Clarice Reid, MD '59

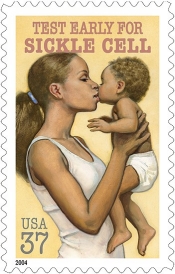

Clarice Reid was Cincinnati's only African-American pediatrician in private practice from 1962-68, then spent more than 20 years as coordinator of the National Sickle Cell Disease Program at the National Institutes of Health. Under her leadership, important advances in sickle-cell-disease research and hematology were made, transforming the management and care of patients and directly impacting the quality of their lives.

Raised in Birmingham, Ala., she attended a three-room elementary school and the city's only high school for black students. She went on to become the third African-American to graduate from the University of Cincinnati's College of Medicine.

Most educated "Negroes" could only be employed as postal workers or Pullman porters on the train. But it was understood in my family that we could and would obtain a college education and beyond.

Knowledge was power that no one could take away. That was the whole thing in my house.

There were no circumstances that we considered barriers to education other than traveling across town and bypassing other more convenient high schools, which we could not attend. This was a period in African-American history in the South where students were highly motivated to excel, and our families viewed education really as the "ultimate equalizer."

I inherited good genes in an educated household in Birmingham. I'm the youngest of three. My father was a teacher and a graduate of Talladega College. My grandmother was also a teacher with a degree from Alabama State. It seemed that she began our schooling when we started to walk. We had reading and math sessions every day. So we started out early with a sense of the importance of education and achievement.

I was very fortunate and blessed. Growing up in a segregated city brought people of color together in a common bond to do many things of interest. Several summers, my brothers and I traveled by train to visit family members in Chicago and went to the planetarium and museums.

"You can't do this; you can't get into that." You find out that those supposed roadblocks are not insurmountable challenges. Everybody told me it would be difficult to transfer to UC from Meharry Medical College in Nashville where I started medical school two years earlier, but it was not a problem at all. My husband, Arthur, was in Cincinnati, and he wanted to stop traveling back and forth from Cincinnati to Nashville.

Pediatrics was a perfect specialty for me as I was very attracted to children and saw this as an opportunity to positively influence their development. At the time of choosing a specialty, I was also a mother.

My husband had a law office upstairs, and I had the downstairs pediatric office. He'd come down, and I'd tell him, "I saw X number of patients today," and he'd say, "Well, how much money did you make?" I didn't know that I was supposed to make a living; it was all about taking care of children. He began charging me rent.

Take life as it comes. When I left Cincinnati to follow my husband to Washington, I had no idea what I would be doing professionally. All I could do was talk about how I didn't want to leave my job at Jewish Hospital as director of pediatrics and lose my identity. But as I moved on, I found identity in challenging new jobs that I never imagined. And later, when my husband said, "We're going back to Cincinnati," I said, "We're going where?"

I felt I had a responsibility to open the door for other minorities and women coming in while I was at the National Institutes of Health. I don't think it's enough for us, regardless of color or gender, to achieve and not look back and try to bring others along with us. You always need to say, "Did I allow other people to traverse this course and participate in the opportunities that were provided for me?"

If I'm feeling down, I just kind of toss it aside and think of all of the wonderful things that have happened in my life. My overall attitude is very positive, and I rarely feel down, but when my husband died in 2001, that was an emotionally low period in my life. I feel blessed by my four adult children, who are active in my life and didn't allow me to have long times where I could get depressed.

Doors open when you least expect it, but you need to be ready for those doors to open. I tell my children this all the time. It's not luck; it's where opportunity meets preparation.

My final career focus in the government was just such an example. When we came to the D.C. area, I had planned to continue working in the health-care delivery area. My plans would have required my working at a distance out of the Bethesda area, which was unacceptable with four children and the need to be involved in their daily lives. Friends directed me to the federal agencies, and this allowed me to use my clinical experience at a policy-making level and to work in the program area of sickle cell disease. This was a pathway that I had not planned but one that changed the course of my career.

My greatest accomplishment professionally was the opportunity to oversee the national sickle cell disease program of research and service for a period of over 20 years. This totally transformed the management and care of patients and impacted directly on the quality of lives of patients with sickle cell disease.

In 1969, Reid became director of pediatric education at Jewish Hospital, then chairwoman of the pediatrics department. In 1970, her family relocated to the Washington, D.C., area, and in '98, she retired as director of the NIH Division of Blood Diseases and Resources, part of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, for which she received the Superior Service Award, the U.S. Public Health Service's highest honor, and the Presidential Meritorious Executive Rank Award, recognizing outstanding achievements of senior executives in the federal government.

Her extensive career involved primary patient care, medical education and research administration. She continues to reside in Bethesda, Md., where she remains active in community and professional activities and travels extensively playing tournament duplicate bridge.

Issue Archive

Issue Archive