Geologist's career takes him to top of the world and beyond

50th anniversary of Barry Bishop's historic achievement

Fifty years ago, alumnus Barry Bishop scaled Mount Everest as part of the first American team to successfully summit the world's highest peak. The 1954 A&S grad and National Geographic photographer reached the top on May 22, 1963.

To honor the anniversary of that historic event, we are republishing a feature article on Bishop, which the university magazine originally ran in January 1991.

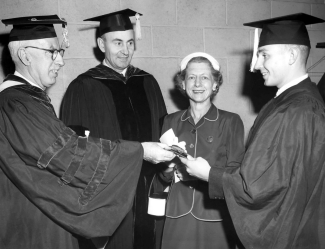

Three years later, 1994 was an eventful year for Bishop. First he retired. Then in June, he was UC's commencement speaker and received an honorary degree.

Only three months later, in September, the 62-year-old adventurer, who had repeatedly defied death in the field, met his untimely end in a car accident. In Idaho. On his way to deliver a lecture in San Francisco.

I felt that it was such a meritless ending for a man who had survived falls from cliffs, entrapment in oxygen-starved environments and an overnight bivouac in temperatures of 18 degrees below zero.

I also felt honored to have spent some time with the down-to-earth legend in 1990, when he came to campus to receive the Distinguished Alumni Award from the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences. Even today, I can still recall his energy, enthusiasm and excitement for life.

— D. Rieselman

See photo galley below. Click on any image

to enlarge it and launch photo gallery.

Original 1991 article

'No pain, no gain' part of the reality of climbing to the top

by Deborah Rieselman

Five miles above sea level, huddled in the pitch dark of a moonless night with no oxygen tanks, shelter nor flashlights, Barry Bishop and three other men gave thanks. The wind gusts of 60 to 70 mph had died down, and the temperature had leveled off to a mere 18 degrees below zero. Their oxygen-starved lungs ached; their fingers and toes were too frozen to feel, and their hemorrhaging eyes yielded blurred vision. But if the gusts had continued, the men would have surely perished during the five and a half hours they spent waiting for the sun, which would guide them down the summit of Mount Everest.

Bishop lost toes and parts of fingers to frostbite, but by successfully conquering the world’s highest peak in 1963, he also conquered the threefold dream of his childhood. “As a kid,” says the UC geology alumnus, “I had three dreams: going off to Antarctica with Admiral Byrd, working for National Geographic and climbing Mount Everest. All three came true. I was pretty lucky.”

Bishop attributes his success to being in the right place at the right time. Others say he is a talented man who has worked hard to earn every accolade he has received.

The hard work seems evident. "In November of '55, I turned in my master's thesis on a Tuesday, defended it on a Thursday, had rehearsal dinner on Friday, got married on Saturday, had a three-day honeymoon and reported for active duty the first week in December," he recalls. He was shortly in Antarctica as a scientific adviser to Rear Admiral Richard Byrd's staff.

Years later as a member of the first American expedition to scale Mount Everest, he recovered from falling off a ledge at 28,500 feet and miraculously escaped a fire that consumed his face mask. Eight years after that, in conducting field research for his doctoral dissertation, he spent 15 months hiking 2,000 miles with his wife, 3-year-old daughter and 21-month-old son through the most remote area of Nepal. The family bathed in irrigation ditches, and Bishop sewed up the kids' gashes and set his wife's broken bone.

More time in D.C. today

Today, he spends more hours as a Washington, D.C., bureaucrat than he would like. As chairman of the National Geographic Society's Committee for Research and Exploration, Bishop oversees the awarding of nearly $4 million in grants to 200 to 300 research proposals annually. His pace, evidently, has not slowed. "My days are peripatetic," he says. His weekends and evenings are not much better.

Despite the paper shuffle and lack of time for vacations, he loves his job. "I've been at National Geographic for 31 years. I never dreamed I'd be head of the research committee. It's one of the great jobs at Geographic. It's a wonderful challenge and needed work. It's also high powered -- everything in Washington is high powered -- so there is a lot of stress. But the committee and staff are full of wonderful people."

Still, it's ironic that Bishop got into geology to enjoy the outdoors and now spends most of his time indoors. Friends say he is happiest in the field. "Geology made it possible for him to combine his hobby with a career," says long-time friend Richard Durrell, the UC geology professor emeritus who, Bishop says, "turned me on to geology."

"He's great at fundraising," adds Durrell, "but I think he's an explorer at heart."

"Wanderlust" is what Bishop calls it. "I guess a bug bit me at an early age. I was really intrigued, always wanting to see what lies over the next ridge."

His father, Robert Bishop, UC dean of men from 1946-61 and executive secretary of the University YMCA in Clifton at the time, had a lot to do with it. "Dad's roots were in western North Carolina. When I was a small child, we would go back to see his relatives -- in the shadow of the Smokies.

"At age 4, I partly climbed on my own, but was mostly carried on my father's back, up Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak east of the Mississippi. Then, when I was 8, we began spending summers at the YMCA conference camp at the Rocky Mountain National Park.

"That first summer in 1940, I went on a lot of ranger-led environmental hikes for kids." It was love at first hike: "the flora, the fauna, the geology, the challenge of getting from A to B in the mountains," the Cincinnati native says.

By the time Bishop was 12, he wanted to learn technical climbing, but World War II had shipped out all the experienced climbers. "So my buddies and I began to teach ourselves with a jute rope in one hand and Henderson's 'Handbook of American Mountains' in the other. We would do such things as shorten our mothers' lives by bringing them out to a cliff to watch us do a 100-foot rappel on a jute rope."

A few years later, the 10th Mountain Division returned Stateside, and Bishop's lessons came from battle veterans who put up with no nonsense. "I had such good tutorial that when I was 15 I started guiding myself all over Colorado and Wyoming."

Upon high school graduation, Bishop selected a college based largely upon his extracurricular interests. Although his father was still a UC dean then, Barry headed for Dartmouth because it had mountaineering and ski clubs. During his freshman year, he took a geology course and realized it was a course worth pursuing.

As luck would have it, his hometown had a much better geology department than Dartmouth's, so he transferred to UC with a declared major in geology. Here he met Durrell and was hooked.

Freshman tackles Mt. McKinley

Of course, the lack of a local mountaineering club did not squelch his hobby. During the summer of '51, he joined an expedition to Mount McKinley, the highest peak in North America. Assisting well-known researchers Mel Griffiths and Bradford Washburn, he made the first ascent of the mountain by the West Buttress route. He also achieved something of greater importance than he realized: he was making contacts and building a reputation for himself.

To help fund the trip, Bishop took pictures, sold them to the "Cincinnati Post" and got them nationally syndicated. He also lectured at local women's clubs afterwards, but found himself so besieged with requests that he decided to price himself out of business. "I started to charge $75 a lecture," he laughs, "thinking that would put a stop to them. Instead they increased. I made enough money to handle all my operations at UC the next year and had enough left over to go to Europe the following summer.

"Photography, lecturing, writing and amateur journalism ended up sustaining my rather expensive hobby.”

On campus, the Cincinnati mountaineer was definitely an oddity and was gaining a reputation as something of a character as well. "Even though my dad was dean of men, I did my own thing," he recalls.

That reputation almost worked against him when he met his future wife, Lila. "I met her standing in a bursar's line. I tried to get a date with her, but she couldn't stand me. Her sorority sisters had told her, 'Don't have anything to do with that Bishop. He is really wild.’” It took eight weeks, but she finally relented to his persistent invitations.

The couple was courting and climbing together, when Bishop graduated in '54. He was named Ivy Day orator and the McKibben Medal recipient, selected by the A&S faculty as "outstanding graduate of the college."

As an ROTC student, he planned to report directly to the Air Force after graduation, but received an offer to participate in a research project in Greenland. Griffiths, whom he met on McKinley, had recommended him. The Air Force granted him an 18-month delay, and he quickly applied to the master's program at Northwestern University, because of its proximity to the Army Corps of Engineers' Snow, Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment. He was accepted.

Pushing his 18-month delay to the limit, he finished his thesis and got married just in time to report for active duty in December '55. Within six months, someone from Admiral Byrd's staff had tracked him down. "It was the damnedest thing," he says. "This man, who was a geographer with a PhD, had read my master's thesis and somehow knew I was in the Air Force. He said they had an opening for a scientific adviser on the staff.

"Almost immediately, I was named by Eisenhower as the U.S. scientific observer attached to the Argentinean government's Antarctic research. I visited all the Chilean, Argentine and FIDS (Falkland Islands Dependency Survey) bases, and some of the old American bases. I met the Duke of Edinburgh down there. For a punk kid, it was pretty heady stuff."

It was also part one of that lofty childhood dream. More important, part two of Bishop's vision was beginning to take shape.

Joining National Geographic

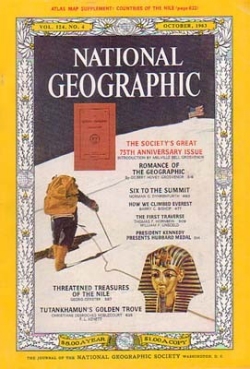

During his Antarctic assignment, some of Bishop's photography got picked up by National Geographic. After completing active duty, he joined Geographic as a picture editor. Part two was now fulfilled.

From picture editor, he became a photographer. He recalls one special assignment in Texas: "I came into the Holiday Inn tired from being in irrigation ditches covering the harvest. I was one unhappy camper. All I wanted was a hot bath and bed, when the phone rang. The voice on the other end said, 'Hello, this is Sir Edmund Hillary.' (Hillary was the first person to reach the top of Mt. Everest, in 1953.) I said, 'Great, you've just reached Sir Winston Churchill.'

"But it was Hillary. He had been given my name by the American Alpine Club and wanted to discuss an expedition in the Himalayas." Furthermore, he was willing to give Lila, who was an experienced climber, the job of transportation officer, so she could accompany her husband.

Bishop was thrilled, but Geographic "couldn't have cared less," he says. So he took a 20-month leave of absence without pay to satisfy his wanderlust once again.

On that expedition, he reached the 22,494-foot summit of the previously unclimbed Mt. Ama Dablam. The difficult ascent heightened his reputation.

Subsequently, his impressive academic and professional vita led to an invitation to join the Mt. Everest expedition. Not only did the opportunity represent part three of his childhood dream, but it would enable him to indulge his fascination with the way people cope with limited resources at high altitudes.

He obviously accepted. This time, National Geographic shared his interest.

Ready to take on Everest

"The makeup of the expedition was in place by December '61. Each of us had jobs to do. I was in charge of still photography, tents and a lot of fund-raising."

To try out equipment and get used to working together, the expedition had a trial run on Mt. Rainier, Wash., in September '62. The actual Everest ascent began in February '63 when 19 expedition members started a 185-mile hike across the Himalayan foothills to Everest. Accompanying them were more than 900 porters, 32 Sherpas and 27 tons of supplies -- a human baggage train stretching four miles in length.

Upon reaching the mountain, the team set up a series of camps, each one a day apart. A certain number of people remained at each site, leaving only three two-man teams of climbers at the final camp. Tragedies along the way included the collapse of a chain bridge across a mountain gorge, a minor epidemic of smallpox and the death of one expedition member when an ice wall collapsed.

Bishop and Lute Jerstad were the second team to reach the 29,028-foot peak. Bishop's subsequent article in National Geographic detailed the claustrophobia, nausea, "muddled sense" of balance and weird mental effects he suffered from insufficient oxygen during the climb. Although he used bottled oxygen, the canisters' weight limited the number he could carry. Forced to conserve what little oxygen they had, the two breathed as low as one quarter the recommended level. Eventually the oxygen ran out, and both had to survive on the atmosphere, only two-fifths the oxygen density of sea level.

The morning of the ascent to the highest point on earth, he overcame a fire in his tent and recovered from slipping off a ledge. Since insufficient oxygen made movement agonizing, each step required seven breaths. Once on the top, he and Jerstad "cried like babies," wrote Bishop in Geographic, "with joy for having scaled the mightiest of mountains, with relief that the long torture of the climb had ended."

Unfortunately, the torture had not really ended. Darkness enveloped the two before they could make it back to the last camp. Furthermore, the third two-man team was two hours behind them, ascending the summit from a different route. That team was having trouble finding its way down along Bishop's route, so Bishop and Jerstad stayed put to guide the other pair with their voices.

Shortly after midnight, the four faced the realization that they could not continue their dangerous descent in the dark. They spent the remainder of the night camping at an altitude 2,000 feet higher than any previous bivouac in history.

As Bishop pointed out in one Geographic account, "We had been lucky that season: Everest had been uncommonly tranquil. In short, the weather had been only miserable, not impossible."

In looking back, Bishop does not dwell on the pain. "As far as undergoing discomfort, you just take that for granted. Above 8,000 meters, you go into a different world. It was never-never land. You move and think in slow motion. The magnitude of discomfort increases, but you don't think about it anymore. You just pay close attention to deterioration due to the lack of oxygen and close attention to where avalanches come down. You only concentrate on trying to get the job done."

His favorite memory comes from the camaraderie. "We basically all got along very well together," he says. "We all believed the team came first. Although we didn't know each other before Rainier, we went out friends and came back even closer friends. In light of the factors of stress, that is the mark of a great expedition."

It is also the mark of Bishop's priorities. Professor Durrell points out, "Barry has grown closer to geography than geology." The human aspects of his experiences are of great importance.

After Mount Everest

After Everest, Bishop knew he wanted to pursue a doctorate in cultural ecology -- as he explains it, "paying attention to climate, weather, soils, geomorphology on the physical side; and social institutions, livelihood pursuits, division of labor on the human side." His focus? How inhabitants of varied, forbidding regions of the Himalayas manage to stay alive.

Once again, he took a leave of absence from the society. He completed the doctoral program at the University of Chicago in a year and decided to do his dissertation field research with his family in the Karnali Zone of western Nepal. With 12,000 pounds of food, the Bishop clan joined an 11-man team for 15 months in Nepal's largest and most isolated zone. Ten of those months were spent on the trail, covering 2,000 miles on foot.

Before leaving, one of Bishop's biggest concerns was his ability to handle medical emergencies. "Two of three kids there die before the age of 4," he relates. "A colleague of mine lost a child within a week in central Nepal. So I did some specific medical preparation to feel fairly good about diagnosis. I wanted enough self-confidence that I wouldn't hesitate to take drastic action if the situation called for it.

"In the end, the only skill I really needed was the occasional use of sutures. The kids were always getting cut and needing a few stitches. I also had sick call every day and ministered to the people around the area. I set a lot of breaks."

Brent was 21 months old and Tara 3 1/2 when the Bishops left the States. When they returned, they were 4 and 6. In the interim, the children learned a lot.

"Tara's Nepali ended up as good as her English," says Bishop. She would draw and sing in Nepali.

"Brent became the mascot of the staff. He was often found in the kitchen with the cook's son. He came out with a vocabulary of 200 to 300 words from every country the Sherpas had ever been to -- the filthiest vocabulary you ever heard," chuckles dad.

"Those were the best years of our lives. We were in a totally nonmaterialistic lifestyle. In western Nepal, you come close to birth, life and death all the time. After experiences like that, your rank order of values comes back to the basics.

"My overall lasting memory is an experience of such intense and interwoven family intimacy that it really put facets of life in a good, healthy order. It was very special."

So special, in fact, that the four had a 300-mile "reunion" trek in Karnali in '87. "We spent 27 days on the trail," he fondly remembers, "and had all the thrills, spills and emergencies that we wouldn't want if we were leading clients. Flood waters, for instance, pushed us into the China border."

That was the last time Bishop could get away from work long enough to take a lengthy trek. This fall, however, he and his wife, Lila, plan to co-lead a trek in the same area.

His hectic schedule similarly kept him from publishing his Ph.D. dissertation until this fall. Regardless of the delay, his book, "Karnali Under Stress," has received good reviews.

Taking aggressive initiatives

One reason his work at the society is keeping him busier than ever is a new focus that the committee has taken. "As we enter the new decade, we have some priority interests and for the first time will take some initiatives in soliciting grant proposals on specific research problems," Bishop explains. "In the past we were reactive. Now we're taking aggressive initiatives as well."

It all started in 1988 when Bishop planned and coordinated a week-long symposium, sponsored by the research committee, which brought in 20 distinguished scientists from around the world to address global concerns. From that came the idea to launch major multidisciplined research initiatives on critical problems facing humankind. Last fall, the committee began its first "initiative" -- dealing with water.

"The quality, quantity and availability of potable, uncontaminated fresh water on Earth is a concern that will make the energy situation look like nothing," Bishop stresses. "We could live without fuel for cars and transportation, but we can't live without water.

"We have a multidisciplined theme: human interaction with water, exploration of water, coping with water problems and contamination of water. Once we have a precise design, we'll begin to raise funds. My five-year plan is to get the initiative from the planning stage to the operational stage with research parties and funders. After that, I may retire."

Retire?

"Well, lead treks and continue research and maybe teach some courses."

Whatever his decision, he will surely find a way to work in a generous dose of adventure. Those who know him best admire not only his scientific contributions to the geographic profession but his approach to life.

One such admirer is Jack Ives, professor and chairman of the Department of Geography at the University of California, Davis, and president of the International Mountain Society. He speaks of Bishop's "professional impeccability, commitment to excellence, courage and love of the mountains." He also describes him as "mischievous, full of joy and candor, as adventuresome as ever."

To prove his point, Ives relates his first recollection of Bishop: "We were together in Swedish Lapland as participants in a field symposium on glacial geomorphology. The field trips were arduous, and the weather was unusually warm. We had a very long day and after a long walk were due to catch the train to return to Abisko.

"Barry decided to take an equally long route over another pass and across the mountains, but running. After all, it was 1960 and he was training for the ascent of Everest. There was much laughter as he caught up with us at the Abisko tourist station and leapt into the sauna with us far-less-travelled, but still-tired geomorphologists.

"From my point of view, he is a cornerstone of our profession. In a day when our heroes almost all seem to have feet of clay, we have a few who stand out as pillars that hold up the temple. Barry is one of those."

Update from a Beta Theta Pi

Two UC pledge brothers reunited after death

When Bishop died, his cremains were buried in a shrine in the Tengboche monastery in the Khumbu region of Everest, an area that Bishop had frequented, lived in and loved. He had been to the monastery numerous times while on the way to climb the mountain, photograph the people in the area and do research.

In planning one of his follow-up Everest expeditions, Bishop had turned to an old Beta Theta Pi brother from UC, Dr. Walter "Clare" Reesey, A&S '53, MD '57. The story came to UC Magazine through UC Foundation trustee Elroy Bourgraf, Bus '54, a fellow Beta brother:

"Bishop solicited his old friend Dr. Clare Reesey, who by then was a very successful family-practice doctor in Youngstown, Ohio, to accompany one trek to base camp on Everest for medical support. This experience further bonded their brotherhood and enhanced their mutual respect."

Reesey passed away in 2012, nearly 18 years after Bishop's death in 1994. But the time had not reduced the doctor's longing to be with his old friend. It turns out that he had requested that some of his ashes be entombed in Barry's "chorten" at the monastery.

"So Barry's son Brent took his ashes in a clay teapot, made by Clare's grandchildren, back to Everest in May of 2012," Bourgraf recalls. "Hence their friendship and brotherhood will last an eternity."

Past Issues

Past Issues