by John Bach

The deep thud of a jackhammer echoes across the University of Cincinnati's McMicken Commons. To those standing on the expansive green and facing east, campus appears to have fallen in on itself.

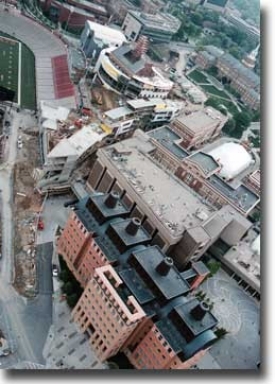

What was once the student union, Tangeman University Center, is now a mere shell, its steely girders exposed for all to see. Students, hemmed in by plywood and chain-link construction fences, trudge around the mess. And from his sixth-floor office, retiring UC president Joseph Steger has a bird's-eye view of the chaos he'll leave behind.

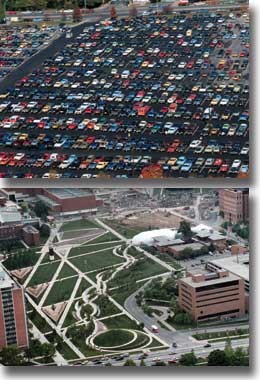

To visitors, UC may appear in shambles, one big hard-hat area. But to regulars, the work on TUC and the new MainStreet corridor through the heart of campus represents the culminating phase of Steger's most tangible legacy -- the Master Plan, a massive physical transformation he envisioned 14 years and $1 billion ago.

No doubt the era has been accompanied by growing pains. Still, most who have witnessed the Steger years will count 1984 to 2003 as a golden age of progress for this university, and not simply due to bricks and mortar.

The same span has seen widespread technological advances in the classroom, obvious efforts to improve service at every level, a dedication to social equity through an initiative known as Just Community and a commitment to laboratory discovery that has steadily produced knowledge and products of global importance.

Even those who do not view the last two decades so positively surely would agree it has been a period of extreme change. The numbers alone speak to the progress: 16 new buildings, several by world-renowned architects; a budget that has grown from $273 million to $753 million; and research funding that last year reached $260 million, compared to $30 million in 1984. Plus, the university endowment has grown from about $150 million to about $800 million.

Obviously UC's hyper-evolution is due partly to the fact that it was surrounded by a world that over the same time frame witnessed the end of the Cold War, the beginning of the digital age, years of unfettered economic prosperity and scientific revelations such as the mapping of the human genetic code. Regardless of whether UC has remained ahead of the curve or has orbited at the same rate as the rest of the planet, both are far different today than 19 years ago.

UC's Internet traffic, technology that was virtually nonexistent in 1984, amounts to 20 trillion bytes per month today. Yahoo Internet Life even ranked UC as the 32nd "Most Wired" campus in the country in 2000. Students and faculty using UC's wireless network can surf the Net in various locations on campus without a physical connection.

Historically speaking, information technology has reformed the classroom experience for the modern student. Hundreds of professors now use an online course-management system known as Blackboard, which allows students 24-hour access to materials, grades and even discussion groups. Instead of chalkboards and overhead projectors, faculty often connect with students through entirely online courses, paperless classrooms and streaming video. It is indeed a different place, both physically and virtually.

When Joe Steger took over as the university's leader in '84, the same year Ronald Reagan began his second term in office, UC was in the early years of its transformation from a municipal university to a state university.

"We were an ordinary institution," recalls Richard Friedman, senior assistant dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. "There was a sense of ordinariness. We had just become a state university in 1977, and we were doing a lot of catch-up. We thought of ourselves as more of a regional university than a national university."

At the same time, the university's enrollment figures were mimicking a downward trend in higher education across the country, says UC vice president of finance Dale McGirr, who was promoted by Steger shortly after he settled in as president.

"1984 was the beginning of the end of the baby boom or the sort of natural expansion process of enrollment," McGirr says. "It wasn't automatic anymore. We were coming to the end of that push in the '50s, '60s and '70s when you had either the GI Bill or the baby boom just pushing enrollment numbers like crazy."

Past Issues

Past Issues