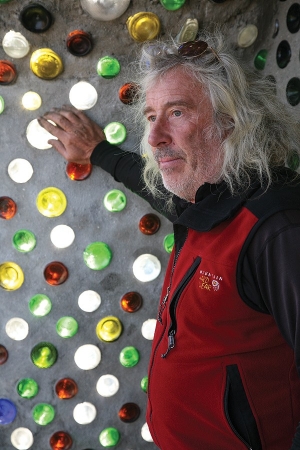

Rebel recycler, architect

He calls them "earthships."

Eco-architect Mike Reynolds is well known today for his off-the-power-grid houses made entirely from garbage -- tires, cans and plastic bottles packed with dirt. But the self-described "biotect" admits that along the way toward developing a sustainable home fashioned from landfill-destined materials, it was actually his career that nearly landed in the trash heap.

The first time Reynolds decided to ditch his profession was in the late '60s during a prestigious co-op position at a London architecture firm, where he found the work to be "super boring." "There was nothing inspirational about it," he says. "So after two weeks, I quit, bought a motorcycle, put my life on my back and headed for Africa."

Reynolds earned his way back into school by journaling across Europe, but by the time he graduated, he had become disillusioned withMikeReynolds1.tif his career path again. This time with what he believed to be an intense focus on turning profit over passion.

Choosing his own route once more, he headed to New Mexico to race motocross. It was there, in the early '70s, that he had a vision.

A newscast about the potential pollution problems from discarded beer and soda cans caught his attention. Other media reports of the long-term environmental effects of clear-cutting timber for building homes and a resulting lumber shortage also got him thinking. Soon, he connected the two issues and devised a solution: He would build a beer-can house.

"I was fresh out of architectural school and trying to figure out a way to build without wood," Reynolds says. "Those programs led me to try using the cans that were being thrown away."

He would spend the next 30-plus years improving his sustainable housing model. Today, the buildings provide thermal heat, cooling, water and electricity for residents, and even allow them to grow some of their own food. All energy is generated by the sun and wind, and sewage is treated on site and reused to grow plants. Total utility cost a year: less than $100.

"I see this as making a path to a different method of living that vastly reduces the stress on people and the planet," Reynolds says.

The radical method has received both praise and criticism through the years, depending on political, economic and social climates. In the '90s, Reynolds had to temporarily relinquish his architecture license amidst pressure from the State Architects Board of New Mexico due to the experimental nature of his homes.

"The whole thing was so unorthodox. Now it's being accepted, and with global warming, everyone is embracing it. But when I first started building, it was just too radical. "Now I'm getting praise for the work I was getting crucified for. I was just doing it too early, I guess."

Though the best examples of Reynolds' "biotecture" exist in three self-sustaining earthship communities in Taos, N.M., the structures can be found throughout the world, including Bolivia, France and India. Their popularity is due in part to Reynolds' other philosophy, which is to "put housing back into the hands of the people."

He created books with instructions simple enough for future owners to build their own homes. "That caught on and became a success. A lot of people have built their own earthships. I have learned that some people can't and shouldn't, but others can. It's all aimed at becoming very involved in your own home."

Also spreading earthships across continents are the humanitarian efforts by Reynolds and his team. Following the 2004 earthquake and tsunami that rocked India's Andaman Islands, the UC grad took out a loan and responded to an e-mail request he received asking for his help in providing shelter, water and sanitation for victims. His team replaced leaky, inferno-like tin shacks with a sustainable building created with plastic-bottle bricks that harvested clean water for the community. Tires packed with dirt helped make the structure more earthquake-proof.

Since then, Reynolds and his Earthship Biotecture team have taken on similar projects in Honduras after Hurricane Mitch and Mexico following Hurricane Rita. He's currently trying to obtain funding for another community project in Argentina and to build sustainable buildings for a number of school orphanages in Africa, including Sierra Leone.

"We do these projects for many reasons, but we always learn from doing them," Reynolds says. "It's good, but also … the team of us who went to the Andaman Islands, for instance, we'll never be the same after what we saw there. It just changes your whole reality."

Charitable work is just one part of Reynolds' mission to spread his alternative homes and lifestyle throughout the world. He will speak at the United Nations in June about how sustainable housing can help solve the current global economic crisis by teaching people to provide for themselves, even in the tough times.

"Take care of the people first, and let that evolve into a different kind of economy," Reynolds says. "We're talking about blazing a different trail for how to live on this planet, and yes, it goes way beyond architecture."

Link:

Issue Archive

Issue Archive