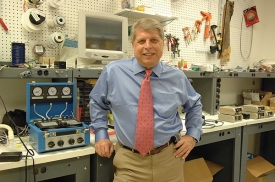

Dr. Bill Wiesmann, A&S '68, HonDoc'08

Bill Wiesmann's advances have transformed medicine both on the battlefield and in civilian trauma centers. In 2004, the military named the University of Cincinnati grad's 4-by-4-inch HemCon bandage one of the year's "Top 10 Greatest Inventions" for its ability to stop seriously wounded soldiers from bleeding to death. Today, the revolutionary bandage is available to U.S. soldiers around the world and is commonly stocked by civilian medics nationwide.

Since the early days of warfare, soldiers have died from bleeding. We had been looking for years for a solution to that problem. We knew that if we could develop something that would stop bleeding, or slow it down and give doctors enough time to get a patient to the hospital for surgical care, we could save lives. When 9/11 occurred, we got accelerated funding to get this product to the marketplace.

We sort of accidentally discovered this bandage in looking at a lot of different things. We tried making very crude bandages out of ground-up shrimp-shell material, and it seemed to work. Then, we carried it a little further and made even more sophisticated bandages. Those worked even better, and so on and so on. Now there are a lot of different companies that make bandages to stop bleeding, in addition to ours. And together, all of these products have led to a great reduction in loss of life from combat injury.

Don't ignore anything. Sometimes the answer is obvious. You just don't see it. You have to be able to ask the right questions and look for the solutions that are already in front of you. This original shrimp-shell observation was from a Chinese discovery that has probably been known for hundreds of years. It was just ignored.

Ironically, I had spent my whole medical career trying to avoid the military but ended up very much involved in things that affect life and death on the battlefield. The military gave me an amazing opportunity to do things that you normally wouldn't think about doing in civilian medicine. It forced me to think about medicine in a very different way.

We use this idea of "over-the-horizon thinking" a lot. You think, "What is that next great thing?" Then you imagine that you are over the horizon, and you have this thing in your hand. You look back and try to determine what kind of things I have to do in order to break through bottlenecks to get there. That way you can break down the problem into solvable sets. You have to know where you want to be at the end of the day in order to start your day.

I became sort of an expert in all different fields of medicine. If there is a take-home lesson, it is not to drill down into such a high degree of specificity that you miss the big picture. In fact, most of the time the answers are in looking at what I would call an integrative or systems approach to a problem. Realize that everything is connected.

Keep your eyes open to everything possibly related to the field that you are interested in. Quite honestly, the undergraduate education I got at the University of Cincinnati really prepared me for that. I took courses in everything from anthropology to economics to languages to chemistry and biology. It gave me a really broad breadth and basis to become a medical scientist and a medical doctor. I got an outstanding education not only in the sciences but also in the humanities and liberal arts.

I stuck to it like a bird dog. I had a belief early in my life that I wanted to be a physician and a scientist. If you have a passion like that in life, then you had better follow it because that is what you are going to do well. That's what you are going to succeed at, and that's where you are going to add to society.

My passion as a physician has to do with who I am in terms of wanting to help people. In my family, the physician was always kind of considered the highest person in society. My mother admired the physicians she knew. So I always thought that would be a great thing.

The fact that I could only take care of one patient at a time was one of the things I didn't like about going into practice. Whereas, I could potentially help a lot of people by doing research. You go into medicine with the idea of trying to save people. A lot of the things that I've done -- and I've worked with some really great people to develop new products -- will affect the lives of thousands of people ultimately, which is very rewarding as a physician.

The greatest thing that you can do as a medical scientist is to develop something and see it into the hands of the doctors, nurses and lifesavers to help people. That's the ultimate thing.

Wiesmann retired in 1997 as director for combat casualty care for the U.S. Army at Fort Detrick. He earned his undergraduate degree in chemistry from UC and his medical degree from Washington University in St. Louis. Backed by millions in research funding, the one-time senior scientist at the Walter Reed Institute of Research founded multiple biotech companies, collectively called the BioSTAR Group.

Among his many career experiences, he has directed research for NASA in which he designed multiple experiments that have flown on space shuttle missions. He also holds 34 awarded or pending patents from his work in biosensors, automated diagnostic devices and advanced tissue engineering.

His latest passion involves finding new uses for medical-grade chitosan-- the same shrimp-shell material he chemically processed to stop bleeding in the hemorrhage-control bandages -- to prevent and kill drug-resistant organisms, including the bacteria that commonly cause staph infections, known to kill thousands of people every year.

Link

Read about other UC inventors

See complete list of UC's honorary degree recipients

Issue Archive

Issue Archive