Hero and healer

"Shukran." The word means "thank you," and it's the first Arabic word an American soldier learns in Iraq -- because they hear it all the time, says Major Brad Wenstrup. "'Shukran doctor, shukran,' and they would place their hands over their hearts," he says.

For Wenstrup, a podiatrist and U.S. Army reservist, it's just one example of life-changing gratitude on a journey that took him from his surgery rooms in Cincinnati to Abu Ghraib Prison Hospital in Iraq. He served as chief of surgery for the 344th Combat Support Hospital in 2005-06, where Wenstrup and his fellow doctors oversaw detainee healthcare, primarily at the infamous prison. They also cared for troops and civilians, and his yearlong service has earned him numerous military awards, including a Bronze Star. It was a surprising twist for the doctor, who joined the reserves in February 1998 after practicing medicine for more than a decade. He had kept the idea of enlisting in the military on the backburner for several years, always mulling it over.

The jolt to action came when his sister was diagnosed with leukemia, and Wenstrup was a match for a bone-marrow transplant that saved her life. "Time was ticking by, and I thought, 'I'm not getting any younger.' I wanted to serve, so one day I just called 1-800-USA-ARMY and joined."

It was years, however, before Wenstrup would be called up for active duty. The tragedy of 9/11 struck, the Iraq war started … still no call. "One day, someone asked me, 'You think you'll go to Iraq?' This was in March 2005. And I said, 'I think I missed this war; they haven't called me yet.' That afternoon I got a call saying I'd be going to Iraq for at least a year."

Wenstrup quickly closed up shop at Wellington Orthopedics in Cincinnati and traveled to New York to join his unit. He found out there, at the airport, that he would be deploying to Abu Ghraib, the site now known for reports of torture and abuse of detainees at the hands of U.S. soldiers in 2003. He said the assumption by people back home that he was at the prison during those incidents irritates him, as he arrived two years later.

"I found out about those things when everyone else did. I was here. It was very wrong, and the military took care of it. Those people were in jail before I ever got there," Wenstrup says. "We knew we were walking a fine line, though, and I was kind of disappointed we didn't get more media wanting to come back and look at the good things we were doing."

Once there, Wenstrup and his colleagues were informed that their new homes would be prison cells, which he says were modified to resemble dorm rooms. Prisoners lived in tents. Prison bars were covered with plywood, offering a bit of privacy, though soldiers and Marines had to use a shower trailer and portable toilets. "Porta Johns in 130-degree heat are not pleasant places, but you can get used to anything. Who are you going to complain to?" he says.

Complaining about a lack of plumbing does seem trivial compared to other concerns Wenstrup and his comrades faced. The tent hospital they worked at was located within a large warehouse, which was attacked by mortars or rockets three to four times a week, he says.

Soldiers and doctors had to wear their armor every time they stepped outside the hospital, even to walk to the dining facility. The life and death risks were obvious. "We just started to think that if it's our day, it's our day."

But even in the midst of the uncertainty of war, the Iraqi people inspired Wenstrup. At one point during his service, his sister, Amy, asked him if he needed anything. He said he didn't.

"I told her, I wear the same clothes everyday, we're fed, and most days I'm not leaving the base. But the people here have nothing. They were under an oppressed regime and have had nothing for so long."

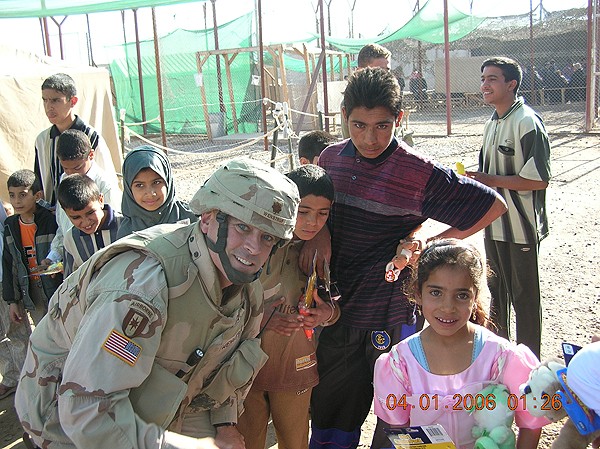

So his family organized support back home, and soon, donations came pouring in -- toys, school supplies and hygiene products from local companies, among them Cincinnati Bell, ProScan Imaging and Wenstrup's Wellington Orthopedics, as well as from tri-state churches and individuals. Wenstrup teamed up with the chaplain at the base to form Operation Goodwill Gifts, distributing the gifts to local Iraqi children.

The recipients were especially fascinated by yo-yos. "I tried to get them to take it out of the packaging and try it, and they wouldn't do it. They held on to everything they got because they had nothing, and they wanted to make sure they got it home. "The Iraqi people just want a safe environment like we have so they can raise their families."

Inspiration also came regularly from his daily duties and often in surprising ways. For instance, the 4-month-old daughter of one of the unit's Iraqi interpreters was wasting away from an unknown illness, and the doctors in Baghdad had given up on her. The wife of the hospital's anesthesiologist was a pediatrician in the U.S. and was able to diagnose the baby's cough over the phone. She had pneumonia and possibly a condition that caused her to reject her mother's milk. The answer was gluten-free formula.

"We were a combat-support hospital. We didn't have any baby formula," Wenstrup says. But a hat was passed among the soldiers at the hospital, and in a half hour, $400 was collected. The father traveled to Baghdad, found formula, and the infant began to thrive. For the next several months, a U.S. company provided gluten-free formula pro bono.

"Those were the good days," Wenstrup says. "On the other hand, I remember one Marine we lost on the table, and the anesthesiologist saying, 'I had breakfast with him this morning.' Or having to tell a group of Marines their buddy didn't make it. Those were the tough days."

The experience has been life changing for Wenstrup. "You come back, and the little things don't matter. You get a true sense of what's important in life and how lucky we are."

That's why even after returning home, his mission hasn't ended. Wenstrup has given dozens of presentations on his Iraq experience at events to raise money for the Ohio Disabled American Veterans, and he started the Thank America First Foundation to connect volunteers to ways to help the troops. Part of his pitch is to encourage people to serve their communities in any way they can, whether in uniform or not.

"The real heroes in our country are the people who volunteer and help each other," Wenstrup says. "I think a lot of people are looking for opportunities to serve. I always encourage them to get involved, because you never know where it's going to take you."

Issue Archive

Issue Archive