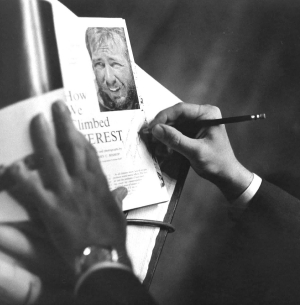

By Barry Bishop, A&S '54

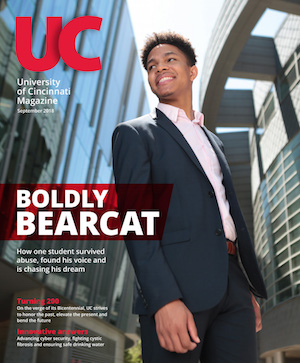

University of Cincinnati

Commencement address

This address (abridged) was given by Barry Bishop at the University of Cincinnati commencement on June 12, 1994, the same event at which he received an honorary degree.

You might be amused to know that in 1954, when I received my Bachelor of Science degree here at the University of Cincinnati I was Ivy Day Orator. Very wet behind the ears, I pontificated that, "As college graduates about to be turned loose into the world, we are constantly told that the world is in a sad and sorry state and that the hope of the future rests with us. We are told that it is our duty to save the world from final consuming catastrophe. This thesis has been stated many different times in many different ways... ad nauseam.

I chose to be more positive, yet there has always been, and probably always will be cause for concern. Real-time communications continues to shrink our world, while increasing our awareness of the raping of our planet's human and natural environments. In the face of this information overload too many people are becoming callous, indifferent, uncaring and purposeless. Camelot continues to escape us!

Bob Hope once took a different tact at a graduation. He regaled his audience with what awaited them in the cold, tough world that lies outside the hallowed halls of academe and ended his remarks with the advice: "Don't go!"

I have also noted that brevity on an occasion such as this gets high marks--particularly with those graduating. Art Buchwald delivered the shortest address I know of. He stood up, said "We've done a pretty damn good job of it -- now don't you screw it up" -- and sat down.

Although I can't promise to be as brief as Buchwald, I continue -- after 40 years -- to refuse to buy into the "Doom and Gloom theme."

Instead, I would like to share with you this afternoon a few positive thoughts and experiences appropriate to my thesis, "Making Dreams Realities.” Hopefully, all of us here -- but especially you who are about to enter the real world -- are full of dreams -- dreams that demand visions! As a child growing up here in Cincinnati I had three vivid and recurring dreams that did indeed become realities.

The first one actually started as a bad scene -- the first spanking I can remember (at age 6 or 7). This was no doubt light-handed corporal punishment carried out by my father because I had cut out pictures of nubile, bare-breasted women from the pages of National Geographic Magazine without first asking permission. But I also began dreaming of one day working at the Society, for in my naivety I thought that everyone working for the Society spent all of their time on exotic expeditions. Later this dream became a reality, and I was disabused of my naivety.

The second dream occurred about the same time. It followed a lecture my parents took me to. I listened in fascination to Admiral Richard Byrd report on his most recent expedition to the Antarctic. "That's the life for me," I dreamed at the time, “Working with Admiral Byrd!" Sixteen years later that dream also became a reality.

The third was the most vivid and frequent of my youth -- climbing Mt. Everest. I had it first on the summit of Long's Peak (14,255 feet), in Colorado, when I was twelve. While dozing in the sun after reaching the top that August afternoon, I dreamed of climbing a peak over twice the height of Long's -- Mt. Everest – Chomolungma -- Goddess Mother of the World (29,028 feet). The scoffers with no vision might view it as nothing more than a boyhood dream of an unattainable goal. But great dreams can become realities. Such was the case for me, for as a member of the first American Mt. Everest Expedition in 1963 I did reach the Third Pole -- the summit of earth's highest mountain.

Past Issues

Past Issues