type personalities who are willing to make less money, work longer hours and have a sometimes demoralizing and frustrating job because that is the only way they would have it.”

As he once wrote in an email to his team to lift their spirits after a tough loss, “… fighting for another human being who no one else will fight for has incredible value in and of itself. … the real courage is doing something because it’s right even if it has a high chance of ending in gut-wrenching injustice.”

The victories bring what Godsey calls the “Kodak moments,” when the media surfaces to get footage of an inmate taking his first careful steps out of prison — free for the first time in decades.

But Godsey prizes the more intimate moments, like when he was driving with his two young children in 2005 and his cellphone rang. The call was from the Ohio attorney general’s office, the top law official in the state of Ohio, to inform him that the state would stand alongside the OIP and support the case to get a man exonerated. That man, Clarence Elkins, had been in prison more than seven years.

Elkins had been given a life sentence for allegedly raping and murdering his mother-in-law and raping his 6-year-old niece, who told police the perpetrator looked like her Uncle Clarence. Though Elkins had an alibi and all the physical evidence pointed to his innocence, he was convicted. The OIP proved through DNA testing that Elkins was not the perpetrator and even positively matched the DNA to the true culprit, a convicted child rapist who had lived just two doors down from where the crime was committed. In an incredible twist, the real killer happened to be in jail for another crime and was in the same facility. Elkins was able to collect the man’s cigarette butt and mail it to the DNA lab.

Former Ohio Attorney General Jim Petro visited campus after the 2005 Clarence Elkins case. Elkins is listening in the background. Petro explained to UC law students why he took a stand with the OIP and against state prosecutors to exonerate Elkins. Photo/Dottie Stover

Opposed by the judge and the prosecutor at every turn, Godsey eventually turned to the state attorney general.

“When I got the call, I got emotional and had to pull over to the side of the road,” says Godsey. Soon after, he received copies of letters from the state office declaring their intentions to join the case. “I drove straight to prison to see Clarence and tell him the news. I held up the two pieces of paper on the glass during the prison visit. He read it. It was just a very emotional moment.”

The wins for UC’s OIP haven’t only involved escorting free men and women from lockup. The OIP was also behind Senate Bill 77, a piece of Ohio legislation passed in 2010 that set statewide standards for retaining biological evidence, taking DNA in felony arrests and establishing new procedures for police lineups. Godsey is also a leading figure in the international innocence scene and often travels to other countries to speak or help networks get off the ground.

Asked where the innocence movement is headed, Godsey says it should be viewed much like the civil rights movement.

“We are at the beginning of a many decades-long movement that’s going to transform the criminal justice system,” he says. “Because of advances in psychology and because of the innocence movement, we are realizing there are a lot of things we can do differently to make the system more accurate. This is going to win out because there is no debate on the merits. You are just fighting people whose minds are closed because it has been done this way for centuries.”

Like civil rights, he says, there won’t be a eureka moment where somebody stands up and convinces everybody.

“These battles are won by activists continuing to holler and scream,” he says. “This is going to take people working and educating and talking for decades and decades.”

Featured in Time

The Ohio Innocence Project has received an unprecedented honor – a feature in TIME magazine’s special edition examining wrongful convictions. The issue, which is anticipated to sell over a half a million copies, was recently published (Feb 2017) and is available at newsstands across the country.

“I’m thrilled that Time has dedicated an entire issue to the Innocence Movement, which demonstrates the enormous impact it has had on our criminal justice system,” says Godsey. “We at OIP are honored to have been highlighted as a central player in what is now becoming a global human rights movement. And we are thankful to the University of Cincinnati and our many donors for making it all possible.”

The issue, “Innocent: The Fight Against Wrongful Convictions,” takes a look at 25 years of the innocence movement. The Ohio Innocence Project (OIP) is highlighted with a multi-page spread.

Bearcats Dash & Bash

Second annual event is Sunday, Oct. 1

The second annual Bearcats Dash & Bash 18.19K and 5k races, co-sponsored by the UC Department of Athletics and the Ohio Innocence Project, is Sunday, Oct. 1, 2017, at UC. Last year’s event set a Cincinnati record for the first year of a race with more than 1,800 participants. All proceeds benefit the UC Athletics Scholarship Fund and the Ohio Innocence Project.

- Visit Bearcatsdash.com to register and learn more.

Record gift expands OIP’s future

A record $15 million bequest by philanthropist Dick Rosenthal will help assure that UC’s Ohio Innocence Project will continue well into the future. He and his late wife, Lois, first established the Lois and Richard Rosenthal Institute for Justice at UC in 2004, which includes the OIP. The latest gift is considered the largest to any innocence project in history.

Dick Rosenthal poses with Nancy Smith during the Dash & Bash event last year. Smith is the project’s lone female exoneree, freed in 2009 after spending 15 years in prison. Photo/Jay Yocis

Jackson with last year’s winner of the 18.19k, Josh Bokelman. Photo/Jay Yocis

Dash & Bash winner’s Facebook post

“In this picture you will find a man with remarkable endurance … and I’m also in it as well. They say records are meant to be broken, and in most all cases they’re right. I hope next year someone absolutely destroys mine. That being said, I hope Mr. Jackson’s record lasts forever, that his experience remains unparalleled, and the system can serve the future far better than it ever did him. When the photographer came up to take my picture Mr. Jackson stepped aside saying he didn’t belong in it, but after some coaxing he reluctantly stepped in. He didn’t want to steal any of my thunder, but little does he know that he is the thunder. For one hour and seven minutes last Sunday I put one foot in front of the other, which seems comical compared to his 39-year struggle to justice, truth and exoneration. Truth is, I’m really the one that doesn’t belong in this picture. I’m humbled by the fact he let me join him. Thanks, Ricky.”

— Josh Bokelman

John Bach

As editor of UC Magazine, John enjoys the opportunity to put a human face on a large institution by telling compelling stories of the University of Cincinnati's incredible community of alumni, faculty, staff and students.

John.Bach@uc.edu

FEATURES

UC law professor and co-founder of the Ohio Innocence Project reflects on 24 wrongly convicted individuals.

UC student team tests finalist prototype at Elon Musk’s worldwide Hyperloop competition.

ArtWorks and UC have enriched Cincinnati’s cultural landscape with public art for more than two decades.

How a former Bearcat overcame a brush with death, got drafted by the Reds and turned a school bus into a home.

UC doctor leads trial of marijuana-based prescription drug showing real promise for epilepsy patients.

Building a better Business School

UC breaks ground on a new $120 million home for the Carl H. Lindner College of Business.