by John Bach

Photos by Jay Yocis

University of Cincinnati sends team of scholars to Elon Musk’s doorstep in an international competition to redefine high-speed transportation.

A team of UC students is on the ground at SpaceX. Literally on the ground. Like bellies on blacktop.

It’s Saturday, Jan. 28, 2017, and the clock is ticking toward Sunday’s main event, a high-stakes competition to transform transportation that would draw thousands of onlookers and international media. UC is one of just 27 Hyperloop teams in a worldwide race to create a prototype pod that could one day hold passengers traveling in a tube at more than 700 mph.

The UC students, scattered around their prototype and peering up from a worm’s eye view, are transfixed on the fouled-up braking system that’s currently wrecking their world. Here in the parking lot of SpaceX — the absurdly ambitious rocket company in Hawthorne, California — the sounds of helicopters and small planes are ever-present as pilots buzz in and out of a nearby municipal airstrip, yet no one looks up, not even the aerospace students. There’s no time.

The pressure of the competition seems to be closing in from all sides as students search for answers as to why a controller for an actuator is malfunctioning. They must solve the issue, and fast, or risk derailing the project. The countless sleepless nights, the design work, the drawings, the streams of custom code, the months of fabrication and assembly. It all hangs in the balance, including one student’s dream, which started clear back in August 2015.

“This shows that if a society and a people are determined, you can do things like land on the moon...“

—Dhaval Shiyani

Back then, Dhaval Shiyani, team captain, was working the graveyard shift at Morgens Hall on campus when he stumbled upon Elon Musk’s original Hyperloop white paper online. By the end of the night (and 58 pages later), Shiyani, an India-born aerospace engineering grad student, was thoroughly enthralled and knew he had to get involved. He had fallen in love with the billionaire inventor’s concept, a solar-powered passenger system that would rocket pods loaded with people between distant cities in vacuum-sealed tubes.

Musk, the CEO of both Tesla and SpaceX, had challenged universities and independent amateur teams to develop prototypes for that system and would eventually invite them for public testing in a one-of-a-kind, mile-long “Hypertube” he had constructed near SpaceX.

Over the next 18 months, Shiyani assembled dozens of fellow UC students who began conceptualizing and ultimately building a prototype. To get to the competition, however, Hyperloop UC — the only team from the state of Ohio — first had to advance from more than 1,200 conceptual entries. Of those, 124 presented at a design weekend at Texas A&M in January 2016, and just 30 were invited to build and ship prototypes.

“It is sort of like an engineering Olympics,” says Shiyani. “We are competing against the rest of the world. But that is good. This kind of competition encourages innovation and fast-paced technology advances.”

He compares the Hyperloop competition to the space race of the 1960s.

“This shows that if a society and a people are determined, you can do things like land on the moon,” says Shiyani, whose team worked around the clock for weeks to finalize their entry. A week prior to the contest, he admitted to getting only about eight hours of sleep total in the previous three nights.

“I could lie down and sleep on this floor,” he said then, pointing to the concrete inside the high bay of Rhodes Hall at UC where they did assembly and testing. “Since it is toward the finish line, there is a lot of panic.”

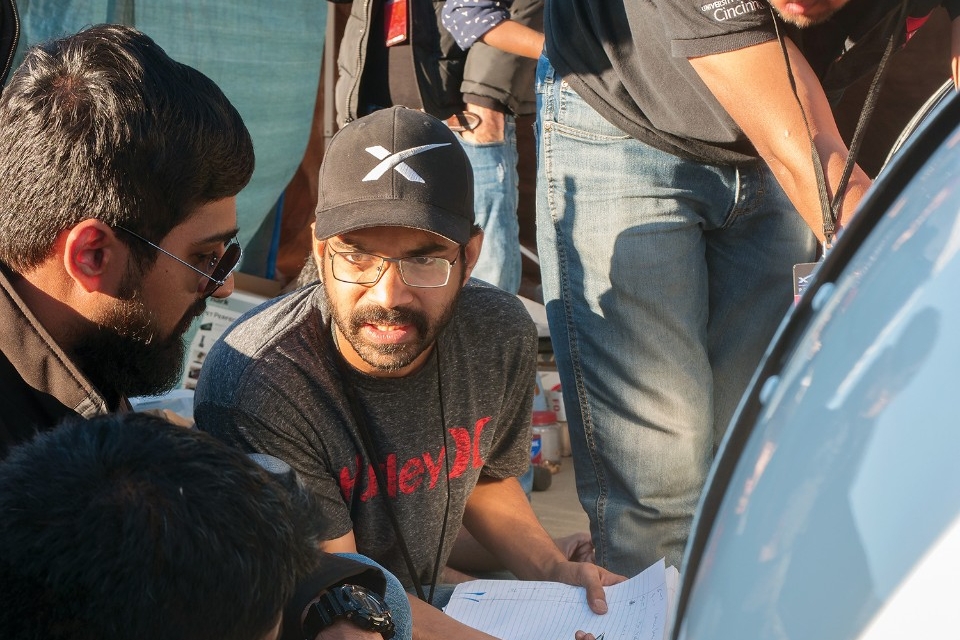

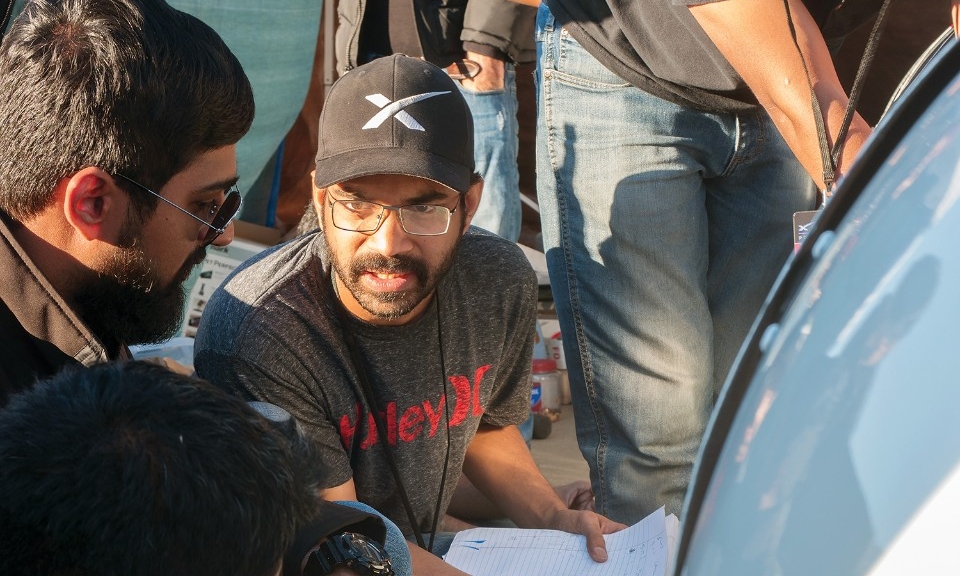

Hyperloop UC team members gather to discuss ideas during SpaceX competition.

The belly of their prototype contained most of the brains of the pod.

The team spent hours peering under their pod hoping for a breakthrough.

Dhaval Shiyani, right, finally got to meet his idol Elon Musk as he made his way through the crowd to view each team's prototype.

Ultimately, the students hope they can contribute to the technology they believe will shift high-speed transportation as we know it, an advance that would allow travel and shipping at roughly 200 mph faster than commercial airliners. The impact would effectively close the commuter gap and allow passengers to live 400 miles from work and still commute in under 40 minutes. Think Cincinnati to New York in under an hour, or Los Angeles to San Francisco in 30 minutes.

In addition to the SpaceX contest, private firms unassociated with SpaceX are also carrying Musk’s idea forward by building Hyperloop infrastructure in the United Arab Emirates, South Korea, the Czech Republic and other locations around the globe. Hyperloop One, a startup out of Los Angeles, demonstrated their proof of concept outside Las Vegas last summer. That firm claims they’ll deliver airline speeds at busline prices.

Ironically, as Hyperloop comes closer to fruition, society may have Los Angeles traffic to thank for the inspiration. Fed up with the daily snarl, Musk thought up the idea while sitting in gridlock. He first cast the vision in 2013 when SpaceX posted his white paper, complete with back-of-the-napkin type calculations. The big idea was to connect major cities with elevated vacuum tubes that would follow existing interstates and allow passenger pods to dart along on a cushion of air at more than 700 mph.

The concept sounds outrageous. Picture a pneumatic tube at a drive-thru bank on a grand scale. Or for cartoon lovers, it’s “The Jetsons” tubes in real life. Hyperloop would be both faster and more sustainable than either air travel or high-speed rail, yet, according to Musk, it is absolutely achievable. He even made a surprise speaking appearance during the Texas A&M design weekend last year to reinforce how serious he was about it.

“I’m starting to think this is really going to happen,” he told more than a thousand admiring engineers who were there as part of the competition. “It is clear that the public and the world wants something new.”

Musk loves the idea of being able to live in one city and work in another.

“This is a journey of discovery to see what is the right solution,” added Musk. “We really want this to be something that you could see as an evolutionary path to a real system, real Hyperloops that could be deployed around the world and used by millions of people.”

A year almost to the day later, 27 prototypes had become reality and were sitting outside Musk’s corporate front door in California for competition weekend. Leading up to the race, UC and teams from across the U.S. and as far away as Japan and the Netherlands were huddled around their pods working feverishly to meet a 97-point checklist that would include passing preliminary testing in a vacuum chamber and on a short open-air track. It was a brainiac’s dream, not to mention a seriously high concentration of nerds-per-acre.

All joking aside, however, the pressure was real. Only those teams that checked every box for the judges would get to move on to the final test in which pods would be loaded into the mile-long, 6-foot diameter depressurized steel Hypertube, then fired forward by a “pusher” that could reach 230 mph.

There in the lot on Saturday with the hours melting away in the Southern California sun, the 30 UC students who made the trip could see the Hypertube a block away, but considering the technical complications, it might as well have been back in Cincinnati.

“We are just trying to keep our cool and try to solve it,” says Siddharth Sridhar, the team’s director of control systems. “As of now [24 hours until the main event], this is the most challenging moment.”

He and several others from the engineering team had already pulled sensors and motor control boards from their pod and taken them back to their Airbnb 15 minutes away in Redondo Beach with hopes that an all-night tinkering session might help crack the problem. They worked to recalibrate the system, and then took turns ducking their heads into the pod’s exposed belly to reassemble everything while other team members exchanged nervous glances. “Stress has been high,” admits Vignesh Jayakumar, a PhD student from UC’s structures team, while sitting next to the pod. “It was all working fine until yesterday when it decided to give us trouble.”

A breakthrough, but too late

Before they left SpaceX on Saturday, UC’s team finally arrived at a fix and was able to put together a workaround. They would have to sacrifice some braking power and would need to ratchet down their top speed, but they were one step closer to actually getting into the pod race. The team even cleared testing in the “vac chamber,” which meant all components performed successfully in a low-pressure environment.

It was a major hurdle, but unfortunately, they received crushing news the next morning. With just two hours before the official race was to begin, SpaceX officials informed them and nearly two dozen other teams that they had simply run out of time to complete testing.

As it turned out, only three teams advanced through the gauntlet to get into the Hypertube. Those teams were from Delft University in the Netherlands, Technical University in Germany and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

“Everyone is disappointed right now,” says team captain Shiyani soon after getting the news. “There was a lot of hope, but I’m very sad and sorry. I’m still very proud of all we have accomplished. We have learned a lot, but this is a tough problem to solve.”

Shiyani, like any good researcher, says all they have learned and all the data they’ve gathered will inform UC’s next entry, since SpaceX will host another pod competition this summer.

“We tried our best, and we’ll keep going,” he says.

UC College of Engineering and Applied Science Dean Teik Lim, who attended the event, explained just how proud the university has been of the team.

“From day one, Hyperloop UC has embodied the college and the university’s spirit of innovation and entrepreneurship,” says Lim, who opened up his own research space for the team to work. “We’ve enjoyed taking this journey with them, watching them design, prototype, redesign and prototype again, until they successfully achieved their vision. It has been most exciting. They have all come together to show the world what UC can do. And what they can do is truly phenomenal.”

The main Hyperloop event on Sunday — reminiscent of a gigantic street fair, complete with a fleet of food trucks, a live band and more — stretched down Jack Northrop Avenue alongside the SpaceX Hypertube, where all the teams, including more than 800 participants, displayed their prototypes.

Highlighting the day were the first-ever low-pressure passes through the Hypertube as the crowd watched the live action on video screens. By nightfall, Delft took home the top award for best overall score, and the German team was awarded for top speed (94 km/h).

Hyperloop UC’s team members were upbeat on the final day of competition despite not qualifying to run their prototype through the Hypertube. The day still included plenty of lasting memories, and none more exciting than when Musk dropped by UC’s display tent to see their work.

For Shiyani, it was a full-circle moment. He had gotten hooked on Musk’s Hyperloop idea nearly two years ago. Then, after assembling the team who built UC’s prototype, he got to shake Musk’s hand and thank him for “igniting the fire that started all of this.”

Musk said during the event that the ultimate goal of his challenge was to get students thinking in new ways about transport technology and to “get them to innovate and think in a way that is not just a repeat of the past but to explore the boundaries of physics.”

It’s just the beginning of a brand new day of travel, and UC’s team promises to return this summer for the next competition to further define Hyperloop’s trajectory.

Want more?

We sent a team to cover Hyperloop UC’s adventure in January. Explore the coverage below.

John Bach

As editor of UC Magazine, John enjoys the opportunity to put a human face on a large institution by telling compelling stories of the University of Cincinnati's incredible community of alumni, faculty, staff and students.

John.Bach@uc.edu

FEATURES

UC law professor and co-founder of the Ohio Innocence Project reflects on 24 wrongly convicted individuals.

UC student team tests finalist prototype at Elon Musk’s worldwide Hyperloop competition.

ArtWorks and UC have enriched Cincinnati’s cultural landscape with public art for more than two decades.

How a former Bearcat overcame a brush with death, got drafted by the Reds and turned a school bus into a home.

UC doctor leads trial of marijuana-based prescription drug showing real promise for epilepsy patients.

Building a better Business School

UC breaks ground on a new $120 million home for the Carl H. Lindner College of Business.