by Mary Niehaus

In a restaurant near the University of Cincinnati, an ordinary-looking man seated with a few companions reaches automatically for the check. Scarcely glancing at the nearly $200 total and without a flicker of hesitation, he pulls a softball-sized wad of cash from his pocket.

"Here ya go," he smiles at the startled waitress, as he peels three $100 bills from his bankroll. "The rest is for you."

It could have been a scene straight from the movies. It almost was.

Film director David Anspaugh was among the diners, but his role did not call for paying the tab. "The props guy is the only one who carries money," he explained to Richard Friedman, special assistant to UC President Joseph Steger. "That's so he can work out cash deals on the spot when he finds the props we need."

That was just one of many Hollywood insights Friedman gleaned while serving as the university's liaison to film crews who brought their cameras, lights and sound equipment to campus in the last dozen years.

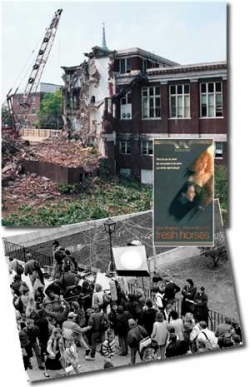

Anspaugh was the first of this wave, using the university as a major location for the romantic Molly Ringwald and Andrew McCarthy film "Fresh Horses" (1988). Others include "Eight Men Out" (1988, starring John Cusack as one of several ball players involved in the 1919 World Series scandal), "City of Hope" (1991, an urban corruption tale written and directed by John Sayles) and "Little Man Tate" (1991, easily the most successful of the lot, starring and directed by Jodie Foster).

The Oscar-winning actress came to campus to film UC as the unnamed university where an extremely gifted child (her son in the movie) attends classes. Foster, one of Hollywood's most powerful actresses, is a woman who speaks her mind -- as Friedman discovered.

"When I went out to meet the location manager for the movie, I noticed there was a woman with him," Friedman admits. "I didn't pay much attention; she was short, wearing jeans and a T-shirt, no makeup. As I'm chatting, it suddenly dawns on me that it's Foster.

"Later, when I was introducing her to our provost, I was joking with him that she was going to give the university a million dollars. 'Dick's been very helpful,' Foster retorted, 'but he lies a lot.'"

Jokes aside, Foster came to UC for a very specific look. One of the locations she liked was 127 McMicken, a classroom in need of some redecorating. Would UC permit the company to put Levolor blinds on the windows and paint the room Ralph Lauren green? Friedman hesitated; usually the university sanctioned a limited palette of pale colors. But the College of Arts and Sciences approved, and a spruced-up Room 127 stars as a quantum physics classroom in "Little Man Tate."

Beecher plays Baldwin

Moviemakers who film on campus are driven to find locations that mirror their ideas of how things should look, never mind reality. The interior of Baldwin Hall on the west campus, for example, became city hall in "City of Hope," and the venerable Walnut Street facade of the old College of Applied Science (CAS) doubled as part of a New York City street scene in "Eight Men Out." Less of a stretch was the use of a lecture hall in the Old Chemistry building for an engineering class in "Fresh Horses."

"I would say to a location manager, 'Tell me what you need,'" Friedman recalls. "He'd say, 'We need a room ... ,' and he'd describe the look he wanted. After I'd show them something, he'd explain that the decision was up to the director. Then he'd say, 'Show me something else.'

"That's how Beecher Hall (now demolished) became UC's engineering college in 'Fresh Horses,'" the administrator explains. "I don't know why they picked Beecher, when we had Baldwin Hall -- a perfectly good engineering building, with pillars and everything."

But campus buildings weren't the only stars from UC. Scores of students and a number of staff were drafted into "Fresh Horses" when the director realized he needed additional extras. A scene on the bridge between Beecher and Tangeman University Center was not only more realistic with a bigger crowd, it gave Friedman a brief cameo appearance as Professor Berg.

"We've got something special for you," the filmmakers told him when he joined the throng of extras. As an inside joke, they wanted to insert the name of one of the project's backers, Dick Berg, in the movie. So, as star Andrew McCarthy strides across the bridge, he greets another student, then says, "Mr. Berg, how are you, sir?" Friedman is seen for several seconds as he responds, "How are you?"

Past Issues

Past Issues