by Melanie Titanic-Schefft

photos by David Lentz

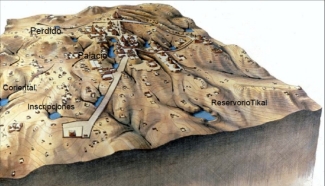

Droughts and climate change led to the eventual abandonment of Tikal, a major Mayan city of affluence that thrived for about 1,500 years in present-day Guatemala.

According to University of Cincinnati research just published in the prestigious Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences (PNAS), effective and sophisticated land-use practices sustained the thriving Mayan city of Tikal for more than 1,000 years until drought and climate change led to the abandonment of the city, which was once home to tens of thousands of people at its peak in A.D. 700.

Those are the findings of David Lentz, UC professor of biological sciences in the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences, and his colleagues. They analyzed surveys, satellite imagery, archaeological information, water, food and forest resources and pollen data at Tikal to establish the timeline and causes of its rise and subsequent demise of the prominent Mayan city. Their paper, “Forests, Fields and the Edge of Sustainability at the Ancient Maya City of Tikal,” is in the December issue of PNAS.

Faculty and student members of that research team are from UC, the University of Texas, Carnegie Mellon University, NASA, Brigham Young University and the Instituto de Antropologia e Historia and include: David Lentz, Nick Dunning, Vern Scarborough, Ken Tankersley, Silvia Alvarado, Walter Burgos, Sheryl Carcuz, Chris Carr, Mauricio Diaz, Rob Griffin, Angela Hood, Brian Lane, Raquel Macario, Blanca Mijangos, Kim Thompson, Eric Weaver, Thomas Sever, Liwy Grazioso, Carmen Ramos and Richard Terry.

Flourishing city clears way to its own demise

Archaeologists divide Mesoamerican development into three major time periods:

• PreClassic or Formative period extending from B.C. 1500 - A.D. 300

• Classic period extending from A.D. 300-950

• PostClassic period extending from A.D. 950-1521

Past Issues

Past Issues