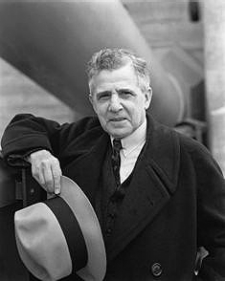

The man with the Golden Gate Bridge

The story of UC engineering alumnus Joseph Strauss

(This article was originally published by the University of Cincinnati Magazine in May 1987)

by Mark A. Davis

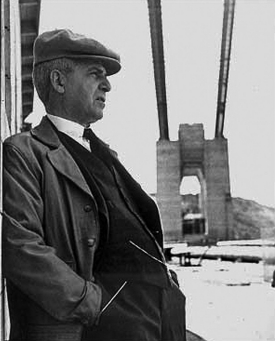

Not exactly a giant, Joseph Strauss was barely 5 feet tall. But then again, stature has nothing to do with the place he occupies in history books. Strauss was a giant in the engineering world. His greatest achievement: the Golden Gate Bridge.

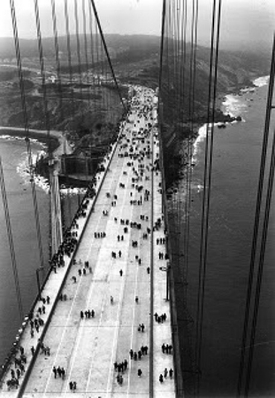

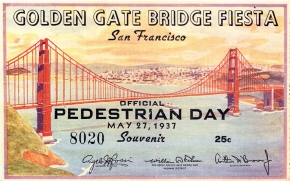

In 1937, the same year Amelia Earhart’s plane went down, the Golden Gate Bridge opened to the public. It was the pinnacle of a career that included the construction of more than 400 bridges worldwide, everywhere from downtown Chicago to the U.S.S.R.

That illustrious career began with his education at the University of Cincinnati. By all accounts, Strauss was both eager and driven. "He had great ambitions from the time he was a student," says Louis Laushey, dean emeritus of engineering.

That is something of an understatement. At the end of his senior year, 1892, with a degree in civil engineering, Strauss showed that he had dreams far beyond most of his peers.

Alfred Nippert, class of 1894, described Strauss's commencement night in “The Record” of Sigma Alpha Epsilon in 1937. Before a group of faculty, guests and speakers, Strauss delivered his senior thesis, a scheme for constructing a 50-mile-long bridge across the Bering Strait to connect Alaska and Russia. His professors were amused, but not surprised by the outlandish idea.

They had come to expect that from Joe. Despite his size, he had tried out for the football team his sophomore year. He lasted through the scrimmage, but spent post-game celebrations in the infirmary. He was instrumental in the establishment of a Sigma Alpha Epsilon chapter at UC. And in his senior year, he was the unlikely combination of class president, class poet and engineering honor student.

After graduation, Strauss worked at several different jobs, including one year as an instructor at UC, before accepting a position with the city of Chicago. It was there that Strauss made his reputation. The city was full of opportunities for a young bridge-builder, and Strauss was determined to make his mark. After butting heads with his superiors for several years over a new bridge he had designed, Strauss resigned from the city, opened his own business and revolutionized bridge-building. That company, Strauss Bascule Bridge Co., became the Strauss Engineering Corp., one of the leading consulting firms in the country.

Strauss's early successes eventually led him to California and his greatest achievement. A bridge over the Golden Gate, the entrance to San Francisco Bay from the Pacific Ocean, had been proposed and studied as early as 1918. The area was booming, and privately operated ferries were insufficient for the traffic demands. It took 10 years, dozens of lawsuits and finally state legislation before approval was given to form a committee to oversee the bridge effort in December 1928. That committee was organized in January 1929, and it named Strauss chief engineer the following October.

Strauss's appointment only marked the halfway point in the battle for the bridge. He had already testified countless times in court as an expert witness, and those trials were an uphill struggle. According to Strauss's book, “The Golden Gate Bridge,” "Reputable engineers stated under oath that the project would cost a total of $112,344,788 and that the piers and anchorages alone would cost $28,800,500." He adds, wryly, "These estimates, when compared with the Chief Engineer's [Strauss's] estimates and the actual cost as hereinafter mentioned, will be of special interest."

Later, Strauss was to put it more simply. “It took two decades and 200 million words to convince the people that the bridge was feasible, then only four years and $35 million to put the concrete and steel together.”

Strauss completed the project in 1937—on time, within the budget and without cutting any corners.

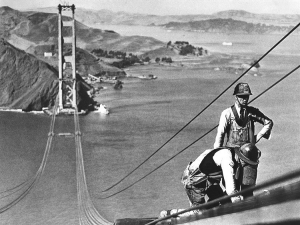

Yet there were complications—particularly with the foundation on the San Francisco side, said Constantine Papadakis, dean of the College of Engineering in ‘87. “Construction ran into tremendous problems with the depth of the water, the strong currents and storms on the bay. The task was not simple. It was quite an undertaking."

Dean Emeritus Laushey adds that Strauss made engineering history with his construction techniques. "At the time, this bridge had the longest span in the world," he says. "The depths they had to go with the rock for the pier was beyond anything ever done before, and techniques had to be developed to work in these hundreds of feet of water, under that water pressure and with a fair current."

"Strauss was a very careful individual, too," said Papadakis. "He set many new safety standards during the construction. He was careful in his planning."

A rule of thumb for bridge building in the 1930s was one fatality for every million dollars spent. That was not acceptable to Strauss.

He strung a net under the bridge's deck, something unheard of before. A fall from the bridge into the net initiated men into the Halfway to Hell Club, an organization that claimed 19 lucky members, men who might otherwise have died. Pete Williamson, one of the workers, was once quoted as saying, "Old Strauss enforced the rules. All a guy had to do was to stand out there on one foot, and he was fired."

Strauss nearly completed the bridge with a perfect safety record. Only a few months before opening, a derrick arm fell and killed a man. Several weeks later, some scaffolding collapsed, and 12 people fell into the net. As their co-workers looked on helplessly, the net ripped and dropped most of those men into the bay. Several clung to the bridge. Two men survived that accident. Still, with 11 fatalities, Strauss improved upon normal safety standards by better than 66 percent.

In those 45 years between graduation and construction of the Golden Gate Bridge, Strauss, who received an honorary doctorate from UC in 1930, kept his alma mater close to his heart . . . and close to his work. ”Strauss placed a brick from old McMicken Hall in one of the piers," Laushey explains. “He was so sentimental about UC he got that brick when they tore McMicken down, and he saved it to put in the bridge."

Dean Papadakis says he will search for the location of that brick when he and UC President Joseph Steger go to San Francisco to help the city celebrate the bridge's 50th anniversary. Papadakis says the brick is important because the connection it represents is more than just sentiment; it is an attitude that the College of Engineering has fostered for nearly 100 years.

"It is that free spirit, that broad, deep thinking that Strauss exhibited, which we see being repeated again and again through the history of the college," he says. "It is exciting to celebrate an anniversary like this and be able to think back at what a peer, a colleague and an alumnus succeeded in doing with the tools that were provided to him at UC."

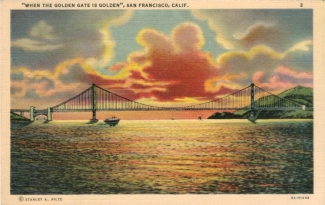

But it would be wrong to think Strauss's was merely a utilitarian talent. Just as he did in his senior year, Strauss combined the elements of engineer and poet in the Golden Gate Bridge.

"It is a sculpture of great prominence and sentimental value," Laushey explains. "Everybody coming into the harbor at San Francisco goes under the bridge.

“To people such as Chinese and Japanese immigrants and servicemen returning from war overseas, it is the first thing you see of the good old United States of America. It's an American monument, similar to the Statue of Liberty." Laushey knows. He was one of those servicemen who saw the Golden Gate Bridge when he returned from World War II.

.

And it would seem that Strauss himself had an idea of what the bridge would become. Once again, acting in his dual role of poet/engineer, he composed a poem, “At last the mighty task is done," for this marvel he had created. The last stanza reads:

High overhead its lights shall gleam,

Far, far below life's restless stream

Unceasingly shall flow;

For thus was spun its lithe fine form.

To fear not war, nor time, nor storm,

For Fate had meant it so.

Past Issues

Past Issues