Aiming higher

Snowballs, rocks, sticks. You name it, she could chuck it. By age 7, Susan Seaton had an unnatural ability to whiz objects for distance and with deadly accuracy and had caught the attention of her East German government. At an age when American girls were playing jacks or hopscotch, young Susan was already enrolled at a government-run Olympic training center two days a week.

By 10, she trained five days a week and was winning neighborhood bets that she could out-throw even the older boys near Saalfeld, Germany, not far from the Berlin Wall. "We had these five-story block buildings that were always in Eastern Bloc countries," recalls Seaton, UC's women's track coach. "My friends would challenge these guys that they couldn't throw a snowball on top and that I could.

"Sometimes there would be a little money or candy on the line. It was real fun to pretend I couldn't throw it up there at first. Then I'd inch my way up, to lots of screaming and yelling, before throwing a couple on top."

Communist sports school

At age 14, Seaton left home to join a government-sponsored sports school 40 minutes away with hopes of furthering her javelin-throwing prowess and ultimately becoming a world-class athlete.

"You were selected, based on your athletic abilities, to go there and train with better coaches and better facilities," she says. "By then, I could throw a 300-gram ball (two-thirds of a pound) the length of a football field."

Seaton's hopes of representing her country competitively fizzled within a couple of years when she lost her place in the sports school following knee injuries and had to return home.

"Now that I'm a coach, I can look back at the human performance indicators,

and I can see that we were overtrained," she says. "It was really just too much for our young bodies."

Losing her status at the sports school was a painful lesson for Seaton, who was also now questioning her country's social policies. But challenging the status quo, it seems, was an inherited trait.

Seaton's father, a machinist, and her mother, a school teacher, had at one time refused to join the Socialist Party, not so much because they opposed socialism but rather they thought the party failed to live up to its ideals. She recalls one year when they attempted to abstain from voting.

"They felt it was pointless because there was really only one party to vote

for," she says. "So they decided to just stay home."

The Stasi, or state security, had other plans and stopped at their home several times questioning why they hadn't voted.

"There wasn't any force involved," she says. "But it was sort of pointed out that it wouldn't be good for their future in their jobs if they didn't participate. They were eventually escorted to the polls to vote."

Though much has changed about her life since spending her childhood and adolescent years hemmed in by the Berlin Wall, Seaton's knack for confronting the state of things remains intact.

Not long after taking over the women's track and field program, she took stock of her rather uninspired team and decided the problem wasn't the talent level but rather their level of expectations.

It was the summer of 2010, and the Bearcats were a team who had plenty of individual successes but few real team accomplishments. Their new head coach, a woman with a heavy German accent and many years of assistant experience, was convinced they had stopped taking themselves seriously.

In other words, it was time for a gut check. "We were satisfied with being mediocre," Seaton says. "It was a big hurdle to get over."

Attitude adjustments

By the end of the 2011 season, the team had not only bought into their coach's culture shift, they turned in the best season in team history as UC moved from a 12th-place Big East finish to sixth in the conference, including several who qualified for nationals.

Seaton's journey to Cincinnati

|

"We almost feel like we achieved more than we possibly could have thought you could do in one year," says Seaton. "But at the same time we are aware that we can do even better. There is now a lot of excitement within the team to see what we can do next year."

Seaton is astounded by the shift in her team's attitude, and she credits it back to the simple challenge now repeated not just by coaches but by the athletes of one another: "Is this really the best you have to offer?"

For the coach, that question defined much of her life, particularly in her socialist upbringing, where items such as cars, chewing gum, designer sneakers or even basic building materials were next to impossible to attain.

"You made deals and bartered," she says. "That was the only way you could get things. You couldn't just go and buy any record. We would make copies of music from the radio for each other. You could only get it if people shared."

Far beyond the joy of scoring a taped copy of Prince, Bryan Adams or Depeche Mode, Seaton remembers the day she was accepted into the German College of Sports Science. Though only a handful from the entire country would be taken, she refused to list a second college choice and risked getting shut out of school altogether. She would eventually become class president.

Piece of the wall

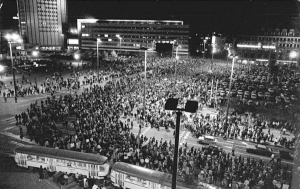

During her freshman year in the fall of 1989, she and a group of friends were in Leipzig during the first Montagsdemonstrationen or Monday demonstrations, in which hundreds of thousands took to the streets to protest the Communist regime.

"We were in this ice cream parlor, and the next thing you know there was a battle scene outside the window," she says. "There was a street fight going on with Molotov cocktails flying off the roofs of houses and people throwing rocks and sticks.

"The Secret Service got involved. They were all wearing long black leather coats, and they linked arms and tried to march down the street and push people out of the center of the city.

"People came in bloodied from being hit by rocks. They were screaming. It was pretty crazy."

Similar calls for freedom across the country, though mostly peaceful, eventually led to the fall of the Berlin Wall in November of that year. Seaton and her friends responded by piling into trains headed for Berlin.

"It wasn't so much that we wanted to leave our country," she explains. "We just wanted change.

"You were searching for answers. In a sense, your whole belief system you had growing up with had fallen into a shambles.

"We just embraced it. We went with it. We all got our little piece of the wall."

Link:

More about UC's track program

Past Issues

Past Issues