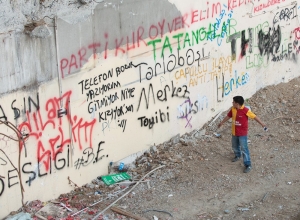

Caught in the clash

Journalist captures history in Turkey

by Barbara Blum

In the midst of a violent conflict between protesters in Istanbul and the Turkish government, a local man heaves a Molotov cocktail. Capturing the scene in words and photographs is Keith Rutowski, A&S ‘09, a graduate of the UC journalism program who decided to move to Turkey only a few weeks earlier.

His amazing photographs are a result of preparation and serendipity. After some contemplation, Rutowski and his bride, Allison Clarridge, A&S ’11, decided they wanted to live abroad. “We are both passionate about travel,” Rutowski says, “and my wife was interested in trying to teach English as a second language.” His work as a freelance fact-checker for Smithsonian magazine and National Geographic digital media was easily transferable. They arrived in Istanbul on May 15, 2013.

On May 31, the unrest in Turkey began after police broke up a protest against the demolition of a park — a traditional gathering point, a popular tourist destination and one of Istanbul's few remaining green public spaces. More broadly, some were also unhappy with the Turkish prime minister’s policies.

Rutowski happened to be at the right place at the right time, but his preparation as a journalism student and News Record staffer made him ready to take on the challenge as an eyewitness to a world event. “It's no easy task. And while I've always had a deep respect for the great photojournalists who shoot resistance movements, uprisings and wars, my wonder and admiration for them has grown immeasurably since attempting to shoot this.”

Rutowski’s journalistic persistence and fortitude are partly the responsibility of former News Record columnist Charlie Stix, A&S ’49, whose scholarship for journalism students benefitted Rutowski.

Stix is a story himself. Because of his strong support of UC journalism since 2005, one might expect him to be a longtime, hard-boiled reporter. The small, elegant man, however, was a vice president for U.S. Shoe for more than 30 years.

His commitment to the UC program stems from his time as a writer and columnist for the student newspaper in 1948 and ‘49. “I felt the News Record was the most important thing that happened to me at UC,” Stix says. “It taught me so many things — how to handle people, how to handle disgruntled professors, how to handle administrative people.”

Stix believes those life lessons learned while on the newspaper were so important, he wants students today to benefit. “It was very important for me to give back,” says Stix, “and I was fortunate enough to be able to do it.”

Pledges and planned gifts to the McMicken College of Arts and Science can be designated to a specific program or purpose, such as the journalism department. Stix recently started a scholarship program to support students interested in investigative journalism.

The following excerpt first appeared in a blog posted by Keith Rutowski on www.worldpolicy.org.

Covering the Gezi Park crackdown in midst of tear gas, a stampede, Molotov cocktails

By Keith Rutowski

All photos by Keith Rutowski

GEZI PARK, Turkey -- I had only been living in Istanbul for little more than two weeks when I tasted tear gas for the first time. I spent most of the month of June in Gezi Park and the surrounding streets, trying to capture telling moments within the swirl of events.

It was a month with moments of clarity and bewildering contradictions. It is only now that I’ve begun to process what I saw and to try to make sense of what transpired.

After the first violent police crackdown on May 31, the crowds grew larger, messier and bolder. Demonstrators who had hoped to prevent the destruction of the roughly 9-acre park in the city center were still around, but they were now flanked in Taksim Square by individuals hoisting political party signs and demanding the prime minister’s resignation.

I spent many evenings walking amidst the banners, vendor carts and dance circles, studying a scene that fluctuated between a festive celebration and a maelstrom of indignation and diverging agendas.

For a period of time, Gezi became a world unto itself, with an atmosphere distinct from the square and surrounding streets. While the streets served as a battleground for police and protesters, the mood in the park was stable and, at times, reflective. I would often wander past the makeshift library, weave my way among the tents offering free food and stop to watch a musician strumming a guitar or a couple quietly reading.

During the month, I stood among the police waiting near a 19th century palace for a potential confrontation and followed young people in helmets and goggles as they confronted police on main thoroughfares, then retreated, gagging and eyes burning, into Istanbul’s steep side streets.

I was caught in a stampede in Gezi when police fired canisters into a dense crowd. The park was so clogged with people that the walkways were obstructed, and people began to push in all directions as they tried to fight their way out. I thought there was a distinct possibility that I might suffocate or lose consciousness in the gas. In reality, this scene in the park probably lasted five minutes, but it felt endless.

These are far and away the most difficult circumstances I’ve encountered. I’m spending as much time in the field avoiding tear-gas canisters, stones, fireworks and Molotov cocktails as I am in composing shots.

In trying to get closer to the action, I have, on a few occasions, found myself caught in the middle of the clashes. The confrontations have largely been occurring in open spaces where it’s sometimes difficult to take cover, and even when you do find some, it doesn’t always guarantee safety.

The defining moment during the protests came when one man chose to stand silent and motionless in Taksim Square for several hours and in doing so inspired hundreds of others across the country to imitate the act of civil disobedience. Although he and the other “standing men” were eventually removed by police, and though water cannons and tear gas would later make a brief return, it seemed as though this marked a turning point in the tenor of demonstrations. It seemed that the people who had been moved to the streets to make their voices heard now felt they were saying the most by saying nothing at all.

For now, life in Istanbul has mostly returned to how it was before May 31. One reminder of the largest civil uprising in the history of the Turkish Republic occurs at around 9 p.m. every day — when people step out on their balconies with pots, pans, spoons and whistles to make certain that the events of the past few weeks are not forgotten.

Additional scholarships and supporters of the

McMicken College of Arts & Sciences

Department of Journalism

- Lee Evans Memorial Fund

- Mary Linn White Scholarship in Journalism, daughter Lora Linn Swedberg contributor

- David and Michael Altman Scholarship, father David and son Michael Altman contributors

- Jon Hughes Scholarship

- Scripps Foundation scholarship, Sue Porter administrator

- Jim Knippenberg Society of Professional Journalists Scholarship, daughter Michelle and her husband Denny Kramer contributors

Past Issues

Past Issues