Modest man of honor nearly overlooked

by Greg Hand, A&S ’74

The old man arrived at the University of Cincinnati early in the afternoon of Saturday, June 20, 1903.

The campus was crowded with newly minted graduates, still clad in mortarboards and gowns from the morning commencement festivities and mingling with underclass students, while local dignitaries prepared for a big afternoon dedication ceremony that would feature speeches from Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson and first assistant Secretary of State Frank Loomis.

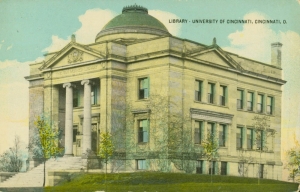

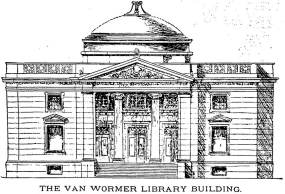

The university would soon officially dedicate four new facilities — Cunningham Hall (the wing attached to the southern end of McMicken Hall), Van Wormer Library, the Technical and Engineering Hall and the Athletic Field. For Cincinnati, it was an “A-list” event.

A huge tent occupied the lawn between Cunningham Hall and the Van Wormer Library, sporting flags of the United States and Cincinnati, as well as red and black banners. The tent was empty when the old man arrived and would only fill when a procession, boasting all the pomp and regalia the young university could muster, wound its way down Clifton Avenue and up the hill onto the campus.

The elderly gentleman climbed the steps up to the stage and sat down to catch his breath, several rows back from the lectern. A young man, charged with guarding the stage seating, approached and directed the solitary guest off the stage back to the last row, at the very edge of the tent. Although the day was pleasant, there was a good breeze, and the tent flaps banged gently against the old man as he sat there — now in shade, now in sun, now in shade … .

As the dedication parade arrived, the frail man in the back rose a little from his chair to behold the academics in all their be-robed opulence, the fresh-faced co-eds in their spring finery and the husky young men still chanting their class yells while Herman Bellstedt’s orchestra performed a coronation march.

The ceremony began a little late. It was 3 p.m. before UC board chairman Frank Jones called the assembly to order and Rabbi David Phillipson, HonDoc ’32, recited the invocation. Secretary Wilson spoke extemporaneously to the delight of the standing-room-only crowd.

Judge Rufus Smith made the official presentation of Cunningham Hall on behalf of his friend and banker Briggs Cunningham, who had funded its construction. Judge John Sayler then rose to present the Van Wormer Library building. As the judge approached the lectern, one of the university trustees, Samuel Trost, rose to call for a brief pause.

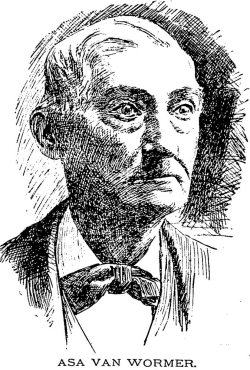

Trost, a wealthy cigar-box manufacturer, had grown up on Seventh Street and knew very well the butter-and-egg merchant from next door. He saw the 85-year-old man whom he called “Uncle Asa” sitting at the very back of the tent and brought him arm-in-arm to a chair at the front of the stage.

Perhaps it was his worn suit that distracted attention. Perhaps it was a rumor that he had taken ill and would miss the ceremony. Perhaps it was his seat at the periphery of the event. Whatever the reason, no one had noticed Asa Van Wormer, the donor whose generosity had paid for the new library being dedicated that day.

Thunderous applause greeted this discovery, and the cheering crowd demanded Van Wormer speak. Led to the lectern, he waved his arm up and down and announced, “That’s all I can do.”

He returned to his seat, but told the man next to him, “This is the best time I have ever had.”

It is fitting that Cunningham Hall was dedicated on the same day as Van Wormer’s magnificent library, for the two men inspired each other to make their gifts. In the late 1890s, soon after UC had moved up the hill from the Charles McMicken estate on lower Clifton Avenue to its present campus, a delegation traveled out to Asa Van Wormer’s place on Winton Road. The new McMicken Hall had a north wing, the gift of Henry Hanna, who built a fortune in coal and real estate, and the directors sought a donor for the proposed south wing.

Cunningham, a banker, suggested that Asa Van Wormer was their man. Van Wormer had retired in 1885 to a small farm, but remained an active investor in stocks and real estate. He had assembled his fortune as a successful merchant selling butter, milk and eggs to markets in New Orleans. It was estimated his estate would be worth about $500,000.

The trustees made their pitch, and Van Wormer agreed to add a codicil to his will, providing for a south wing. Cunningham asked if Van Wormer wouldn’t donate the money right then, instead of waiting for his inevitable demise.

“I don’t wish to deprive you of that pleasure,” Van Wormer said. “You should build that building, Mr. Cunningham, and you will have no idea how you’ll enjoy seeing it go up.”

Still, Van Wormer modified his will, and left on a trip to California. He returned to discover that Cunningham had met his challenge and paid for the south wing.

Van Wormer contacted the university trustees and announced in 1898 that he would provide 1,000 shares of stock in the Cincinnati Street Railway Co. to fund a library for the University of Cincinnati.

He specified that the gift was made in memory of his wife, Julia, who had died the year before. The gift amounted to approximately $50,000 and didn’t quite cover the total cost of building and furnishing the library, but Van Wormer stepped up to cover the overrun.

On his death in 1909, at the age of 91, Van Wormer was buried in Spring Grove. The university’s Board of Directors voted to drape the library building in mourning for 30 days in his memory.

Greg Hand is the associate vice president for University Communications.

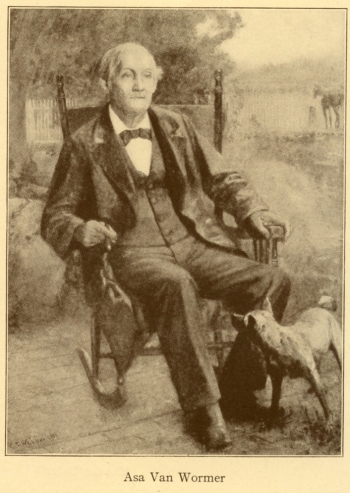

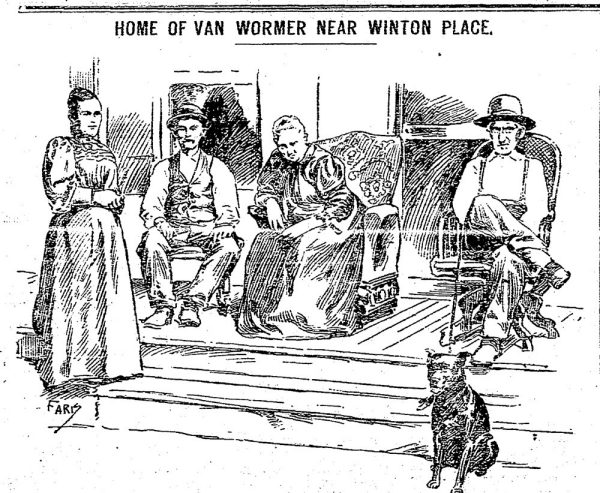

CINCINNATI POST (1903) — Scene at the home of Asa Van Wormer on Winton Road, near Winton Place [renamed Spring Grove Village in 2007]. It is from the last picture taken of Mrs. Van Wormer (center), in whose memory the new library is a present to the University. Asa Van Wormer is the man on the right. The other man is a nephew, William Van Wormer, and the woman standing on the left is Mrs. l. E. Sellers, the housekeeper. Just below Asa Van Wormer is his dog Pete, a black mongrel, who was poisoned and died shortly before Mrs. Van Wormer. He lies buried in a dog graveyard on the Van Wormer place in which about 20 other deceased canines keep him company, each dog having its own little tombstone. Van Wormer is a great lover of all animals. He had a white pacing horse named Clay Washington with which he used to beat all the other gentlemen of his day in the daily “brushes” on Spring Grove Avenue. [Chester Park, a horse track and amusement park, thrived on Spring Grove Avenue from 1891 to 1932.]

Past Issues

Past Issues