UC president's 'brave' memoir explores his difficult past

Choked with tears, the woman's voice on the phone insisted that she had to talk to the dean. She was neither a student nor a parent, but a total stranger who had read the memoirs of Gregory Williams and believed that he was the one person to whom she could unburden her soul.

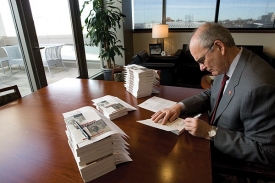

In 1995, such calls were not uncommon, much to the dismay of the dean's secretary, says Williams, UC's new president, but then Ohio State University's law dean. Reception to Williams' book, "Life on the Color Line: The True Story of a White Boy who Discovered He Was Black," was phenomenal, especially after the L.A. Times named it Book of the Year and Williams was featured on the "Oprah Winfrey Show," "ABC Nightline" with Ted Koppel and "NBC Dateline" with Tom Brokaw.

Initially, he was surprised how people flocked to his book signings, carrying photo albums and anxious to reveal stark family secrets, even while a long line of people stood behind them. "They feel comfortable telling me their story because I've divulged so much of my life in the book," he explains. "It's a deep and personal way to connect with people."

Nearly 15 years later, readers continue to reach out to him. "The average shelf life of a book is about six weeks," he says, "but I still receive long handwritten letters from people. A lot of interest is still out there."

One of the reasons for the enduring interest is that his story connects with readers on so many different levels. "The book is not just about race," he says. "It's about alcoholism, families, overcoming obstacles, dealing with poverty, being a teenager, all of those things."

Basically, it is the story of two privileged white brothers who overnight became oppressed black children wondering why their white relatives had abandoned them. That story sets the stage for a man who spent 20 years working full time while going to school full time to earn a bachelor's degree, two master's, a JD and a PhD. Next, he entered academics, working his way up from a professor, to a dean, then to president of City College of New York before becoming UC's president on Nov. 1, 2009.

Challenging childhood memories: Williams tells the whole story

As told by Gregory Williams

University of Cincinnati president

Often I am asked how a mixed-race boy growing up in abject poverty, shunned by both blacks and whites, could earn five college degrees and become a university president. This is my story.

Until I was 9, I lived a comfortable life as the son of reasonably wealthy "white" Virginia restaurant owners, Mary and James "Buster" Williams. Buster was gregarious, charming, volatile, laughing one minute, scary the next. My mother was remote.

The late '40s and early '50s were good times for those of us in America with enough money and the "right" skin color. I attended whites-only schools, whites-only skating rinks, whites-only theaters. Dad was said to have the Midas touch, and his business holdings seemed to expand daily.

I knew about poverty, of course, and I knew about segregation -- separate schools, not as bright and new as mine, and separate swimming pools, not freshly painted each summer like mine. Even our father's Open House Café had two serving areas. Black folks, who often didn't have the price of a meal, came to the back door.

But to me, the world was simple. Our world gave us what we needed, and we thought it should.

The darker moments in my early life were personal, not racial, but slowly became more frequent as my father's drinking exploded into full-blown alcoholism, followed by emotional and physical abuse. Our fragile family disintegrated, almost overnight.

My mother fled with my youngest brother and my sister when I was 10. Mike, my other younger brother, and I were left with ringside seats to watch our father's descent into the oblivion of alcoholism.

Day by day, we saw our material possessions disappear -- the restaurant, the tavern, the townhouse, the cars. Then we lost our dignity.

Every morning, Mike and I stood beside the highway waiting for our school bus, while Dad begged strangers for two quarters so we could buy a hot school lunch, often our only meal of the day. As we clutched those quarters, we felt both shame and relief.

With no life left for us in Virginia, the three of us boarded a Greyhound bus bound for Muncie, Ind., in January 1954 -- with all of our worldly possessions crammed into one canvas bag. My brother and I assumed we were off to visit my mother's parents, our white middle-class grandparents with whom we had spent many fun-filled summers and happy Christmases.

But after a long night of riding on that bus, my life changed forever. Somewhere in the middle of Ohio, my father leaned across the aisle and asked, "Greg, do you remember Miss Sallie?"

She was a tall, thin black woman who floated in and out of our lives. Cook. Maid. Not a person of consequence. My brother and I thought she was kind of mean, to tell the truth.

Then my father leaned closer and whispered, "She's my momma and your grandmother!"

I was shocked. This was impossible. All of us are white, I said to myself.

I took a closer look at my father, who at different times had passed for both Greek and Italian. I had to admit he didn't look exactly white. Goosebumps covered my arms as I realized that whatever he was, I was.

Even at 10, I knew I did not want to be black. My dad knew that, too.

He told us, in the vernacular of the time, "Life is going to be different from now on. In Virginia, you were white boys. In Indiana, you are going to be colored boys.

"People in Indiana will treat you differently. And you are just going to have to learn how to live with that."

I could not have imagined how true his words were. In the '30s and '40s, Indiana was the national headquarters of the Ku Klux Klan. And there were daily reminders when we stepped off that bus and walked down the railroad tracks to a part of town I had never seen before.

We were nowhere near the Muncie I knew -- the Muncie of Grandma and Grandpa Cook's lovely two-story house and lawn. I didn't know then that I would never again be welcome at their home and that my grandparents would never visit me.

After trudging along the tracks for about half a mile, we came to a weathered brown clapboard house oddly facing the railroad tracks rather than a street. An ugly 10-by-15-foot shed, completely covered from top to bottom with rough green spackled tarpaper, stood freakishly in the corner of the yard. It puzzled me that anyone would tarpaper a storage shed.

Empty beer bottles and trash littered the shed's porch where Dad rapped on the door. No answer. I braced myself, praying this was not our new home.

"Mom must be at work," he said. It was indeed my new "home," a two-room tarpaper shack with no sink, tub or shower.

Mike and I would soon be sleeping, or trying to sleep, on a single Army cot -- him curled up at one end and me at the other -- in the backroom that held the toilet. In the next room, Dad, his mother and various neighborhood "characters" would drink, gamble, fight and pass out nightly.

Soon I faced one of the hardest choices of my life: to dream or to despair. Too young to realize the odds against any one of us ever walking away from those railroad tracks and changing the circumstances of our lives, I chose to dream.

During that cold winter of 1954, only one person in all of Muncie chose to reach down to two lost little boys, Miss Dora Weekly Terry. The 55-year-old black woman with only an eighth-grade education brought us hot food after working a 10-hour day, six days a week, as a maid for a white family -- a job she did for the princely sum of $25 a week.

I relished those evenings when she shared a few leftovers from her employer's table. But as much as I welcomed the food, her acts of kindness nourished me immeasurably more.

By that summer, she had taken us into her own home and made us her boys. Although Miss Dora had virtually nothing, she gave us everything she had -- a home and her everlasting love. "Your Truly Mother" is how she signed her letters to me after I left for college, and it reflects how I feel about her to this day.

Of course, all the strength I gained from Miss Dora could not shield me from the larger world. I faced discrimination, violence, frustration and poverty.

Following the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregated schools, I saw on television a white-robed Klansman in front of a burning cross, railing against black and white children learning together. He claimed "race-mixing" would lead to the "bestial mongrel mulatto, the dreg of human society."

His nasal repetition of "mongrel mulatto" finally hit me like a thunderbolt. He was talking about me.

I was the Klan's worst nightmare. I was what the violence directed against integration was all about. I was what they hated and wanted to destroy. And that was the biggest puzzle in the world to me because I had absolutely nothing.

Every day, I had doubts and fears. I often wondered how I could survive. At school, my records were marked "C" for colored, and I was discouraged from the academic fast track. One year, I was denied the top academic prize that I earned because it was for whites only.

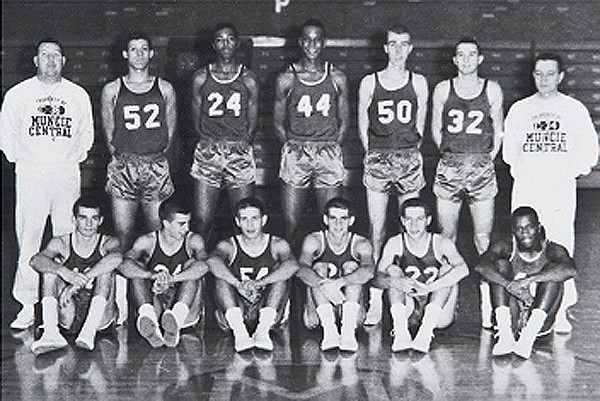

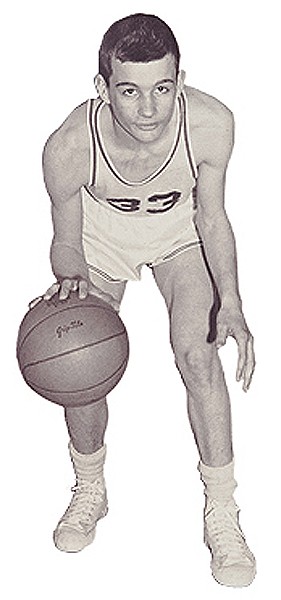

Still, in a city and state where accomplishment on the basketball court was the very definition of success, I felt the tantalizing possibility that skill could still trump race. Basketball was my passion, and at 6-2, I was pretty good on the court, as well as on the football field. When the team traveled, however, my black teammates and I were subjected to racist insults as we walked into fieldhouses and stepped onto the basketball courts.

Then there were girls. Fraught as the whole subject of the opposite sex is for any teenage boy, for me it was a minefield. Muncie would neither permit me to date white girls nor tolerate the sight of me with black girls. My very existence made people uncomfortable and shattered too many racial taboos.

This was the prevailing attitude in high school where I met the love of my life. In the spring semester of my senior year, I was given a study hall, probably to punish my insistence on a college-preparatory math class. I was assigned a seat behind a tall, dazzling blonde with blue-green eyes and a creamy complexion.

Sara Whitney had been an eighth-grade cheerleader when I played on the ninth-grade basketball team. Now she was a junior, and I was bowled over by her beauty. I was also immediately self-conscious about my threadbare clothes.

Unfortunately, the racism of the times made the development of a relationship very difficult, to say the least, but I will spare you the suspense and tell you that she has been my wife and best friend for more than 40 years.

After high school, I went to Ball State University at night with the dream of becoming a lawyer. I had to work full time as a deputy sheriff to support myself. The book ends there, but the story doesn't.

I had hoped and believed that telling my story would be useful to others. While I had an instinctive feeling that it would be painful to me, I did not know it would take me on a journey of 10 years to write. I couldn't have known how much it would give back to me, how it would make me value the people and places of my past, and how much I would grow from the response of my readers.

I have been asked to speak about the book to many audiences, in person and on camera. I have received thousands of letters from readers around the world who have been moved by the book. I have felt enormously strengthened by people from all walks of life and all colors who shared their stories with me.

I began "Life on the Color Line" in 1985 when I was 40 years old, the same age Dad was when he hit bottom. Although he lived for another 20 years, he never really surfaced again. And it wasn't until I was 40 that I felt strong enough to tell this story.

"I often think about life in Muncie," I write in the concluding chapter of the book.

"Sometimes in the middle of the night, halfway between sleep and consciousness, I go to the place where that bewildered boy of long ago still dwells in me, and my eyes fill with tears.

"We share the disbelief that all the things that happened to him in those early years of his life could have occurred. We cry together, and I tell him he is now in a safe place … and that a wiser and stronger friend is here to protect him.

"He wishes me well, but in his little manly way asks why it had to happen to him. Was there some deeper reason for the turn of events of his life, or was he just the victim of circumstance?

"I do believe that there is a reason that I was called upon to live the life that I was given … maybe to share it with others in the hope that no child will have to experience what I did. In spite of all the pain and grief of my early years, I am grateful to have been able to view the world from a place few men or women have stood. … I realize now that I am bound to live out my life in the middle of our society and hope that I can be a bridge between races, shouldering the heavy burden that almost destroyed my youth."

In 1995, President Williams' book, "Life on the Color Line: The True Story of a White Boy who Discovered He Was Black," was not only named L.A. Times Book of the Year, but Readers Digest ran a condensed version in its book "Today's Best Nonfiction." The book was originally published by Dutton, then Penguin published the paperback. After being asked by hundreds of people to write another book, Williams has begun one, but admits that his job doesn't leave him a lot of time to complete it.

Related stories:

Writing memoir was life-changing

Campus reviewers call book 'hopeful'

Links:

More articles and videos about UC President Gregory Williams

View President Williams' CV

Issue Archive

Issue Archive