by John Bach

Photographs by Andrew Higley

September 2004

September 2004

Insider's Tour of UC

Browse our archive of UC Magazine past issues.

Photographs by Andrew Higley

The heart of West Campus is open again and alive with more activity and energy than ever.

After three years of watching the massive transformation through construction fences, faculty, staff and students are finally getting a chance to stroll down the University of Cincinnati's new MainStreet. In fact, they aren't just passing through. They are stopping, eating, gathering, taking in movies, enjoying art and, most important, staying after dark.

As hoped, the unveiling of the new elements of MainStreet -- Tangeman University Center, Joseph Steger Student Life Center and large new open spaces -- has sparked a complete makeover of the social culture at UC. In addition to opening up countless new opportunities for gathering between classes, the MainStreet concept is moving UC away from its old commuter-campus mentality and toward a 24-hour community. It has given students, groups and campus organizations a brand new venue to assemble for social activities, entertainment, meals or just a quiet place to study.

MainStreet, a merging of both conceptual and physical changes, is the $233 million student life portion of UC's 15-year-old Master Plan to reinvent the campus. Opened with a gala celebration following UC president Nancy Zimpher's inauguration, MainStreet is actually not a street at all, but a pedestrian-friendly district where both architecture and programming encourage interaction outside the lecture hall.

The district cuts a diagonal swath through the center of main campus from University Pavilion near the western edge, through TUC, the Steger Center, the Campus Recreation Center, continuing into Sigma Sigma Commons and terminating at the Jefferson Residence Complex on the east. Until recent years, Master Plan projects focused on building academic facilities, converting land into open green space and developing a pedestrian-friendly campus. MainStreet, however, represents the Master Plan's fourth imperative -- quality of life.

"Like cities throughout the nation and the world, our university community now has a healthy and vital MainStreet,” says Zimpher. "Our newly modernized Tangeman University Center and our brand new Joseph Steger Student Life Center once were mere ideas that grew out of the collective thought of our campus community. Their new and impressive mark on our landscape today represents a visible testament of the transition from aspiration to reality."

MainStreet will be complete when the new Campus Recreation Center opens, but here is your guide to what's open for business now.

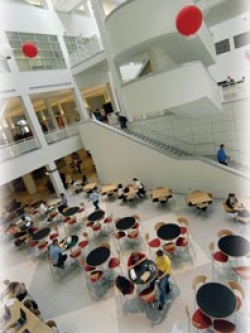

Light now pours into TUC from the skylight that surrounds the old clock tower. The new TUC was designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects of New York with the Cincinnati firm GBBN Architects.

For some, it was a curious new sound. For others it was a pleasant throwback. But for everyone, the return of the Tangeman University Center's clock tower bells was a melodic invitation to take back the social hub of campus.

Silenced by three years of construction, the University of Cincinnati's most familiar visual symbol, the TUC cupola, regained its charming chime the spring of 2004, just days before the gates of MainStreet opened to faculty, staff and students seeking their first glimpse of the reborn student union. TUC was shuttered and the area around it cordoned off in 2001 to allow for the facility's complete restoration and expansion. Judging by the reaction, it was worth the wait.

They came, they admired, but mostly they ate.

"That first and second day the TUC food court was open, there was so much business that they actually ran out of food," UC architect Ron Kull says. Most lined up for the food court's fare at Tortilla Fresca, Wendy's, Gold Star, Freshens and Pizza Hut, while many swung through Quick Mick's for a grab and go. Others hungered for a more sophisticated eating experience and enjoyed Mick and Mack's Contemporary Café, offering table-service dining with a panoramic view of McMicken Commons and a fresh-air patio alternative.

Since TUC opened in two stages -- the south wing in 2003 and the north wing this year -- most had already seen the rebuilt zinc-clad facility that houses the UC Bookstore and the 888-seat Great Hall. The north wing, however, remained under wraps for several more months. And considering campus was starving for social space and many had a vivid memory of the old TUC, the rechristening of the north wing created more buzz than any opening on campus in years.

About half of TUC's 67-year-old shell remains visible from the outside, as does the building's iconic elements -- the clock tower, though now sitting on a glass roof, and the four-column Greek Revival facade that faces McMicken Hall. The interior view of the building, however, is vastly different from the way students left it in the spring of '01. Upon entering TUC's north wing, visitors are met with a sensational 90-foot atrium that was created by literally gutting the old student union.

Upon entering TUC's north wing, visitors are met with a sensational 90-foot atrium that was created by literally gutting the old student union.

"It was like they took a core drill and went right through the center of the building to open it up," Kull says. "When the sun is out, and it comes through around that clock tower, it is unbelievable in that space. It looks light and airy rather than dark and dingy. The primary comment from students was that (the old) TUC was dark. So the design architect's main thrust was to get more sunlight into it. That's how the atrium and skylight came about."

Russell Curley, director of educational services, sums up his impression of the building's dramatic evolution rather simply. "Night and day," he says. "There are so many bright and open spaces. It is just like two different buildings. When alumni see this, they are going to be overwhelmed."

Not surprising, the glass-top roof that surrounds the cupola has become a central point of conversation, mostly because it gives passersby the impression the clock tower is somehow suspended precariously.

"The beauty of it is you are playing a little architectural game," Kull says. "When you look at it from the outside you think, ‘Well, how is that thing supported? It has got all that glass around it'."

From beneath, however, one can see all 90 feet of the interior structure holding up the massive clock tower. In fact, the support system is the central visual element within the atrium that draws the eye from top to bottom. Kull says he and the designers were pleasantly surprised when crews tore out the old ceiling to reveal salvageable roof supports.

The 888-seat Great Hall in Tangeman serves as programming space for everything from comedy acts to student orientation.

"Those are not heavy structural members like you might expect," he says of the supports. "They are pretty light elements, and it gives you a little web up there, almost like a spider web. It reinforces the airy quality of the whole interior."

Past the food and the architectural accoutrements, the new TUC also offers the campus community the chance to relax in its first-floor Catskeller game room, take in a $2 movie in its 200-seat theater or simply gather in one of 20 fourth-floor breakout rooms that overlook campus on all sides.

"TUC was one of the more anticipated openings since the Master Plan began (1989)," Kull says. "It (and the rest of MainStreet) represents the fourth imperative of the Master Plan, which is quality of life."

Planners preserved TUC's original four-column facade that faces McMicken Hall.

Devoid of a campus student union before 1937, UC leaders constructed Tangeman University Center that year on top of an old parking lot. The Union, as it was then known, was a much-needed addition as it provided a place for dances, lunches and meeting space for student clubs and organizations.

By 1965, the popular building was expanded to include the south wing and bridge area at a cost of $3 million, a million of which was donated by Mrs. Walter Tangeman. In return for her gift, the entire facility was named for her son, Donald Core Tangeman, who had been killed in action in World War II.

The facility was closed in 2001. The old south wing and bridge were leveled, and a new south wing was constructed, while the north wing underwent its dramatic transformation.

A pair of skywalks connects the western tip of the Steger Student Life Center to a renovated Swift Hall.

What's 40 feet wide, 500 feet long and smells like coffee beans?

The long and slender Joseph Steger Student Life Center, which reenergized the urban core of West Campus this spring as patrons quickly filled the innovative facility's offices, business center, computer lab, art gallery and, of course, Starbucks.

Named for former UC president Joseph Steger, the Student Life Center, which steps down the heart of MainStreet, is one of the most complex design structures to open at UC since Frank Gehry's curvy-walled Vontz Center for Molecular Studies graced East Campus in 1999.

"From an architectural standpoint, it is an extremely difficult building to design because it is so slim," UC architect Ron Kull says. "You have to think about two things: Where is the space you occupy? And where is the space for circulation?

"It was a feat for the design architects to design it in such a way that it doesn't just become all circulation space. And then they had to transition all the various grade drops. There is over a 50-foot grade drop in elevation from one end to the other."

A wall of windows on the south side allows daylight to flood the unique structure's interior and also provides those inside with impressive vistas of Nippert Stadium, McMicken Hall, TUC, the Campus Recreation Center and Varsity Village. Conversely, the interior lighting spills out onto MainStreet open spaces at night creating a warm glow that Kull compares to Vail, Colo., after sundown.

As planners hoped when devising the $238 million upgrade, MainStreet has awakened an after-hours energy at UC. Instead of immediately heading off campus for social events and entertainment, more students are sticking around for dinner and a movie in TUC, followed by a late-night caffeine pick-me-up in the Student Life Center's two-story Starbucks.

Interior spaces within the Student Life Center include a two-story Starbucks.

The gourmet coffee chain occupies the building's eastern tip. Approximately 500 feet west, taking up the opposite end of the building, is the 100-seat computer lab that now allows students 24-hour access to high-end PCs and Macs, a multimedia editing room and wireless networking. Sandwiched between those big-draw amenities are Subway, the bookstore's satellite business shop, the art gallery and key offices for student life, student government, student organizations, the Women's Center, the Wellness Center and others.

The design of the ground-level Phillip Meyers Jr. Memorial Gallery makes it a compelling place for local artists to display their work, particularly UC's fine arts students eager to get their pieces before an audience.

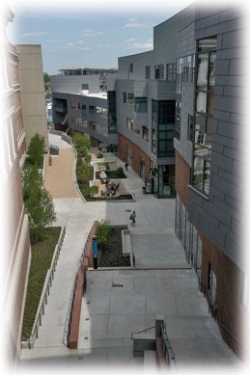

The Mews open space, running between the Steger Student Life Center on the right and the engineering buildings on the left, is an intimate setting for conversation or a relaxing lunch.

By now, MainStreet's open spaces have been absorbed into the University of Cincinnati's regular routine. The paved courtyards, grassy areas and granite seat walls are dotted with people talking, having lunch or passing through on their way to class.

A curious thing happened, however, when the chain-link construction barriers that walled off the interior of campus first fell in April.

"It was funny," says Leonard Thomas, project manager of landscape, design and construction from the UC architect's office. "When MainStreet first opened, it was as if the fences were still there.

"We probably could have done some sociological evaluation. It became almost Pavlovian. Students were so conditioned to that labyrinthine kind of meandering around that it took them some time to step beyond the non-construction space."

Though fences remain around MainStreet's final attraction, the Campus Recreation Center, the main corridor of West Campus has reopened and filled with life. Today it is foot traffic instead of cars traversing the area. The road is gone; walkways, gardens and new buildings have supplanted what was once Campus Drive.

"This whole metamorphosis is really a transformation that makes the pulse of the university much more electrified and active instead of passive," Thomas says. "Now if you go out there, it is incredible. There are corridors of opportunity and spaces of destination."

Students are again sunbathing on McMicken Commons, chatting on the steps of TUC, and walking down MainStreet between TUC and the Steger Student Life Center. Those looking for a more intimate area to study or talk are finding their way to the Mews, a series of tiered garden-like courtyards that terrace down the narrow strip bordered by the Student Life Center on the south and Swift, Baldwin and Rhodes halls on the north. One of the most popular features of the Mews has become the salvaged architectural pieces installed there.

The new Bearcat Plaza, surrounded by TUC, the Steger Center and Nippert Stadium, is becoming the outdoor epicenter for social life on campus.

Perhaps the most engaging new open space is the triangular area wedged by TUC, SLC and Nippert Stadium, known as Bearcat Plaza.

"Bearcat Plaza presents a great opportunity to see and be seen," UC architect Ron Kull says. "It is kind of like sitting on the old TUC bridge when everybody used to hang on the sides. This is the same kind of place where you can have a band at lunchtime or a concert on Friday night. Or kids can just hang out there on a sunny day underneath the trees."

The finishing touch to the Bearcat Plaza development includes taking down the Nippert Stadium restroom wall north of the press box to open up the view into the football venue and beyond. Four brick columns will then be erected in its stead to create a natural backdrop for a Bearcat Plaza stage.

Kull says the intent is to create public squares that invite intellectual discussion, social interaction and entertainment. "If you go back to our Master Plan, one of the things we have always said is there is as much learning that goes on outside the classroom as goes on inside the classroom."

Though it was demolished four years ago to make room for University Pavilion, Beecher Hall has resurfaced on campus in the form of architectural relics.

Beecher was originally constructed in 1915 to serve as the women's gymnasium and later evolved into an important administrative facility. Today, however, the building has been reduced to three column capitals at rest in the Mews, the open space at the northern foot of the Steger Student Life Center. Nonetheless, these interesting pieces of landscape art will forever remind the campus community of a small piece of its history.

![The placement of column capitals [top] from Beecher Hall and the crest from Swift Hall’s annex building [above] within the Mews connects today’s students with those of UC’s past. The placement of column capitals from Beecher Hall and the crest from Swift Hall’s annex building within the Mews connects today’s students with those of UC’s past.](https://magazine.uc.edu/issues/0904/mainstreet/jcr%3acontent/MainContent/textimage_9/image.img.jpg/1308688749786.jpg)

The placement of column capitals [top] from Beecher Hall and the crest from Swift Hall’s annex building [above] within the Mews connects today’s students with those of UC’s past.

And just up the stairs from the Mews is a second example of careful construction salvage. The seal from the Swift Hall annex building now rests in the scenic area known as the Baldwin Arch.

"These provide a whimsical reminder of UC's past," landscape architect Leonard Thomas says. "It is important to recognize that a university is a place that has a historical context, and it needs to be preserved."

In addition to Beecher and the Swift annex, other recent structures to crumble under the wrecking ball include the UC bookstore, Laurence Hall, the Old Service building, the West Campus power plant and the brick smokestack. Salvaged from those were columns, dentil molding and a door surround from Beecher, the crest from Swift, the door surround from Old Service and the massive terra-cotta UC seals from the smokestack.

"We have saved a number of pieces from buildings that we have demolished with the idea that we would get a chance to use them again someplace," UC architect Ron Kull says. "All of those artifacts give students an appreciation for what was here, even though they weren't."

University Pavilion houses OneStop Student Services.

The "UC Shuffle" officially halted with the December, 2002 opening of the $32 million University Pavilion. To keep students from shuffling back and forth across campus to conduct business in six different buildings, more than a dozen student-service offices moved into the new six-story building on a site formerly occupied by Beecher Hall.

"What we have created is leading edge in all of the country," says Mitchel Livingston, vice president of Student Affairs and Services. In one location, students can now register, check grades, drop and add classes, pay tuition, apply for financial aid, obtain student health insurance, discuss disability services, obtain academic counseling, seek career guidance and more. Better yet, most services can be obtained by talking to a single cross-trained professional in a mini-living-room "pod" at OneStop Student Services.

Operating as the university's front door, the Pavilion also contains the new University Visitors Center and executive offices for the president, the Board of Trustees and most of the vice presidents. A bridge connects the building to the College-Conservatory of Music and TUC.

Jefferson Residence Complex is surrounded by green spaces.

The block of campus where you may have once played tennis is today occupied by the Jefferson Residence Halls, a pristine suite-style dorm complex.

UC welcomed the first students into the 580-bed complex in 2002. In keeping with UC's Master Plan, the $39 million improvement along Jefferson Avenue boasts low-rise living in an atmosphere far different than many will recall. Instead of stretching into the sky, these dorms extend outward.

"This facility has increased amenities and privacy over what alumni would remember from their residential hall experiences," says Dawn Wilson, director of residential education and development.

"Nationally there is a trend to build smaller housing units that have a greater degree of intimacy in the community. Things are not so large and anonymous. They are smaller, more familiar and more personalized."

What has students lining up to live there is the suite-style accommodations. Most suites consist of two double bedrooms, a private bathroom, a common living area and a combined microwave/refrigerator unit. That's welcome relief for those used to sharing bathrooms and living areas with an entire floor of residents.

Students also like the idea that they can sign a year-around lease and stay on campus through the breaks rather than packing and moving each quarter. The rooms in the buildings were divided among first-year students, honors scholars students and student athletes.

The Jefferson Complex consists of two interconnected buildings, Schneider Hall and Turner Hall, named in honor of engineering Dean Herman Schneider, who founded co-op education at UC in 1906, and Darwin Turner, UC's youngest graduate. Turner earned his bachelor's degree in 1947 at age 16 and is considered a leading writer, editor and critic of African American literature.

The completion of the Jefferson Complex was the first milestone of the university's MainStreet project, a constructive effort to transform the center of campus with new dining options, cafes, retail shops and modern housing.

"One of the most important things the university wants to accomplish is to increase a sense of community on campus to improve the quality of campus life," Wilson says. "Part of how you do that is to make a greater amount of campus housing available and attractive to students."

The Jefferson Complex brings UC's total capacity for on-campus undergraduate housing to about 3,100. Capacity for an additional 700 will be added when a private housing development opens off campus and an additional suite-style facility opens on campus.

Recreation facility completes MainStreet

Last to make its grand entrance on MainStreet -- but right on schedule -- the University of Cincinnati's new 350,000-square-foot Campus Recreation Center will be worth the wait. Its pools, courts, fitness equipment, dining options, classrooms and living spaces should all be ready early in 2006.

Student suites atop the recreation center command views of Campus Green and Burnet Woods.

In fact, the center's suite-style housing units atop the building are expected to open in time for fall quarter '05. The 227-bed development, commanding "a cool view over Burnet Woods," according to university architect Ron Kull, is expected to be much enjoyed by the upperclass students for which it has been designed.

What could be more convenient than a room at the top of the recreation facility? Imagine a central location on campus, a quick morning workout on the indoor track or a dip in the pool, a healthy breakfast at the juice bar or marché restaurant, a stop at the convenience store for an extra notebook, then off to class -- perhaps in one of the six state-of-the-art electronic classrooms inside your building.

Facilities in the new center, which replaces the razed Laurence Hall, will open as each is completed. In addition to the natatorium with its eight 50-meter lanes, there will be a leisure pool and whirlpool. The gym will offer six basketball and eight racquetball courts. Weight training with a variety of free weights; cardio machines such as treadmills and exercise bikes (elliptical, recumbent and stationary); and "selectorized" nautilus-style machines are among other choices.

From the climbing wall to new locker rooms, aerobics classes to Spinning bike sessions, everything in the center has been planned to be state-of-the-art to appeal to UC students, faculty, alumni and staff.

"Students will be members through their Campus Life fee," Steve Sayers, associate vice president for Campus Services, points out. "Others will be able to join for a very competitive fee."

When all that exercise in the new University of Cincinnati Recreation Center works up an appetite, several options are close at hand. Fitness enthusiasts can choose healthy drinks, such as smoothies and nutritional supplements, from the juice bar; fresh produce and take-home meals from the convenience store; or typical soft drinks and snacks from vending machines. Even more attractive options are two full-dining facilities.

![Courts in the Campus Recreation Center [top] will accommodate six basketball games at once, and eight swimmers can test their speed against one another in the natatorium [above]. Courts in the Campus Recreation Center will accommodate six basketball games at once, and eight swimmers can test their speed against one another in the natatorium.](https://magazine.uc.edu/issues/0904/mainstreet/jcr%3acontent/MainContent/textimage_14/image.img.jpg/1308762330554.jpg)

Courts in the Campus Recreation Center [top] will accommodate six basketball games at once, and eight swimmers can test their speed against one another in the natatorium [above].

A marché, similar to the popular MarketPointe restaurant near Siddall Hall, puts an even greater emphasis on "presentation cooking," according to Steve Sayers, associate vice president for Campus Services. "Virtually all of the food production and preparation -- essentially everything but bulk pasta dishes -- will be done in the front of the house, not behind the scenes," he explains.

The 400-seat restaurant will be able to offer some new types of international dishes because of the installation of two very large pieces of cooking equipment that rarely are seen together on university campuses: a brick oven ("pizza, breads and desserts") and a Mongolian wok. "This wok is about 10 times the size of the one you might have at home," Sayers says. "It will be used primarily for chicken and steaks."

A late-night option, the Stadium View is a retail restaurant that overlooks Nippert's end zone. With the impressive view, seating for 160-plus and a similar but more upscale menu than the marché, it will please customers seeking the perfect place to entertain family or meet friends, especially those interested in Big East football.

"By the time we get all the landscaping finished for the recreation center, it will probably be between January and spring '06," university architect Ron Kull says. "We’ll have a major opening gala that spring, to celebrate that all of MainStreet is fully operational."

Link:

View design drawings by Morphosis

Tangeman University Center

* Design -- Gwathmey Siegel & Associates Architects of New York with local firm GBBN Architects. Structural engineering by THP Limited Inc.

* Cost -- $50.8 million

Joseph Steger Student Life Center

* Design -- Moore Ruble Yudell Architects and Planners of Santa Monica

* Cost -- $26.2 million

Swift Hall Renovation

* Cost -- $11 million

Campus Recreation Center

Under construction, to be completed by spring 2006. New housing scheduled to open in fall 2005

* Design -- Morphosis of Santa Monica, in partnership with KZF Design Inc. Structural engineering by THP Limited Inc.

* Cost -- $102.5 million

MainStreet Open Space

* Design -- Hargreaves Associates and local partners Glaserworks

* Cost -- $21.6 million

Infrastructure

Underground mechanical, plumbing and electrical utilities and communication systems

* Cost -- $21.7 million

Total: $233.8 million

The majority of the cost of the MainStreet project is paid for by student fees and the rest is supported by state funding, gifts and rent.