Cincinnati philanthropist Mary Emery funded construction at that site with the stipulation the auditorium would be available to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra. The Emery Auditorium remained the CSO's home for the next 24 years.

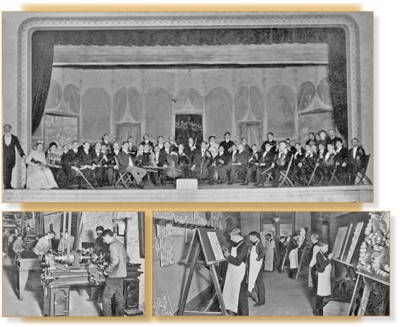

Still, residents came to OMI for more than the CSO and free lectures. By the early 20th century, the school had a full curriculum in architecture, chemistry, household art and science, industrial art, lithography, mechanics and electricity for nearly 1,500 evening and day students.

About the same time, OMI opened the city's first full-time technical high school, introduced continuing education for the city's public school teachers, housed a Student Symphony Orchestra of 50 musicians, opened an industrial museum and welcomed the community to its rooftop for parties on warm evenings. With a wonderful view, the parties were conducted next to OMI's vast greenhouses where staff raised homegrown vegetables to feed students and faculty during the day.

"Mary Emery insisted on the greenhouses, a holistic approach," archivist Maria Kreppel says with a smile. "All the activities were part of a vibrant building in a vibrant community, offering education, art and opportunities for social gatherings. There was a seamless connection between what went on in the building and what went on in the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood."

As society changed, the school responded. "World War I brought a U.S. Army contract to provide technical instruction to more than 1,000 injured servicemen," Kreppel says. "After the war, a new two-year work/study program in power laundry attracted students from 17 states, plus Canada, England, and Scotland -- testimony to OMI's growing reputation for leadership in applied learning."

In 1969, the institute, which had changed its name to the Ohio College of Applied Science by then, joined the University of Cincinnati. It moved from its Walnut Street location to the former Edgecliff College campus on Victory Parkway in 1989.

Between then and 2010, UC students took CAS courses at both the Victory Parkway and main campuses, with baccalaureate degrees in information technology augment traditional programs in architectural, chemical, construction, electrical and mechanical technologies. The newest program additions were later in horticulture and culinary science.

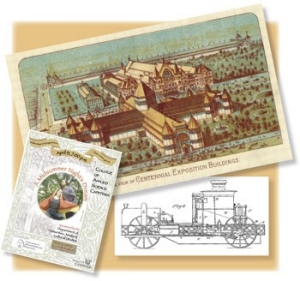

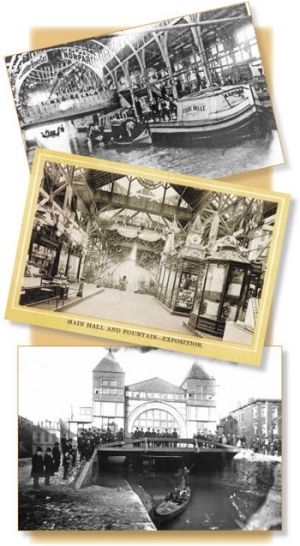

And as for community ties, every spring the college hosted a free, public performance of the Cincinnati Shakespeare Festival. In addition, senior students exhibited their first professional designs at a Tech Expo each May. In 2004, the expo was moved to the Cincinnati Convention Center in an effort to develop industry partnerships, welcome the public and open up the possibility of recreating some of the grandeur of the historic expositions, Kreppel says.

Perhaps most exciting was the way students continually searched for answers to complications in the home or workplace. Many of their inventions made it to market, while others simply provided a new way of looking at things, whether they are "greener" building designs, IT networks for community services or adaptive equipment for special-needs users.

In 2010, the College of Applied Science merged with the College of Engineering to create the College of Engineering and Applied Science. Students, faculty and personnel from the Victory Parkway campus moved to the main campus.

LINKS

Past Issues

Past Issues