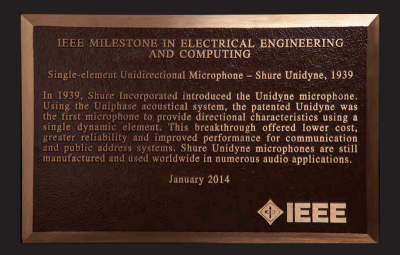

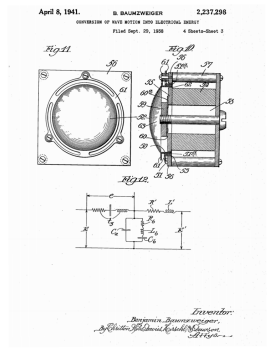

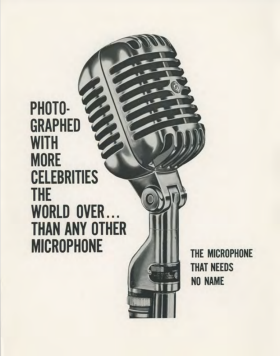

“The Unidyne was Bauer’s first patent, and today the Uniphase principle which he invented is used in nearly every directional microphone around the world,” says Michael Pettersen, director of applications engineering, and corporate historian for Shure Inc.

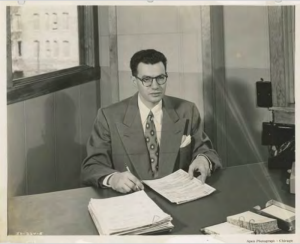

Bauer on the run

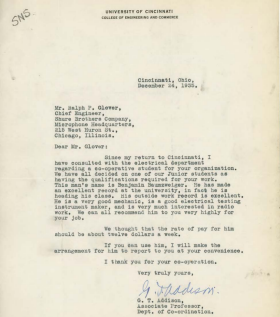

Benjamin Baumzweiger (who would later change his name to Bauer) was born in war-torn Odessa, Ukraine, in 1913, and endured a childhood that could be described as a cluster of chaos. Bauer’s family owned a lumberyard in Sevastopol, Ukraine, during the Russian Revolution and was forced to turn ownership over to communists. His great-grandfather was not pleased by the situation and wanted to keep the lumberyard in the family’s ownership, but his attempt at reclaiming the lumberyard was fatal.

“They shot him on the spot,” recalls Dr. William Baumzweiger, Bauer’s youngest son. “At least that’s one story, the other is they shot him when he was going to temple.”

As a result, Benjamin spent much of his childhood fleeing from country to country due to war and anti-Semitism. He later changed his last name after becoming a U.S. citizen. Bauer and his family called four different countries home by the time he was 12 years old, and his family eventually settled in Havana, Cuba, which had a large population of Jewish immigrants in the 1920s and 1930s. At the time, the United States had set a limit on the number of Jewish immigrants allowed to enter the country, and the overflow often went to Havana.