Stories of segregation, slander and secularization

by Deborah Rieselman

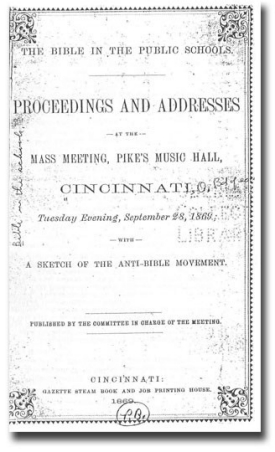

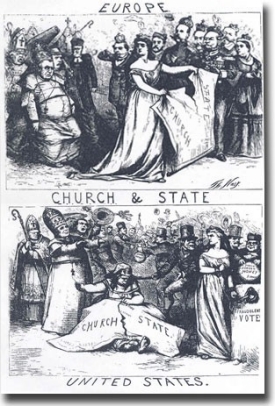

As the Catholic-Protestant animosity in Cincinnati grew increasingly hot, words like "infidel," "exclusionists" and "intolerant" began spewing out of mouths. One September evening in 1869, a "mob spirit," as local newspapers described it, reached the boiling point.

Hundreds of citizens crowded inside Pike's Music Hall on Fourth Street, with hundreds more milling outside unable to get in, to present documents to the Cincinnati Board of Education, including 2,500 signatures of children and a petition signed by 8,700 adults demanding that the Bible be brought back into the classroom. The morning Cincinnati Gazette's less-than-objective headlines declared, "Bibles in the Schools, A Glorious Demonstration, Immense Audience and Intense Enthusiasm, Rousing Speeches and Ringing Resolutions."

Past Issues

Past Issues