A new reality

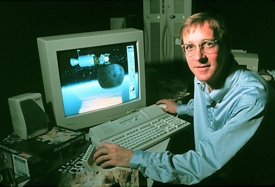

Technically, it was just one small step for man, but it was one giant leap for associate professor Benjamin Britton.

As he was stepping into the elevator of the launch pad at Kennedy Space Center, the historic significance began to overwhelm him. "This was the same elevator that carried the Apollo 11 astronauts," he says, getting more excited with each word. "It's that same aluminum elevator with funny little push buttons from the '60s, that same elevator that saw so many astronauts off on their way into space."

Illustration/Benjamin Britton

When the elevator stopped at the top, he marveled at the flame pit far below and shuddered at the cable that serves as a last-minute escape to the ground in case of an explosion. He was in awe. Out of the four years he has spent working with renowned scientists, engineers, astronauts, computer programmers, historians and artists from around the world, that one day was the most exciting.

It's all been part of the MOON Project, his major endeavor to commemorate the anniversary of mankind's first step onto the moon 30 summers ago, on July 20, 1969. Now, Britton wants the whole world to share his excitement -- but with more than one small step onto a launch pad. He's looking for people willing to take that giant leap to the surface of the moon.

The University of Cincinnati associate professor of electronic art is willing to take anyone to the moon's surface for a very reasonable price. In fact, he is offering a portion of the trip free.

To sweeten the package even more, travelers get a multitude of options at no additional charge: sitting in the driver's seat, working at Mission Control in Houston, watching from the White House with Richard Nixon, attending a New York party with Marilyn Monroe or standing in for Neil Armstrong taking that first giant leap.

It's the world of "mutual reality," a computer domain of 3-D animation and artificial intelligence, brought to life through the Internet so that people can actually interact with others. Britton and his team invented the mutual-reality technology and coined the term. Literally speaking, it's a step beyond virtual reality.

To experience virtual reality, one often dons a headpiece to view images that appear on a visor and relate to one's moves. Mutual reality, however, occurs among many individuals sitting at their own computers, located anywhere around the world. On-screen movements take place by using the computer's mouse, keypad or joystick.

The interaction among several people visiting the moon simultaneously is the exciting concept for Professor Benjamin Britton. "Mutual reality is not just a technology; it's a philosophy," he says.

"The term comes from the term 'multi-user virtual reality.' If you say that too fast, it comes out mutual reality. If you say it even faster, it comes out morality. It's about the connectedness between minds. That is what all our lives are about, mutual reality."

On July 20 [1999], access to the moon landing became available by downloading the browser for the MOON Project at www.moon.uc.edu. A faster performance with higher resolution will be available on a DVD-ROM (digital video disk), which can be viewed strictly on multimedia computers with an optical disk drive.

Only limited editions of the disk currently exist. By the end of the year, however, a full home-version DVD is due out with many more capabilities. Information on obtaining the disk will be on the Web site.

To offer the full DVD experience to those without the necessary hardware, Britton hopes to find museums willing to install computer work stations on which guests could share the mutual-reality environment with their global neighbors. "More museums are seeking capacities to exhibit work using electronic media," he explains. "I believe such presentations should focus on the art, not just the technology."

That's the true artist talking. Despite the cutting-edge technology Britton and his team have literally invented, he never lets anyone forget he is in it for the aesthetics.

"It's a spiritual quest for me," he says. "We find that with science you have something you can believe in, and with art, you have something you can feel passion about. When you put the two together, you can reach both hearts and minds. It becomes an interesting harmonic vibration."

The average person may not so readily identify with harmonic vibrations, but they will quickly appreciate both the visual images and the technology employed. Much of the art, created with animation and modeling software, closely resembles photographs. The pitted texture of the moon, in particular, is impressive.

"We wanted to make it as real as possible," Britton says, "to get away from computer graphics as much as possible and make it look like a video. We're doing this intensive technical development to give the viewers a sense that they exist in a virtual world." For dramatic effect, the team also added violins, percussion and a narrative.

By the July 20 anniversary, the core MOON project had been completed, yet additional features are being added through the remainder of the year. All the eventual components include the following:

- A historically accurate moon landing simulation: Through mutual reality, viewers can experience the lunar landing as it happened and even participate in it. They can choose to be Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin or Mike Collins, talking to Houston from the orbiter, operating controls in the lunar landing module as it starts its descent or walking around the landing site itself. To synchronize players around the world in an actual sequence of events, Britton has developed "artificial time" software. Making the simulation "as close to the real thing as possible" was his top priority for July 20. Visit the Apollo 11 Moon Landing Virtual Reality Simulation at http://www.moon.uc.edu/moonsim1.htm.

- A variety of mutual reality celebrations: Britton also planned an elaborate menu of characters and locations for viewers to select for participating in the historic event. All these options were not completed by July, but Britton is continuing to work on the project to make a more extensive MOON Project DVD commercially available. For that version, he is creating interactive situations featuring Jackie Onassis at a party, Andy Warhol in his apartment, Yoko Ono and John Lennon in Central Park, Jack Kennedy in heaven and the president in the White House, all of whom will view the landing on their "virtual" television sets.

- A scientifically accurate map of the moon: Compiled with data from the Air Force, a detailed map can be viewed on the DVD or downloaded off the Web site in different resolutions. Visit http://www.moon.uc.edu/vrmlmap1.htm.

- A 3-D virtual reality chat system: A chat room "virtually" takes place on the south pole of the moon -- at the International Moon Aerospace Museum in 3000 A.D. Role-playing games enable users to study historical artifacts and be teleported to a model of the landing site -- basically "a virtual reality recreation in virtual reality," Britton says with a chuckle. Troy Gerth, '86 DAAP graduate, helped to create the site, which received rave reviews from NASA, according to Britton. Eventually, the team hopes to have artificially intelligent museum docents guide guests, answering questions and showing them what they request. The site is available 24 hours a day at the www.moon.uc.edu or through the DVD.

- Feature-length documentary: Britton commissioned an internationally known, award-winning film producer and director, Aaron Ranen, to make an independent documentary about the moon landing.

Visit http://www.moon.uc.edu/cap1.htm.

While most computers will be capable of exploring the MOON Project Web site, only IBM-compatible PCs can join in the mutual-reality Moon Museum and the virtual-reality moon-landing simulation. Macintosh and SGI owners are limited to viewing a Quicktime movie and touring most virtual reality environments.

At this time, the only venue for viewing the documentary is the DVD and a digital video archive to be stored at University Libraries for researchers. Other opportunities to have it broadcast are still being explored.

If walking on the moon sounds a little too adventurous, how about watching the landing on TV at a party with Marilyn Monroe and Andy Warhol? Illustration/Benjamin Britton

The MOON Project's documentary's goal is to prove the landing really took place. For those surprised by that even being a question, Britton empathizes. He, too, was shocked to discover that 5 percent of the population believes the moon landing is a giant hoax.

After spending one year working full time on the project and shooting more than 50 hours of film, Aaron Ranen believes even more people than that have serious doubts. "You can't find telemetry data, and all kinds of hard data are missing," he says. "There are many reasons people would have wanted to create this fantasy. It leaves many doubts."

The film, of course, intends to dispel those doubts, historically, scientifically and in an entertaining manner. "I think you'll walk away with a new way of thinking about things," Ranen says.

Although discovering serious skeptics surprised Britton and Ranen at the onset, the project held a bigger shock: connections between America's space program and Nazi Germany, Britton says. The issues were serious enough to make Britton consider abandoning the project, but in the end, he and Ranen both decided not only to continue but to include their shocking findings in the final production.

Research included, in part, interviews with Buzz Aldren, three of the original scientists who worked on the team producing the rocket that took the United States to the moon, controllers working at Houston's Mission Control during the original flight, the last person to see the Apollo 11 crew on Earth (the man who closed the hatch on the space ship), the first person to see them return (the Navy frogman who first reached the floating capsule), Smithsonian Institute historians and Karl Sendler, the father of Doppler Radar.

As it turns out, morality has been one of the project's recurring themes. For the moon landing simulation, Britton and his UC team developed what he calls "virtual morality." Since their software would allow virtual people to carry out behaviors, the team had to determine what actions they would permit.

"People will be people," Britton says. "If we're building a world for them to be together in, it is upon us to structure the environment so it works well for many people. This is a pressing question for us as artists engaged in building software with scientists.

"We care a lot about the morality of a virtual person. When they come to our world, they will gather our values and beliefs. It's also a big responsibility because we're making software that will set an example."

Although the MOON Project's unveiling of the mutual-reality technology will undoubtedly bring Britton and his team accolades, it won't be the first for Britton. In 1995, he produced a critically acclaimed project that enabled people to wander through a high-resolution virtual reality model of the prehistorically painted Lascaux Cave in France. That work is still touring.

As soon as the cave project neared completion, Britton started scripting the MOON Project, later obtaining funds from the Ohio Board of Regents. In '97, when a national trade publication featured his project, work accelerated to a frantic pace, and it has remained so.

From the beginning, the project has meant more to him than simply science or art. "I want to demonstrate my belief that technology can solve many problems," he says, "to show how the sense of accomplishment of society can create a time of optimism. The moon landing experience expresses all of that.

"I look forward to a time in the future when people will also share these elements of our cultural legacy and think about the first landing on the moon then, as we do now."

'Dirty little secret' haunts Britton

Benjamin Britton

"In the tunnels of the rocket factory, five people a day were hung in front of other workers to discourage slacking and sabotage," says associate professor Ben Britton -- so quietly and reverently that he nearly whispers it. The image still haunts him.

"This is information that has simply never been released to the public before," Britton says. In researching the space race, Britton had stumbled upon some obscure history.

Many of the rocket scientists who created the Saturn V rocket, which propelled America to the moon, had come from Germany, where the men had developed the V-2 rocket that was dropped on Britain during World War II. They had been working for the Nazi government in the secret, underground Mittelwerk rocket factory.

Some history buffs know that much, but Britton says the shocking discovery was that the plant had been run by "slaves," who were routinely executed. "And at the end of the war, the Nazis killed all 10,000 of them," he says.

The only ones to escape the Nazi annihilation were more than 100 rocket scientists led by the V-2 principal developer Wernher von Braun. The group surrendered to the Americans, bringing much of their military expertise with them. From there, von Braun and his team became the nucleus of the NASA space program, and von Braun was named the first director of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center.

Suddenly, Britton realized that his vision of the moon landing as a "wonderful example of human manifestation" had a history of research conducted at the expense of others. Overwhelmed with "dismay about the horrible things that people can do to each other," he considered quitting the MOON Project.

"It's been a hard discipline for me as an artist to reconcile," he says. "We wanted the piece to have a spirit of celebration and appreciation, yet there's this dirty little secret -- five people a day murdered in the tunnels."

In the end, he decided the project's documentary would include interviews with camp scientists and a survivor. "We wanted to look at the truth without closing our eyes," he says. "If we continue to hide the truth, we injure each other.

"Healing can happen when we share. We want to understand what it means to be human, that this world is not black and white. Working together to accomplish things that are constructive and focusing on those things will give us reason to be glad and celebrate . . . now and in the future."

Links:

Center for the Electronic Reconstruction of Historical and Archaeological Sites

For interesting links to other space information, visit MOON Warp Links and MOON Space Stuff

Benjamin Britton's profile (2000)

Past Issues

Past Issues