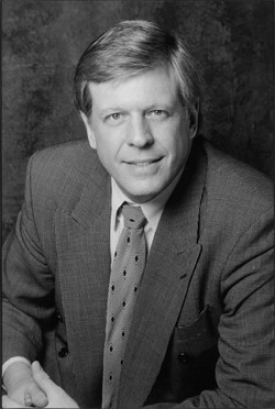

by Deborah Rieselman, originally printed in 2000

Larry Patterson stumbled into the hospital with a fuzzy recollection of a police baton swinging toward his head.

It was April 30, 1968, and racial tensions at Columbia University, New York City, were acute. Eight hundred students, both black and white, had been occupying five buildings for several days and, at one point, had held three school officials hostage.

On day eight, 1,000 police officers stormed campus, clearing 1,500 protesters and spectators in a little more than two hours. But the action was far from peaceful: 372 police brutality complaints, 148 injuries and 712 arrests occurred in what some writers have called "the largest police action in the history of American universities."

Life magazine immortalized images of students in suit coats with raised fists confronting protesters. But those photographs were taken from outside the buildings. No one had photos from the inside. No one, that is, except for Larry Patterson, A&S '66.

The University of Cincinnati alumnus was a member of the only news crew covering the event from the inside and capturing the action on film. He was doing what he did best, putting together a TV documentary -- a skill that would eventually earn him six Emmy Awards and nine nominations.

The last thing Patterson remembers about the occupation was exercising another one of his truly great talents -- opening his mouth.

"It was really a riot in the classic sense," he says. "I saw a cop clobbering some guy and said, 'You don't have to do that.' Then the cop hit me over the head."

It was a life-changing moment in more than one way. "The president of NBC later came to the hospital and said, 'We're going to take care of you, kid,'" Patterson recalls. Executives had already agreed to pay him $15,000 for exclusive rights to the footage plus $5,000 for every minute used locally or nationally, but then the network sent him on a number of impressive assignments and ultimately made him a producer of an innovative news show.

The story epitomizes Patterson's philosophy: "Life is about coincidences and being in the right place at the right time."

To begin with, Patterson had managed to enter the occupied Columbia building when a black, free-lance cameraman woke him up at 4 a.m. to say he could get a film crew in right then. Patterson did not stop to brush his teeth.

The timing was indeed perfect, yet at a casual glance, such luck appears to be a quality that normally eludes Patterson. A few months after the Columbia incident, he ended up hospitalized with another skull fracture, this one from a riot at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago. He was also at the Ambassador Hotel the night Bobby Kennedy was shot, and two Vietnam assignments revealed untold gore. In addition, a car accident in Australia decapitated his date and left him in a body cast and in and out of hospitals for three years.

Such "luck" started stalking Patterson early. At age 14, he discovered a Scout camp director after a suicide.

Although Patterson has grieved over much of the past, he also acknowledges that most of it turned into unexpected opportunities. The emotionally distraught Eagle Scout, for instance, was sent by a teacher to the Cincinnati Summer Opera "to take his mind off of things." Afterward, he sneaked backstage, and the stage manager, thinking he was part of the show, asked if he'd like to be an extra in "Aida."

The teen jumped at the chance to be a guard who had a spotlight moment in the middle of the triumphal scene. "There were 125 people in the pit, 200 people on stage and a packed theater," he recalls. "From top to bottom, I was one big goose bump. I can remember it like a calling. I said, 'This is what I'm supposed to do with my life.'"

His initial calling to entertainment, of course, did not come with a detailed map. He had much to figure out. To cultivate it, he took bus trips to New York and bought standing-room tickets to stage productions.

Still, he remained skeptical about making a living in entertainment, so he enrolled at UC in political science. For a student who had headed the state youth campaign for Nixon in 1960, the two fields were not such strange bedfellows.

"I was always torn between show business and politics," he says. "I realize now that there's little difference between the two. Both have lots of hype, promotion and fund raising."

Active with the UC Mummers Guild, he also helped found Young Friends of the Arts, now Enjoy the Arts, so young Cincinnatians could attend professional performances at reduced prices. After graduation, he entered law school on a scholarship, but lost it when his grades dropped from spending too much time sitting in on CCM master classes and rehearsing his Mummers Guild role as the male lead in "Funny Girl," the country's first amateur production of the Broadway musical.

The dean had tried to warn him about the play, but Patterson knew better. Or so he thought. He decided to take a year off to think a little harder.

Patterson was contemplating returning to the University of Cincinnati for a master's in theater management when the leading lady of a summer stock production, where he was assistant director, gave him some advice: "Television is the future, not theater." Her husband's offer of a research assistantship with his independent New York film company launched Patterson's career.

Of course, his early years in New York had some ups and downs. Sharing an apartment with actor Ryan O'Neal was a good example. "We totally furnished our apartment by scrounging furniture that was tossed out as garbage along Park Avenue," says the man who now lives in an Upper Eastside unit with a security guard in the lobby.

His career made a dramatic leap after selling the Columbia University footage. The summer of '68, he joined NBC news and the following January was named an associate producer of "First Tuesday," the nation's first magazine-format TV program.

Patterson produced, edited and directed interviews and segments for the show, most of them controversial, and received $15,000 a year. "I thought I had died and gone to heaven," he says.

Two years out of college with an unrelated degree, he worked 18-hour days to handle a substantial learning curve, but was thrilled at the attention he received for being "the youngest producer/reporter in the network's history," he says. NBC was equally thrilled with him when his first episode received an Emmy. Across the country, 265 newspapers carried a syndicated article with the headline "Larry Patterson Spells Youth."

Among highlights of his NBC stint was being on the news team that interviewed Queen Elizabeth II, Fidel Castro (the first news team allowed into Cuba in 10 years), 68 American expatriates in 16 countries and Sirhan Sirhan. The morning after the Sirhan interview aired, "the U.S. Justice Department's 'goons' struck," he says, "taking into custody box-loads of all of the footage, the outtakes, the transcripts and the producers' and writers' notes, never to be returned or seen again."

After NBC, his resume jumps around. For several years, he wrote, directed and produced in Australia, which abruptly ended when he became a car-wreck victim. He also produced the first revival of "My Fair Lady" on Broadway. "I was way out of my league with that," he confesses, "so I went back to what I knew best, producing independent television."

Although the 6-foot-4 blond earned six figures a year appearing in commercials (oftentimes with six auditions a day) in the '80s, his greatest successes were producing telecasts, three in particular: the Playboy Jazz Festival at the Hollywood Bowl, the world's largest pep rally in '82 in the Houston Astrodome with more than 100 million television viewers and the Houston Grand Opera's production of "Treemonisha," for which he won an Emmy in '86. Plus, in '87, he was executive producer of the NBC sitcom "You Can't Take It With You," a three-year show starring Harry Morgan.

Today, Patterson is pitching another sitcom, one for which he wrote the pilot. His company owns copyrights or options on 14 television projects and 22 screenplays.

Among current projects are a game show, three sitcoms, two dramatic series, two documentaries, two reality-based series, three adventure films, a mystery movie, several animated children's films, two fantasy adventures, five comedies, a musical drama, a period piece, a holiday TV special and six true-life dramas. Late summer was "pitch season" in the industry, and his arm got a good work out.

He admits to having an eclectic mix of work. "You can't limit yourself," he says. "You cannot be a specialist anymore. You have to have a lot of irons in the fire to hit that home run.

"I like the challenge that being independent offers us to find out how good we are," says Patterson, who took a former CBS executive as a business partner nine years ago. "It's like a decathlon, giving us the opportunity to discover how good we are in the producer/director niche, at camera work, at writing. It was a wonderful gift from God that I got to do all of it."

His projects, though diverse, share a commonality: "I try to do things with messages," he explains, "with an underlying Judeo-Christian ethic. We've got this bully pulpit, and if we're not using it, we're abusing it. It's our responsibility to leave this world a better place. We try to do shows that leave people hopeful and feeling better about themselves."

Although he finds producing enormously satisfying, the job has two aspects he dislikes: "You don't get a paycheck every week, and things can take forever to happen." Consequently, the profession has forced him to cultivate patience. It has also taught him a number of other lessons, the biggest of which has been the one most often reinforced since the police baton incident: "You have to ask the right questions at the right time -- and be able to keep your mouth shut when required."

Past Issues

Past Issues