Let there be light

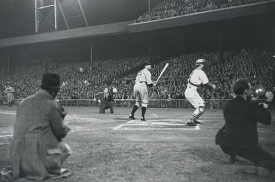

Crosley Field was damp and chilly from the previous day's rainstorm, and a veil of smoke hung low to the ground from the fireworks eruption just minutes before. It was 1935, and 20,500 Cincinnati Reds fans waited in darkened silence as President Franklin Roosevelt flipped a gold ceremonial Western Union telegraph switch at the White House, sending a signal to Cincinnati. Within seconds, an explosion of light drenched the stadium as 632 floodlights illuminated a major league ballpark for the first time in history.

At the time, nobody knew just how transformative the move to play after sunset would be for America's past-time. But within a few years, multiple stadiums in the league were aglow.

For one University of Cincinnati alumnus, Crosley Field's first shining moment -- May 24, 1935 -- took on such a personal significance that he's spent the last quarter of a century piecing together the history of night baseball. More than anything, Robert Payne, A&S '67, MA (A&S) '71, wanted to shed his own light on a particular contribution of his father, Earl Payne, Eng '26, who had helped design professional baseball's first lighting system.

Payne's quest started in 1984, years after his dad passed away, as he sorted through an old family suitcase.

"I found a little aluminum canister -- actually, several of them along with other negatives and photographs," Payne says. "One of them was an entire roll of film from a Reds vs. Phillies game with light towers all over the place."

His father, who worked as an electrical engineer at Cincinnati Gas and Electric for 14 years prior to a long military career, never took much of an interest in sports. So why had he taken an entire roll of baseball pictures at night?

"I was quite surprised to see the Phillies and the Reds," Payne says of the photographs. “And I knew it was old-time baseball. I could tell from the right-field wall.” In 1938, Crosley’s dimensions were changed, decreasing the distance between home plate and the right-field wall to 366 feet. “But in all my dad’s photographs, the right-field wall was marked 377, "Payne says. "I then realized these photographs were taken sometime before 1938."

With his curiosity piqued, Payne turned to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., and eventually tracked down Billy Sullivan, the former Reds first baseman who appeared in his dad's photos, in Sarasota, Fla. "I asked, 'Did you play baseball for the Reds?' and he said, 'Yes, I played for one year -- in 1935.'"

Payne discovered night games began in 1935, and Cincinnati only played seven night games that year. As it turns out, there were eight teams in the National League, and the Reds played each of the other teams once. "All the numbers agreed," Payne says. "And I knew. This was it. This was the first night game."

Needing more proof that his dad not only helped design the lights but also photographed professional baseball's first night game, Payne went in search of more evidence.

"I remember my mom telling me in the '50s, when I was a teenager, that my dad designed the lights of Crosley Field," Payne says. " But I wanted to be able to know what I had was real, and I like to have more than one source."

Payne found one person who changed everything: Wayne Conover.

Conover worked as a lighting technician side-by-side with Earl Payne, one of the CG&E engineers who designed the lighting layout for Crosley Field, as well as the original lighting layout for UC's Nippert Stadium.

Payne met Conover in 1989. "He remembered my father, and he made it possible for me to have details I never could have had otherwise," Payne says. "My dad, along with two other engineers, decided how many light towers, where to place them, how high, how many floodlights and spotlights."

Understanding the importance of their work requires some context of the state of baseball in the '30s. The Reds were broke and in last place in the National League in 1933 and '34. The major leagues were almost universally opposed to night baseball, but the minor leagues were attracting working people to night games and making more money -- sometimes 10 times the amount of a major league day game.

When Powell Crosley bought the Reds, general manager Larry MacPhail convinced him to put in a permanent lighting system to generate more revenue by bringing in evening patrons. The gamble quickly paid off when the first night's attendance tripled that of a day game.

The Reds revenues increased, they came out of bankruptcy and by 1939 had made it to the World Series. By the time the United States entered World War II, 11 of 16 major league clubs had installed lights, and a new era began for baseball fans.

Discovering his father's contribution to professional baseball inspired Payne to have his dad's photographs copyrighted and sent to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1990. A retired U.S. Army chaplain, Payne kicked around the idea of writing a book about the history of night baseball and his father for years, and in 2000, he finally started writing but never fully dove into the process as he had planned.

"Three and a half years ago, my sister said, 'You' ve got all this information, why don't you finish the book?'" Payne explains. "I was 64 years old and retired. I had no reason not to, so I pulled it all together and finally wrote a book."

Payne's book, "Let There Be Light: A History of Night Baseball," shows the evolutionary process of night games and the lighting of ballparks in the major and minor leagues.

Jayna Barker is a senior journalism student at UC and an intern with "UC Magazine."

Published in 2010.

LINKS