by Deborah Rieselman, 4-13

In August 1934, a particular train ride from Chicago to Estes Park, Colo., was a trip of a lifetime. Among the passengers were all the East Coast delegates to a conference that would soon kick-start the national development of credit unions by founding a related trade association.

As the train wheels clattered over the tracks, delegates roamed the cars, getting to know each other, which unfortunately left them overlooking an apparent student in one of the cars. She seemed too inconsequential for anyone to notice, but the young woman was paying attention to them.

She particularly noted the conference leader's secretary was growing agitated at her inability to locate every delegate on the train. At one point, the exasperated woman groused that she had been unable to find delegate Louise McCarren even after searching every single train car and speaking to every person on the train — except "that college kid sitting over there."

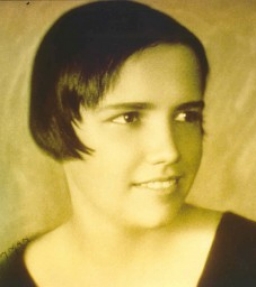

That "kid" was actually an attractive 24-year-old who had graduated with a business degree from the University of Cincinnati's College of Engineering and Commerce just two years earlier in 1932. She was on the trip at the encouragement of her employer, the Kroger Co., for which she worked in the corporate office. And, as everyone would soon discover, Louise was the youngest delegate attending the historic conference.

Having overheard the secretary's conversation, Louise announced that she was the missing delegate. That's when the secretary's boss, Roy Bergengren, rudely indicated she was too young and referred to her as “a mere girl.”

"I don't think I have ever seen a man so mad," she wrote in a letter years later. "He was insulted (that) the Kroger Company would send a young brat to such an important meeting."

But the Kroger Co. leadership apparently knew what it was doing. Louise ended up serving as secretary for the Estes Park conference, the delegates of which soon founded the Credit Union National Association (CUNA) and signed its constitution. Later, Louise would represent Ohio on the new CUNA board.

During the next 50 years, Louise McCarren Herring's commitment to credit unions steadily grew. Her achievements include the following:

- Founding the Ohio Credit Union League and working as its first managing director

- Serving as the state’s first credit-union supervisor

- Founding the National Deposit Guaranty Corp. and serving as its director

- Setting up 13 small credit unions for Kroger employees

- Personally organizing more than 500 credit unions all over Ohio

- Assisting Bergengren in organizing the Michigan and Kentucky credit-union leagues

Past Issues

Past Issues